Being able to teach a movement effectively revolves around two main elements: knowledge and communication. As a starting point, a coach should know the movement’s primary points of performance, the musculature involved, potential faults, and corrective strategies for those faults. However, being knowledgeable (or even a great athlete) does not ensure you will be effective at teaching a movement to others, because at the end of the day, coaches need to be able to communicate effectively with their athletes.

A great coach knows how to take their large body of knowledge and distill that down into simple and understandable teaching points, which brings us to our second component of effective teaching: communication. In my own experience as a coach, I have many examples of how I failed to do this.

In the Beginning

In my initial days of coaching, I used a lot of complex terms and would over-explain points of the movement to a level where my athletes were bored, overwhelmed, and confused as to what they were expected to do. As a matter of fact, the first time I taught the push jerk to someone, they left ‚— and never came back again! This helped me realize I needed to change my way of teaching. Simply being knowledgeable about the movement was not enough.

CrossFit Affiliate Summit – CrossFit Advantage – 10/17/2021

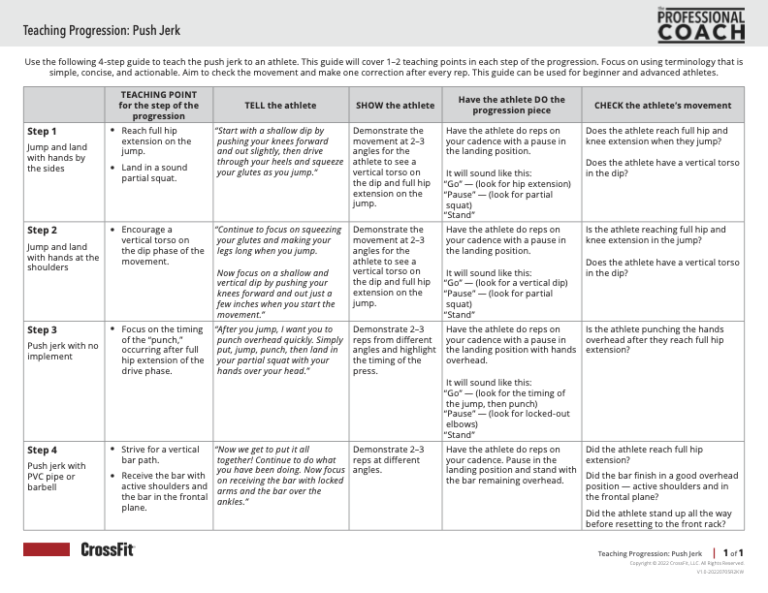

At my CrossFit Level 2 Certificate course, I learned a teaching progression for the push jerk. It involved having athletes start by jumping and landing with their hands by their sides, then jumping and landing with their hands on their shoulders, followed by doing a push jerk with no implement, and finally doing a push jerk with the PVC pipe or empty barbell. I initially scoffed at this progression as it seemed too simple. However, when I gave it a shot with my clients, I was shocked as to how well this progression got them performing the movement.

Finding Success in a Progression

My experience with the push-jerk progression changed the way I started to teach all movements to athletes. I started focusing on creating three- to five-step plans that covered one or two points at a time and progressed to the full movement while using terminology that was simple, concise, and actionable. With each step, I would focus on maintaining a habit of telling athletes what I wanted them to do, demonstrating it, having them do the movement, and then checking their movement to assess mechanics (tell-show-do-check).

Here is a breakdown of this in action with the aforementioned push-jerk progression that includes the important teaching components of each phase of the progression. Print out this sheet and use it as a resource when teaching athletes. You can use this same structure to create a progression to teach any movement.

An added benefit of this type of a progression is that I ended up seeing and correcting movement much more effectively due to having a focus area to watch on each rep. So now my clients were able to move more safely and efficiently. I utilize progressions for nearly every training session I coach regardless of the level of the athlete, as all will benefit from it. Beginners may focus solely on just one or two major points of performance while more experienced athletes can continue to refine nuanced aspects of the movement while warming up the specific musculature involved and range of motion demanded in the upcoming workout. I stuck with the same progressions for months or even years. I strived to dial in my delivery and refine my athletes’ movement every day. Over time, I started challenging myself to teach movements in a different fashion, assessing how effective each method was as well as whether it kept athletes engaged.. The process of creating new progressions is enjoyable to me and a way to keep myself continually learning and growing as a coach.

How to Develop a Progression

The number of reps to perform in each progression piece will vary based upon the size of the class and your ability to engage the group. A general guideline is that you should be able to get eyes on each person at least one time at some point throughout the dynamic phase of the progression. For classes of fewer than 10 people, the goal is to get eyes on each person during the dynamic phase of the full movement.

An effective progression may also require the demand for scaling options to be incorporated for those that cannot complete the entire progression. This will be very common for gymnastics elements. For example, if you are running a kipping pull-up progression, there will likely be a point where some athletes cannot perform the prescribed progression piece. Have scaling options for them to utilize on each step of the progression and list these options in your teaching plans. Do NOT get stuck in a position where you do not have a backup plan for those who need it.

Just as effective CrossFit workouts tend to be simple and elegant, strive to do the same with your teaching plans. The process of developing as a teacher never ends; keep being creative and learn from your mistakes. Embrace the process and have fun!

Comments on I Taught the Push Jerk and They Never Came Back

Eat the elephant one bite at a time by keeping it small and simple.

Thanks, the art of teaching is to be simple and efective. In my Level 2 course we were 5min to teach any moviment, it was be need direct and objective.

I Taught the Push Jerk and They Never Came Back

6