When people who have recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s ask us what they can do to live well, our answer is always exercise. When people who have been living with Parkinson’s for decades ask us what they can do, the answer is the same. Aside from dopamine-replacement medications, exercise is the best medicine you can give a Parkinson’s brain and body because when it comes to a return on investment, the return on physical movement is life-changing.

What Is Parkinson’s?

Parkinson’s is a complex, progressive, and incurable neurodegenerative disease that can affect almost every part of the body, ranging from how a person moves to how they feel, think, and process. It’s a disease that starts very slowly and results in the accumulation of a protein called alpha-synuclein that misfolds within the nerve cells and reduces dopamine-producing nerve cells (neurons) deep inside the brain. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that helps regulate the body’s movement and initiation of movement. Less dopamine in the brain means less control over movement and less mobility in general.

Parkinson’s is second only to Alzheimer’s as the most common aging disorder of the brain and is more common than multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease) combined. Less than 7-8% of cases can be attributed to genetics. Most of the time, people living with Parkinson’s have susceptibility genes that get kick-started by environmental factors, infections, head injuries, and more. That said, there is no single cause of Parkinson’s or predictor of who will get it, and no two people experience Parkinson’s in the same way or along the same timeline — vital information to know as a coach. There’s a common saying in the Parkinson’s community that if you’ve seen one person with Parkinson’s, you’ve seen one person with Parkinson’s. Meaning, it’s very possible that you can work with five Parkinson’s athletes, and all of them will present differently.

While there are clinical scales used to describe stages of Parkinson’s, such as Hoehn and Yahr and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), for the purposes of coaching an athlete with Parkinson’s, we’ll discuss phases most readily observable in the gym.

Prodromal/Pre-motor Parkinson’s

When someone receives a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s, 60-80% of specific dopamine-producing nerve cells are already damaged. And while not usually recognized as symptoms of Parkinson’s at the time, many people can trace their journey back many years to when they first experienced some of the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s, such as loss of smell, depression, constipation, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment, and more.

While as a coach, you are not in the business of diagnosing your athletes, having this knowledge may be helpful as you work with people who have been newly diagnosed and talk about some of the symptoms they experienced long before they received their diagnosis. If you’re lucky enough to travel this journey with an athlete from the pre-motor to the clinical stage, the more you will know about their experience, and the better you will be able to coach them.

Clinical Parkinson’s

The most common way that clinical Parkinson’s is diagnosed is through an exam. In this case, a neurologist or movement disorder specialist (MDS) will run their patient through various movement tests such as finger and toe-tapping, pronation and supination of the hand, the pull test, extremity testing, tremor testing, walking, sit-to-stand, and more. Based on those tests, a specialist can determine whether an individual has two out of the following three cardinal motor symptoms required for a clinical diagnosis:

- Tremor or shaking: A resting tremor, which is specific to Parkinson’s, is when there is trembling in a hand or foot that happens when a person is at rest and typically stops when they are active or moving.

- Bradykinesia: Slowness of movement in the limbs, face, overall body, and/or while walking.

- Rigidity: Stiffness in the arms, legs, or trunk.

Parkinson’s can also be diagnosed via a DaTscan, an imaging test used to help determine a diagnosis when a clinical exam is unclear.

“I Have Parkinson’s. Now What?”

As early as 10 years ago, doctors told people diagnosed with Parkinson’s to rest and take it easy. Now, with the research we have about the value of exercise for people living with Parkinson’s, physicians are sending their newly diagnosed patients out the door with a prescription to exercise.

Working with people who’ve recently received their diagnosis, I usually hear one of the following when they talk about their exercise prescription:

- “I love exercising! Now I have an excuse to spend even more time doing it.”

- “I’m supposed to do what? I’ve never been an exerciser, and now my doctor tells me I need to do it every day — and that it should be intense!”

As you have likely experienced many times, getting started can feel daunting for new people who walk into your affiliate. Now, add the fact that this person just received a diagnosis of an incurable, degenerative disease that primarily impacts movement, and you can add scared, anxious, frustrated, and uncertain to the mix.

Now, imagine during their first moments in the gym, they say to you, “I have Parkinson’s,” and your response is, “You’re in luck. I’ve been digging into the research about Parkinson’s and how valuable exercise is. I can’t wait to work with you.” Imagine seeing their shoulders drop and their eyes perk up. You have the power to change how someone lives with Parkinson’s, and with your help, they can not only live with it, they can thrive with it.

Treatments for Parkinson’s

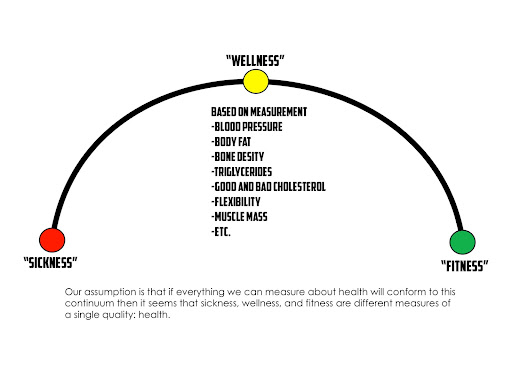

The good news about getting a Parkinson’s diagnosis today is that more treatments exist than ever before. From medications to surgical therapies like deep brain stimulation (DBS), nutrition, exercise, complementary therapies, and more, there are actions people can take every day to live well with Parkinson’s. As a CrossFit coach who has the opportunity to help move them from “sickness” to “fitness” on the sickness-wellness-fitness Continuum, you need to be aware of three primary treatments that impact their daily lives: medication, nutrition, and exercise.

Medication

The gold-standard medication for people with Parkinson’s is Carbidopa/Levodopa (C/L). Dopamine agonists are also very common, especially for people who receive their diagnosis at a young age. While knowing about all types of medication is not essential, knowing how C/L works and what it does for people with Parkinson’s is a great start.

The brain’s circuitry damaged in Parkinson’s is called the basal ganglia. Dr. Cherian Karunapuzha from the Meinders Center for Movement Disorders in Oklahoma City likens the circuits to a switch box that codes for our movements. When the thinking part of the brain decides it needs to do something — like reach out for a dumbbell — the planning part of the brain decides to do this and relays the information to the switch box. The switch box then does two things:

- It switches on all of the relevant programs needed to kickstart the activity.

- It switches off all of the unwanted things that should not be happening while you reach for the dumbbell.

For example, you shouldn’t be tremoring, stiff, slow, or rigid when you reach for the dumbbell. When the switch box is working well, an undamaged brain will quickly switch on and off all of the relevant programs and relay that information back to the part of the thinking brain that channels it down your spinal cord/nerves/muscles, and you act out the movement. In Parkinson’s, that circuitry is damaged and inhibits your ability to switch on all of the relevant motor programs in a timely manner. So, what happens? You still do the movement, but it’s in slow motion. Simultaneously, you also can’t shut off things in a timely manner. As a result, a tremor may start, posture may stoop, balance is compromised, etc.

The unique thing about the circuit that’s being damaged is that the nerves that are operating within the circuit require a particular chemical to crosstalk or communicate. That chemical is dopamine. The problem comes because the nerve shooting out dopamine and the nerve receiving dopamine are differentially damaged. This means the one shooting out dopamine gets damaged first, and the one receiving it gets damaged over time. So if you can somehow introduce dopamine from the outside, the nerve receiving the dopamine can be switched on, allowing you to kickstart the circuit again.

Since C/L is external dopamine, most people living with Parkinson’s take it. What’s important to know is that sometimes it doesn’t work.

When someone starts to experience Parkinson’s motor symptoms, there are usually enough healthy nerves that whatever dose of C/L they take, it keeps recycling it; it reabsorbs back into the nerve and then shoots it out, over and over again. In these early stages, they get a pretty smooth effect. The downside is, as their Parkinson’s progresses, their nerves get more and more damaged, and the worse they get at recycling dopamine. The meds get leaked out more easily, and they experience what is referred to as OFF times. OFF times are when Parkinson’s medications aren’t working optimally, and motor and non-motor symptoms aren’t under control. As Parkinson’s progresses, individuals have to take more and more C/L to manage symptoms, and the window of relief gets shorter and shorter.

It’s important to note that OFF times look different for everyone. For some people with Parkinson’s, OFF means experiencing reduced mobility, increased tremor, muscle cramping, rigidity, slowness, balance issues, stiffness, shortness of breath, and/or swallowing issues. Feeling OFF may also worsen non-motor symptoms and cause fluctuations in cognition, attention, anxiety, depression, and apathy. Being OFF may also cause a person with Parkinson’s to experience increased sweating, lightheadedness, abdominal pain, bloating, urinary issues, visual disturbances, pain, dysesthesia, akathisia, and/or restless legs syndrome.

Many people with Parkinson’s have learned how to time their medication so that when they show up for a ride or exercise class, their meds kick in at the right time to help them get through the workout safely and comfortably. However, OFF times can be unpredictable for various reasons, so while your athlete may be ON the majority of the time, if you see them and their Parkinson’s is more visible than usual, it’s usually because their meds aren’t doing their job. In these cases, it’s important to adapt training to meet them where they are at that moment.

Nutrition

Most people with Parkinson’s have done their fair share of experimenting with different nutritional protocols to see what works best for them and gives them as much symptom relief as possible. And while there’s no reason that someone with Parkinson’s can’t follow CrossFit’s nutritional recommendations, there are a couple of things that are important for you to know if/when the topic of nutrition comes up.

Hydration

Regarding medication, levodopa is not metabolized in the stomach; it’s metabolized in the first part of the intestine. This means anything taken by mouth has to make it to the first part of the intestine to absorb/work. Therefore, people with Parkinson’s should ALWAYS take their medicine with a full glass of water to flush it down. This is not something all doctors tell their people with Parkinson’s, yet it can be the difference between total symptom relief and none. Drinking water also helps with constipation, which is one of the most common and frustrating symptoms of Parkinson’s. Encourage your athletes to bring water to workouts and to drink throughout.

Protein

Since eating adequate amounts of protein to build lean muscle mass is a key part of CrossFit’s nutritional recommendation, it’s important to know that protein interferes with the absorption of levodopa. The amino acids from protein look very similar to levodopa as viewed by the gut. Since the gut has specific channels through which amino acids can be transferred, if your athlete eats a burger patty and then takes their levodopa, their gut can’t filter everything through the gates to the intestine, leading to interference in the absorption of levodopa. This lack of absorption of levodopa can lead to OFF times in many since the protein essentially blocks their meds. Therefore, the best practice for people with Parkinson’s who take C/L is to eat one hour before taking their medications or two hours after taking them, especially regarding protein.

Exercise

Why People With Parkinson’s MUST Exercise

As mentioned earlier, people newly diagnosed with Parkinson’s used to be told to rest and take it easy. Today, if they have doctors who truly understand the disease, they’re told the exact opposite: exercise daily, intensely, and as often as possible. And, if you can, do it with others.

For people with Parkinson’s, regular exercise can:

- Improve mobility and coordination

- Boost mood

- Reduce stiffness and tremor

- Minimize soreness and fatigue

- Improve cognitive function

- Improve gait and balance

- Reduce sleep problems

- Reduce postural instability

- Provide a critical social outlet

And it may even slow down the progression of Parkinson’s itself.

“The adverse effects of inactivity include cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, insomnia, cognitive decline, depression, constipation, and all lead to early mortality. All of these are risk factors when you have Parkinson’s, so if you are both inactive and have Parkinson’s, your risk of early mortality is higher.” – Professor Bas Bloem, Medical Director and Neurologist at the Parkinson Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

The recommended guideline for people with Parkinson’s to experience the benefits of exercise is to engage in a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week or 75 minutes if it’s high-intensity exercise. That said, here are a few things to keep in mind for your Parkinson’s athletes:

- Something is always better than nothing. If they come into the gym but are feeling OFF, are moving slowly, and didn’t sleep the night before, any movement they do for that hour is a victory.

- High-intensity exercise (or ~80% of max heart rate) is better than slow and low. When it’s safe for them to do so, they will get more bang for their buck as the intensity rises.

- They will likely reach the “too much exercise” threshold before their non-Parkinson’s peers will. The worst thing that can happen to someone with Parkinson’s is they get too tired or too hurt to exercise. Challenge them to reach their volume, intensity, and strength goals but work with them to reach the level that’s optimal for the day they’re having.

Based on these recommendations and the fact that endurance, strength, intensity, and balance are critical domains for people with Parkinson’s to concentrate on to help with their motor and non-motor symptoms, CrossFit can be magic.

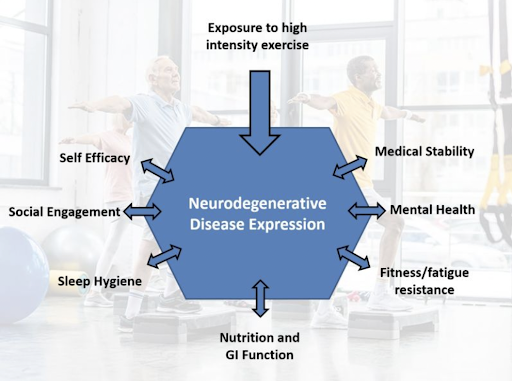

Image courtesy of Mike Studer, DPT

Evaluation

One thing we encourage all people with Parkinson’s to do as soon as they receive a clinical diagnosis is to be evaluated by a physical therapist or trainer, ideally one who specializes in working with people with movement disorders. While many recently diagnosed people don’t think they “need” it, the value of therapeutic evaluation from the beginning is considerable. By working with a physical therapist or CrossFit coach who understands Parkinson’s and its progression, a person gets feedback immediately when they start to go slightly downhill, and their coach can kickstart and motivate them to push Parkinson’s complications as far down the road as possible. For this reason, having some benchmarks that you test and retest with your Parkinson’s athletes can provide excellent information on their fitness gains and the state of their Parkinson’s progression.

Neuroplasticity

According to Mike Studer, a physical therapist who specializes in working with people with Parkinson’s, the main reason for prescribing exercise for people with Parkinson’s is so they can take action to slow the disease process, preserve what they have, and make connections that are often left off the table because of learned nonuse.

Learned nonuse happens when a person gets a diagnosis of Parkinson’s, and because of the stories they start telling themselves, they stop engaging in life. They stop taking 10,000+ steps daily, climbing stairs, trying to balance without a walker, etc. They deem themselves “sick” or incapable, and pretty soon, they are. If they don’t challenge those facets of endurance, strength, and balance, neuroplasticity is left on the table for a coach like you to tap into.

Along similar lines, one of the best reasons for people with Parkinson’s to do CrossFit is because it’s possible to build redundancies or a reserve. Think about the athletes in your affiliate. It’s 6:30 a.m., and someone just signed in for their first CrossFit class. This athlete competed as a gymnast for many years but hasn’t stepped on a gym floor in ages. Next to them is an athlete who also just signed in for their first class, but they have a very limited athletic background. The person who did gymnastics for 10 years has a higher water table to start with than the one who didn’t, and therefore, it will take them less time to see gains from doing CrossFit. The same is true for people living with Parkinson’s. The more you can help them to build endurance, strength, and balance early on, the higher their water table will be and the more they will have to pull from as their Parkinson’s progresses.

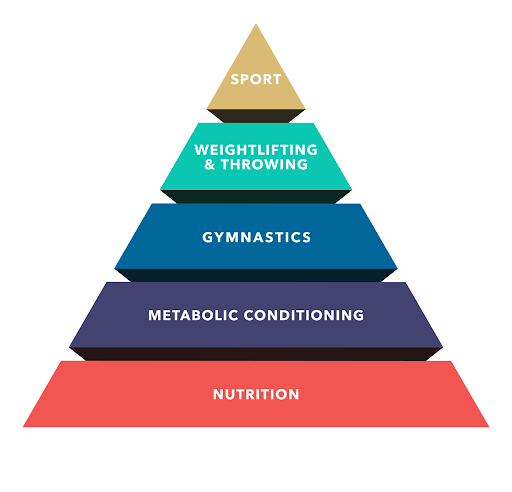

As a coach, you can drive home the point that going to CrossFit is an investment that has the power to pay off in the form of many more years of thriving with Parkinson’s instead of barely getting by. The more time and energy they put into metabolic conditioning, gymnastics, weightlifting, and sport now, the more they will have in the bank when it’s time to withdraw. If there’s nothing in the bank when that happens, the decline will be much more precipitous.

Falling, Exercise, and Parkinson’s

The most common reason people with Parkinson’s are admitted to the hospital is due to falls.

Falls are a significant cause of disability, loss of independence, and reduced quality of life for people with Parkinson’s. Approximately 45-65% of people with Parkinson’s fall annually, and 50-85% fall regularly. Falling can lead to fear of falling, which limits their desire to be active and impacts their ability to mitigate symptoms with exercise, restricting activities of daily living (ADLs), resulting in learned nonuse, and higher levels of injuries.

Think about all of the things we draw on in those split seconds before a fall:

- Reaction speed

- Cognitive processing ability

- Flexibility

- Pain-free range of motion

- Strength to stop your body’s momentum

- Power – generating force fast

The good news is that every exercise aspect of the fitness pyramid (metabolic conditioning, gymnastics, weightlifting, sport) addresses the above and can play a role in helping prevent falls or make them less severe when they do happen.

Metabolic Conditioning

In 2003, on a bike ride with a friend, Dr. Jay Alberts from the Cleveland Clinic noticed something that would go on to shape the next two decades of his life. During the multi-day group ride across Iowa (RAGBRAI), Dr. Alberts pedaled a tandem bike with a friend with Parkinson’s and noticed that after a few days, his friend’s handwriting and manual dexterity dramatically improved.

In 2012, Alberts led the research for the clinical trial called CYCLE and found that an eight-week high-intensity aerobic exercise program markedly enhances overall motor function, certain aspects of walking, and cognitive function in people with Parkinson’s.

In 2012, Alberts led the research for the clinical trial called CYCLE and found that an eight-week high-intensity aerobic exercise program markedly enhances overall motor function, certain aspects of walking, and cognitive function in people with Parkinson’s.

Since this discovery, Dr. Alberts and many others have dedicated their careers to studying the effects of exercise, especially high-intensity exercise, on motor and non-motor performance. The research continually supports the belief that forced and high-intensity aerobic exercise improves motor function (and more) in people with Parkinson’s.

But, of course, there’s still more to the story. Currently, the SPARX3 study is the first randomized control trial designed to investigate the effects of moderate- and high-intensity aerobic exercise on disease progression in people with Parkinson’s who have yet to begin medication. The more you know about this research, the better coach you’ll be to your Parkinson’s athletes.

Gymnastics

As one of the three foundational modalities of CrossFit, the ability to perform gymnastics movements can have a dramatic effect on fitness and how well a person lives with Parkinson’s. Gymnastics helps people develop coordination, agility, balance, and accuracy — all aspects that influence someone’s ability to limit falls or limit the consequences if they do fall. The other great thing about gymnastics for someone with Parkinson’s is that there’s a low barrier to entry. Everyone has a body, and they can make significant gains by just learning how to move their body better, more efficiently, and with better control. So, while the fitness pyramid hierarchy reflects a belief that one should develop cardiovascular efficiency first, when working with someone with Parkinson’s who is new to exercise and may be anxious about and uncomfortable with the intensity that comes with metabolic conditioning, or who has motor symptoms that make it difficult for them to run, ride, row, etc., working on gymnastics might be a good doorway into everything else on the pyramid. And, if you can help them develop the strength, agility, balance, and accuracy it takes to prevent falls via gymnastics movements, you may become their coach for life.

Weightlifting

While much of the research on exercise and Parkinson’s has focused on high-intensity and aerobic training, more and more researchers are working to investigate the value of strength training for those with Parkinson’s. That said, even without much research on it for this particular population, we know that it’s critical for people with Parkinson’s to have strong muscles. When you have strong muscles at the joints, arms swing higher and legs take bigger steps, which can significantly help those who struggle with shuffling or freezing of gait (FOG), very common symptoms of Parkinson’s that lead to falls. Additionally, upper- and lower-body muscles are the same ones we use when we fall or stop a fall. If our muscles aren’t strong enough, it’s challenging to steady our gait or brace for a fall. Strong muscles help compensate for Parkinson’s.

Sport

Sport lives at the top of the fitness pyramid in CrossFit because it’s the application of everything that comes before it on the pyramid. And unlike a typical training session in the gym, sport requires us to express the skills we learn and develop in the gym in more natural ways.

What is the value of sport to people living with Parkinson’s? It’s pretty simple. When someone with Parkinson’s leaves the gym, they enter into the sport of Parkinson’s, which requires them to combine all 10 general physical skills of CrossFit to get through their day. Like sport, Parkinson’s involves varied and unpredictable movements. It requires athletes to turn on a dime, navigate obstacles, and call on their aerobic, anaerobic, strength, and balance capacities all the time. Of course, people with Parkinson’s play sports, too, but when it comes to GPP, their life is a sport.

Tips on Coaching a Person With Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s is a complicated disease. As a coach, knowing the following will make you stand out and keep them coming back for more:

- The person you saw on Monday will be worse on Friday, even if it doesn’t look like it. Don’t mistake them being ON for being better or their Parkinson’s reversing.

- Sleep disturbances are one of the most common and frustrating symptoms of Parkinson’s. Lack of sleep or sleep disturbances can impact their training in meaningful ways. But showing up even when they’re tired will, too.

- Medications don’t always work. Sometimes they are delayed, sometimes they never kick in, and sometimes, especially as Parkinson’s progresses, their window of effectiveness diminishes. Be open to adjusting your plan and talking to your athletes about it.

- Facial masking is one of the symptoms of Parkinson’s many people don’t know about, but it’s critical as a coach that you do. Just like their body often becomes slow and rigid, they lose the ability to have facial expressions. When this happens, it may look to you like they are not interested, unhappy, or not tracking what you’re saying. The other possibility is that their Parkinson’s isn’t allowing them to match their insides with their outsides. Learn to listen to their words sometimes rather than their face.

- Soft and slow speech. This is similar to facial masking in that people with Parkinson’s will start to experience soft and slow speech and often don’t realize it. If you have trouble hearing them, move to a quieter spot in the gym. If their speech is slow, give them time. The thoughts are there. They just aren’t able to communicate as quickly anymore.

- Constipation is common and monumentally frustrating for most. On the one hand, it can make people not want to work out. On the other, it’s often precisely what they need to get things moving. Please encourage your Parkinson’s athletes to drink water and move every chance they get.

- Freezing of gait (FOG) often happens in crowded, chaotic, and new environments. Before working with someone with Parkinson’s, ask them if they experience FOG and then make a plan that will allow them to enter and move safely about the gym.

- Cognitive impairment is a common non-motor symptom of Parkinson’s because, in the same way that Parkinson’s slows down physical movement, it slows down the ability to think and process information. Fortunately, research shows that exercise improves cognition and is one of the best things you can do to reduce the risk of getting Parkinson’s disease dementia. The more cognitive tasks someone with Parkinson’s can do in the gym (think Turkish get-up), the better.

- nOH, neurogenic orthostatic hypotension, is caused by the failure of the autonomic nervous system to regulate blood pressure in response to postural changes. Approximately 30-50% of people with Parkinson’s have nOH, so it’s important to understand it. It often presents as dizziness, lightheadedness, near fainting, or fainting when moving from lying down to sitting or sitting to standing. It’s a good idea to talk to your Parkinson’s athlete about this so you can keep an eye on them or modify when you have a transition in a workout, such as moving from AbMat sit-ups to push presses.

- Dyskinesia, next to resting tremor, is probably the most visible sign that someone has Parkinson’s. It’s often described as uncontrolled jerking, dance-like, or wriggling movements. In people with Parkinson’s, it is most often associated with the long-term use of levodopa. Research shows that exercise substantially improves levodopa-induced dyskinesia and other motor symptoms in some people. However, for others, the exact opposite is true. Here are some reasons exercise may worsen dyskinesia and what to do about it.

- The impact Parkinson’s has on emotions and mood is often overlooked because it is complicated and harder to talk about objectively than physical symptoms. But approximately 50-60% of people living with Parkinson’s experience varying levels of depression and anxiety, so chances are good that you will notice these symptoms in your athletes. Fortunately, exercise is great medicine for reducing both.

- When most people are diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it feels as though everything they imagined and planned for their life is out the window. And over time, this grief and sense of loss can turn to feelings of demoralization, lack of relevance, and lack of confidence. CrossFit has the power to change that and restore a sense of self-efficacy in these athletes. Remember this when you are working with them. Help them establish goals that are attainable but not so far from what the non-Parkinson’s athletes are doing that they feel separate. Help them celebrate their victories. While Parkinson’s does not get better and no amount of exercise can reverse it, achieving goals in the gym is very possible and a way for them to experience the kind of progression that’s empowering.

- While you will likely encounter people with Parkinson’s who show little to no signs of having it, for the most part, Parkinson’s is visible. People shake, tremor, freeze, shuffle, and more. For some, this vulnerability is too much, and they choose to isolate themselves. The problem with disconnecting is that social isolation can exacerbate symptoms, put them at risk for developing other health problems, increase their chances of experiencing depression, accelerate cognitive decline, and decrease their quality of life. This is why the CrossFit community can be literal medicine for people with Parkinson’s. As their coach, create as many opportunities as you can for them to connect with your community, get involved at your affiliate, and serve as inspiration for your members. Not a day goes by that I don’t hear from someone in our Parkinson’s community about how important their community connections are for living well. By welcoming them to your gym, showing them they belong by learning what you can about Parkinson’s, and creating opportunities for them to connect and bond with others, you can help push their progression down the road and help them live better than they ever thought they could with Parkinson’s.

The Call to Action

Over time, I’ve come to see CrossFit as BDNF for people with Parkinson’s. BDNF, or brain-derived neurotrophic factor, is essentially fertilizer for the brain. Grass can still grow to some extent without fertilizer, but if you don’t have good soil and enough rain, aka fitness, the grass will steadily decay. CrossFit/BDNF helps to enrich the soil of those living with Parkinson’s. When they have neurologically stimulating experiences like CrossFit, their brains and bodies will be fed, work better, and stay healthier longer.

As a coach, you know how important it is to meet each athlete where they are. If you start working with a Parkinson’s athlete who is early on in their diagnosis and is super competitive, you might already know where to start. If you start working with a Parkinson’s athlete who is not competitive and is nervous or scared about working out, learn how to frame their expression of wellness.

With a competitive person who has done a lot of exercise in their life for the pure joy and love of it, lean into it. Use phrases like Rx’d, personal best, for time, etc. For someone with whom that’s not the case, use language that is more about being functional:

- “Think of how much easier getting in and out of the car will be.”

- “This will help you be less scared walking to the store because your strength and balance will be much better.”

- “When you’re cleaning that wall ball, think about how much easier it will be to lift your grandson when you’re not shaking or off balance.”

- “Think of how much these air squats will help you get up and down while planting in your garden.”

Frame the language around their goals to keep them coming back so they, too, can become believers in the magic of CrossFit and live well with Parkinson’s today and for many years to come.

Parkinson’s and the Aging Athlete

Since Parkinson’s is a disease of aging, if you want to learn even more about how to coach this population in your gym, register for Coaching the Aging Athlete. You will learn practical methods for applying CrossFit to an aging population, taking into account how age, fitness, goals, and injury state interact to create different coaching challenges and scenarios.