The benefit of preventive drugs such as statins is often quantified as the NNT — the number needed to treat (1). The NNT reflects the number of subjects who would need to be given a drug for one negative clinical event to be prevented — for example, an NNT of 40 for a statin preventing cardiovascular death suggests that for every 40 patients given the statin, one cardiovascular death will be prevented.

This number, however, distorts the likely reality of the benefit distribution. This “lottery” model suggests a single subject receives the entire benefit — in the example above, preventing a cardiovascular death that otherwise would have occurred — while other subjects receive no benefit. It is more likely that most or even all subjects receive some benefit from the drug, and the fact that we could only observe this benefit in one in 40 patients (to continue the above example) is an artifact of a clinical trial that observes a fixed group of subjects over a fixed period of time.

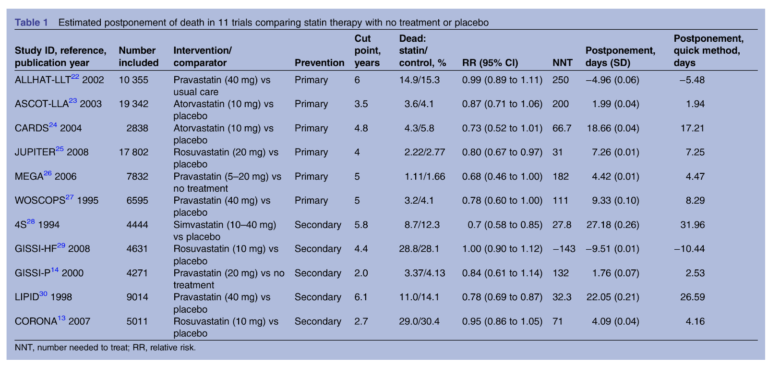

This 2014 review aimed to quantify the clinical impact of statins differently, assessing the mean extension of life due to statin treatment. The review authors pulled data from 11 randomized clinical trials comparing mortality in subjects taking statins to those who did not. Six trials tested statins for primary prevention — that is, in subjects who had not yet had a heart attack — while five tested the effectiveness of statins in preventing a second heart attack. By comparing the survival curves (which graph mortality rates over time) between subjects who received statins and those who did not, researchers could estimate how long statins were extending life in the former compared to the latter.

The results are summarized in the chart below. The most positive primary prevention trial found statins increased life expectancy by 19 days; in secondary prevention, the greatest observed effect was 27 days. The median benefit associated with statin use was 3.2 days in primary prevention and 4.1 days in secondary prevention. In other words, statins extended life expectancy by less than a week.

The authors note these results may underestimate the benefits of statins in some subjects — it is possible, for example, that some share of subjects receive a larger benefit from statin use and some subjects receive no benefit — but the data suggests statins have little effect on mortality on a population scale.

Separate research suggests if the benefits of statins were explained this way, the majority of subjects would not choose to take them (2). This research suggests, at minimum, that subjects who experience statin-related side effects may not need to continue treatment, as the magnitude of benefit is likely small. More broadly, it suggests the mean benefits of statins are sufficiently small that these benefits ought to be carefully considered against the risks and costs before blanket prescriptions are made.

The Effect of Statins on Average Survival in Randomised Trials, An Analysis of End Point Postponement