An infamous sales tool of shady retail outlets called “bait and switch” lures customers in with the offer of a deal so good they can’t resist, and once they’ve taken the bait, switches the item in question to a higher-priced alternative. It’s an age-old trick of double-dealing, but it isn’t limited to cheap furniture outlets. It’s also a sleight of hand employed in scientific research.

Moving the Goal Posts

Take, for example, the issue of the lipid hypothesis, dating back to the original Framingham Study. At the outset, no one had a clue about what was actually causing heart disease, and scientists rightly attempted to determine what the cause or causes might be—answering such questions is what science is supposed to do, after all. Cholesterol was investigated as a culprit in part because it seemed like it might play a role; there was cholesterol in the plaque found in diseased coronary arteries, and it was something quantifiable. But despite their best efforts, researchers could find no significant connection between cholesterol and cardiac disease other than an association between the two, which, of course, does not prove causality.

Even then, the data cast doubt on the hypothesis that cholesterol is the culprit behind heart disease. Nevertheless, the myth took hold and the decades-long quest to prevent and cure cardiovascular diseases through aggressive cholesterol lowering began. It’s important to note here that the endpoint being sought from the outset was a reduction in disability and deaths from heart disease.

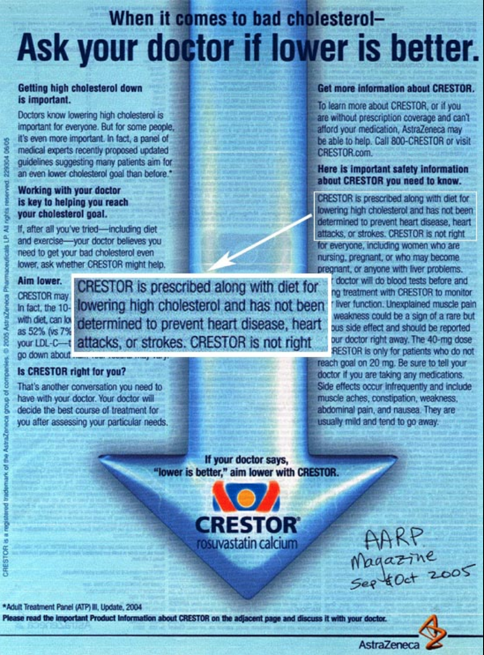

Cue the discovery of statins, which act to inhibit the body’s rate-limiting step in the cholesterol production pathway: HMG-coenzyme-A reductase. Early studies proved the drugs did their enzyme-inhibiting job and indeed lowered cholesterol, but the studies failed to show that such lowering actually significantly reduced risk of death from heart disease. When there was a very slight reduction in heart disease mortality, the studies also failed to reveal a reduction in all-cause mortality—meaning that maybe people weren’t dying of heart attacks but more often of something else. All the same, they reached an unfavorable endpoint. And this was widely known. Notice the magnified text inside the white box in this ad from 2005:

-

Figure 1

But this knowledge didn’t dissuade marketers from promoting the drugs anyway. Like any good used-car salesman, they whipped out the bait and switch and shifted the desired endpoint from suffering or dying from a heart attack to cholesterol reduction. Having spent a truckload of money promoting the idea that cholesterol was the root cause of heart disease (which, of course, was not the case), they could now switch the desired outcome from “prevents heart attack and stroke” to “lowers cholesterol,” touting a benefit that had, in the minds of the public, become synonymous with reducing the risk of dying from a heart attack.

The Infamous P-Value Hack

Another bait-and-switch maneuver is the technique called p-value hacking. Because of the (perhaps unjust) preeminence modern research gives results that achieve statistical significance, and the likelihood of a paper’s not being published in a peer-reviewed journal if the results do not, researchers sometimes move the goal posts by chasing p-values. They lay out their hypothesis, design their protocols, declare which outcome measures they seek to validate, and collect the data. Then, after the fact, if what they were originally studying doesn’t pan out, they put things in reverse, slice and dice the data, see what in hindsight might reach that magic p<0.05 number, and — voilá — the goal posts move.

P-value hacking has become notorious, with reputable journals and careful readers ever on the lookout for it. Fortunately, at least in recent years, the supposed requirement that outcome measures be stated clearly at the time a study is registered on clinicaltrials.gov has cut down on its use, at least as it applies to drug studies. But that only covers the last 8 or 9 years, and there’s a tsunami of research that predates those requirements.

Falsus in Uno, Falsus in Omnibus

Honesty and integrity are requisite foundations of credible scientific study. Without them, neither the learned colleague nor inquisitive layman can hope to sort fact from fiction or truth from prevarication. How else can we know what to believe? In the House of Science, transparency and accuracy must rule; there’s simply no place for intellectual chicanery, such as the cardinal sin of baiting and switching. The Latin dictum falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus (false in one thing, false in everything) sums up why even a few such shenanigans corrupt scientific research.

Additional Reading

- The Cardinal Sins of Skewed Research, Part 1: Cloaking

- The Cardinal Sins of Skewed Research, Part 2: Racking

- The Cardinal Sins of Skewed Research, Part 3: Sweeping

- The Cardinal Sins of Skewed Research, Part 5: Burning Britches

Drs. Michael and Mary Dan Eades are the authors of 14 books in the fields of health, nutrition, and exercise, including the bestseller Protein Power.

Dr. Michael Eades was born in Springfield, Missouri, and educated in Missouri, Michigan, and California. He received his undergraduate degree in engineering from California State Polytechnic University and his medical degree from the University of Arkansas. After completing his medical and post-graduate training, he and his wife, Mary Dan, founded Medi-Stat Medical Clinics, a chain of ambulatory out-patient family care clinics in central Arkansas. Since 1986, Dr. Michael Eades has been in the full-time practice of bariatric, nutritional, and metabolic medicine.

Dr. Mary Dan Eades was born in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and received her undergraduate degree in biology and chemistry from the University of Arkansas, graduating magna cum laude. After completing her medical degree at the University of Arkansas, she and her husband have been in private practice devoting their clinical time exclusively to bariatric and nutritional medicine, gaining first-hand experience treating over 6,000 people suffering from high blood pressure, diabetes, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides, and obesity with their nutritional regimen.

Together, the Eades give numerous lectures to the general public and various lay organizations on their methods of treatment. They have both been guest nutritional experts on over 150 radio and television shows, including national segments for FOX and CBS.

Comments on The Cardinal Sins of Skewed Research, Part 4: Bait and Switch

The Latin dictum falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus (false in one thing, false in everything) sums up this section. In order for a hypothesis to be right and become a theory you can't have one study that proves it doesn't work. It is not a matter of finding a possibility that it could be true. It is about knowing it can't be false. There is this sens of it dosesn't matter if a lot of studies can't be reproduced, or don't show the correlation we will just keep going until we prove what we want (especially if it sells our product). That is not science.

Good read, starting on part 4 makes me want to go back and read the first 3 parts!

The Cardinal Sins of Skewed Research, Part 4: Bait and Switch

2