Excerpt and summary courtesy of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group:

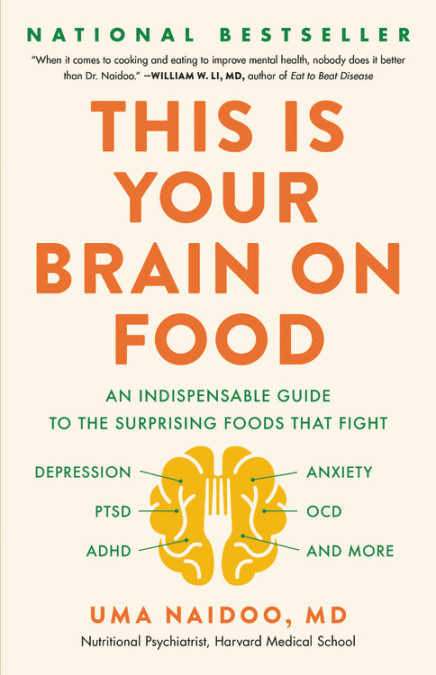

Eat for your mental health and learn the fascinating science behind nutrition with this “must-read” guide from an expert psychiatrist (Amy Myers, MD).

Did you know that blueberries can help you cope with the after-effects of trauma? That salami can cause depression, or that boosting Vitamin D intake can help treat anxiety?

When it comes to diet, most people’s concerns involve weight loss, fitness, cardiac health, and longevity. But what we eat affects more than our bodies; it also affects our brains. And recent studies have shown that diet can have a profound impact on mental health conditions ranging from ADHD to depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, OCD, dementia and beyond.

A triple threat in the food space, Dr. Uma Naidoo is a board-certified psychiatrist, nutrition specialist, and professionally trained chef. In This Is Your Brain on Food, she draws on cutting-edge research to explain the many ways in which food contributes to our mental health, and shows how a sound diet can help treat and prevent a wide range of psychological and cognitive health issues.

Packed with fascinating science, actionable nutritional recommendations, and delicious, brain-healthy recipes, This Is Your Brain on Food is the go-to guide to optimizing your mental health with food.

Note: CrossFit has no conflicts of interest or financial interests to report in association with the sale of this book.

Chapter 1: The Gut-Brain Romance

There aren’t many things that keep me up at night. I like my sleep. But on occasion, I find myself tossing and turning because I think that in psychiatry, and in medicine as a whole, we have completely missed the forest for the trees.

Granted, we’ve come a long way from the cold showers and shackles of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In those early barbaric years, “madness” was considered a sinful state, and the mentally ill were housed in prisons. As civilization progressed, mentally ill patients were moved to hospitals (1). The problem is, as we became more and more focused on the troublesome thoughts and emotions of mental illnesses, we stopped noticing that the rest of the body was also involved.

This wasn’t always the case. In 2018, historian Ian Miller pointed out that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century doctors were clued in to the fact that the body’s systems are connected (2). That’s why they talked about the “nervous sympathy” among our different organs.

However, in the late nineteenth century, doctors changed this perspective. As medicine became more specialized, we lost track of the big picture, only looking at single organs to determine what was wrong and what needed fixing.

Of course, doctors did recognize that cancers might spread from

THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON FOOD

one organ to the next, and that autoimmune conditions like sys- temic lupus erythematosus could affect multiple organs in the body. But they neglected to see that organs that were seemingly quite separate in the body might still profoundly influence one another. Metaphorically speaking, illness could come from a mile away!

Compounding the problem was that, rather than working collaboratively, physicians, anatomists, physiologists, surgeons, and psychologists competed with one another. As one British doctor wrote in 1956, “There is such a clamour of contestants for cure that the patient who really wants to know is deafened rather than enlightened” (3).

This attitude prevails in medicine even today. That’s why so many people are oblivious to the fact that when mental health is affected, the root of the problem is not solely in the brain. Instead, it’s a signal that one or more of the body’s connections with the brain has gone awry.

We know that these connections are quite real. Depression can affect the heart. Pathologies of the adrenal gland can throw you into a panic. Infections darting through your bloodstream can make you seem like you have lost your mind. Maladies of the body frequently manifest as turbulence of the mind.

But while medical illness can cause psychiatric symptoms, we now know that the story goes even deeper. Subtle changes in distant parts of the body can change the brain too. The most profound of these distant relationships is between the brain and the gut. Centuries ago, Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, recognized this connection, warning us that “bad digestion is the root of all evil” and that “death sits in the bowels.” Now we are figuring out how right he was. Though we are still on the forefront of discovery, in recent years the gut-brain connection has provided one of the richest, most fertile research areas in medical science and the fascinating nexus of the field of nutritional psychiatry.

ONCE UPON A TIME . . .

Watching a developing embryo differentiate is like looking through a kaleidoscope.

Once upon a time, a sperm made its way to an egg. They were not ships passing in the night. They connected. And when the union was successful, you were conceived. Warmly ensconced in your mother’s uterus, you, as this fertilized egg (called a zygote), started to change.

At first, the zygote’s smooth outer surface developed ripples like a mulberry. As time went on, the magical egg, under the spell of biological instructions, started to change its configuration until your baby body took shape. Eventually, after nine long months, you were armed with a heart, gut, lungs, brain, limbs, and other nifty things, ready to announce yourself to life.

But before all that, before you emerged ready to take on the world, before your gut and brain became distinct entities, they were one. They came from the same fertilized egg that gave rise to all the organs in your body.

In fact, the central nervous system, made up of the brain and spinal cord, is formed by special cells known as neural crest cells. These cells migrate extensively throughout the developing embryo, forming the enteric nervous system in the gut. The enteric nervous system contains between 100 million and 500 million neurons, the largest collection of nerve cells in the body. That’s why some people call the gut “the second brain.” And it’s why the gut and brain influence each other so profoundly. Separate though they may appear to be, their origins are the same.

LONG-DISTANCE RELATIONSHIP

I once had a patient who was confused as to why I talked about her gut while treating her mind. To her, it seemed irrelevant. “After all,” she said, “it’s not like they are actually next to each other.”

While your gut and brain are housed in different parts of your body, they maintain more than just a historical connection. They remain physically connected too.

The vagus nerve, also known as the “wanderer nerve,” originates in the brain stem and travels all the way to the gut, connect- ing the gut to the central nervous system. When it reaches the gut, it untangles itself to form little threads that wrap the entire gut in an unruly covering that looks like an intricately knitted sweater. Because the vagus nerve penetrates the gut wall, it plays an essential role in the digestion of food, but its key function is to ensure that nerve signals can travel back and forth between the gut and the brain, carrying vital information between them. Signals between the gut and brain travel in both directions, making the brain and gut lifelong partners. That is the basis of the gut-brain romance.

CHEMICAL ATTRACTION

So how does your body actually transmit messages between the gut and the brain via the vagus nerve? It’s easy enough to imagine the gut and the brain “talking” to each other over some kind of biologi- cal cell phone, but that doesn’t quite do justice to the elegance and complexity of your body’s communication system.

The basis of all body communications is chemical. When you take a pill for a headache, you usually swallow it, right? It enters your mouth, then makes its way to your gut, where it is broken down. The chemicals from the pill travel from your gut to your brain through your bloodstream. And in your brain, they can decrease the inflammation and loosen your tense blood vessels too. When the chemicals you swallow successfully exert their effects on the brain, you feel relief from that pain.

In the same way as the chemicals in that pill, chemicals produced by the gut can also reach your brain. And chemicals produced by your brain can reach your gut. It’s a two-way street.

In the brain, these chemicals originate from the primary parts of your nervous system (with an assist from your endocrine system): the central nervous system, which comprises the brain and spinal cord; the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which comprises the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems; and the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA-axis), which comprises the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal gland.

The central nervous system produces chemicals such as dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine that are critical for regulating mood and processing thought and emotion. Serotonin, a key chemical deficient in the brains of depressed and anxious people, plays a major role in regulating the gut-brain axis. Serotonin is one of the most buzzed-about brain chemicals because of its role in mood and emotion, but did you know that more than 90 percent of serotonin receptors are found in the gut? In fact, some researchers believe that the brain-serotonin deficit is heavily influenced by the gut, an idea we’ll dig deeper into later on.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is in charge of a broad range of essential functions, most of which are involuntary: your heart keeps beating, and you keep breathing and digesting food because of your ANS. When your pupils dilate to take in more light in a dark room, that’s the ANS. Perhaps most crucially for our purposes, when your body is under duress, your ANS controls your fight-or-flight response, an instinctual reaction to threat that sends a cascade of hormonal and physiological responses through your body in dangerous or life-threatening situations. As we’ll see later on, the gut has a profound effect on fight or flight, particularly through the regulation of the hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline (also known as epinephrine and norepinephrine).

The HPA-axis is another crucial part of the body’s stress machine. It produces hormones that stimulate release of cortisol, the “stress hormone.” Cortisol amps the body up to handle stress, providing a flood of extra energy to deal with difficult situations. Once the threat passes, the cortisol level returns to normal. The gut also plays an important role in cortisol release and is instrumental in making sure the body responds to stress effectively.

In a healthy body, all these brain chemicals ensure that the gut and brain work smoothly together. Of course, as in all delicate systems, things can go wrong. When chemical over- or underproduction disrupts this connection, the gut-brain balance is thrown into disarray. Levels of important chemicals go out of whack. Moods are upset. Concentration is disrupted. Immunity drops. The gut’s protective barrier is compromised, and metabolites and chemicals that should be kept out of the brain reach the brain and wreak havoc. Over and over again throughout this book, we are going to see how this chemical chaos gives rise to psychiatric symptoms, from depression and anxiety to loss of libido to devastating conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

In order to correct those chemical imbalances and restore order to brain and body, you might assume that we would need a barrage of sophisticated, carefully engineered pharmaceuticals. And to a degree, you’d be right! Most drugs used to treat mental conditions do seek to alter these chemicals to return the brain to a healthy state — for example, you may have heard of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (most commonly referred to as SSRIs), which boost serotonin in order to fight depression. Modern mental health medications can be a godsend to patients who struggle with a variety of disorders, and I don’t want to downplay their importance as a therapy in many circumstances.

But what sometimes gets lost in discussions about mental health is a simple truth: the food you eat can have just as profound an effect on your brain as the drugs you take. How can something as basic and natural as eating be as potent as a drug that cost millions of dollars to develop and test? The first part of the answer lies in bacteria.

WHY SMALL THINGS MATTER

Behind the scenes of the gut-brain romance is a huge collection of microorganisms that reside in the gut (4). We call this panoply of different bacterial species the microbiome. The gut microbiome — in both humans and other animals — is another type of romance, with both parties relying on each other for survival. Our guts provide the bacteria with a place to live and thrive, and in return they perform crucial tasks for us that our bodies can’t perform on their own.

The microbiome is made up of many different types of bacteria, with a much greater diversity of species in the gut than anywhere else in the body. Each individual gut can contain up to a thousand different species of bacteria, though most of them belong to two groups — Firmicutes and Bacteroides — which make up about 75 percent of the entire microbiome.

While we won’t spend too much time discussing individual species in this book, suffice it to say that when it comes to bacteria, there are good guys and bad guys. The microorganisms that inhabit the gut are normally good guys, but it’s inevitable that some bad ones get mixed in. This isn’t necessarily a concern, as your body generally makes sure that the good and bad bacteria stay at the right balance. But if diet, stress, or other mental or physical problems cause changes in gut bacteria, that can cause a ripple effect that leads to many negative health effects.

The idea that the microbiome plays such an essential role in bodily function is relatively new in medicine (think about how often you’ve heard of bacteria as “germs that will make you sick” rather than as a helpful team of microorganisms that performs a vital service), particularly when it comes to bacteria’s influence on the brain. But over the years, the science has been building that gut bacteria can affect mental function.

About thirty years ago, in one of the most compelling studies that first made us aware that changes in gut bacteria could influence mental function, researchers reported on a series of patients with a kind of delirium (called hepatic encephalopathy) due to liver failure. In hepatic encephalopathy, bacterial “bad guys” produce toxins, and the study showed that these patients stopped being delirious when antibiotics were administered by mouth. That was a clear sign that changing gut bacteria could also change mental function.

In the years since, we’ve accumulated a huge amount of knowledge about how the gut microbiome affects mental health, and we’ll unpack that knowledge throughout this book. For instance, did you know that functional bowel disorders like irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease also come with mood changes due to bacterial populations being altered (5)? Or that some clinicians feel that adding a probiotic as part of a psychiatric medication treatment plan can also help to lower anxiety and depression? Or that if you transfer the gut bacteria of schizophrenic humans into the guts of lab mice, those mice also start to show symptoms of schizophrenia?

The primary reason gut bacteria have such a profound effect on mental health is that they are responsible for making many of the brain chemicals we discussed in the last section. If normal gut bacteria are not present, production of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, glutamate, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) — all critically important for the regulation of mood, memory, and attention— is impacted. As we’ll see, many psychiatric disorders are rooted in deficits and imbalances of these chemicals, and many psychiatric drugs are tasked with manipulating their levels. Therefore, if your gut bacteria are intimately involved with producing these vital chemicals, it stands to reason that when your gut bacteria are altered, you risk doing damage to this complex web of body and brain function. That’s a lot of responsibility for a group of microscopic organisms!

Different collections of bacteria affect brain chemistry differently. For instance, changes in proportions and function of Escherichia, Bacillus, Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus can result in changes in dopamine levels and may predispose one to Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (6). Other combinations of abnormal gut bacteria may result in abnormally high concentrations of acetylcholine, histamine, endotoxin, and cytokines, which can damage brain tissue.

In addition to regulating neurotransmitter levels, there are various other ways in which microbiota influence the gut-brain connection. They are involved in the production of other important compounds like brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which supports the survival of existing neurons and promotes new neuron growth and connections. They influence the integrity of the gut wall and the gut’s barrier function, which protect the brain and the rest of the body from substances that need to be confined to the gut. Bacteria can also have an effect on inflammation in the brain and body, particularly influencing oxidation, a harmful process that results in cellular damage.

A TWO-WAY STREET

As I mentioned earlier, the gut-brain connection works both ways. So if gut bacteria can influence the brain, it is also true that the brain can change gut bacteria.

All it takes is two hours’ worth of psychological stress to completely change the bacteria in your gut (7). In other words, a tense family Christmas dinner or unusually bad traffic can be enough to upset the balance of your microbiome. The theory is that the ANS and HPA-axis send signaling molecules to gut bacteria when you are stressed, changing bacterial behavior and composition. The results can be damaging. For example, one kind of bacterium changed by stress is Lactobacillus. Normally, it breaks down sugars into lactic acid, prevents harmful bacteria from lining the intestine, and pro- tects your body against fungal infections. But when you are stressed, Lactobacillus fails on all these fronts due to how stress disrupts its functioning, leaving you exposed to harm.

The brain can also affect the physical movements of the gut (for example, how the gut contracts), and it controls the secretion of acid, bicarbonate, and mucus, all of which provide the gut’s protective lining. In some instances, the brain affects how the gut handles fluid. When your brain is not functioning well — for example, when you have depression or anxiety — all these normal and protective effects on the gut are compromised. As a result, food is not properly absorbed, which in turn has a negative effect on the rest of the body since it’s not getting the nutrients it needs.

WHEN THINGS GO SOUTH

So to recap, your brain needs the proper balance of gut bacteria to make the chemicals it needs to stay stable and healthy. The gut needs your brain to be stable and healthy so that it can maintain the proper balance of gut bacteria. If that cyclical relationship is disrupted, it means trouble for both the gut and the brain. An unhealthy gut microbiome leads to an unhealthy brain, and vice versa.

A quick illustration of these issues is provided by a survey Mireia Valles-Colomer and her colleagues conducted in April 2019 of more than a thousand people, in which they correlated microbiome features with well-being and depression (8). They found that butyrate-producing bacteria were consistently associated with higher quality-of-life indicators. Many bacteria were also depleted in people with depression, even after correcting for the confounding effects of antidepressants. They also found that when the dopamine metabolite 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, which helps gut bacterial growth, is high, mental health is improved. GABA production is disturbed in people with depression too.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg. In each chapter of this book, we will go into specific gut-brain disturbances that map out the relationships between the microbiome and individual disorders. In the pages to come, we will see how depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dementia, obsessive compulsive disorder, insomnia, decreased libido, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder might all be associated with an altered microbiome. For each condition, I will walk you through where we stand with research today and give you an idea where there may be room for further study.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

In addition to exploring how disruptions in gut bacteria can cause these kinds of mental issues, we’re also going to keep our eyes peeled and our appetites sharp for foods that can help encourage a healthy gut and a healthy brain.

Food influences your brain directly and indirectly (9). When food is broken down by the microbiota into fermented and digested materials, its components directly influence the same kinds of neurotransmitters we’ve been discussing, such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, which travel to the brain and change the way you think and feel. When food is broken down, its constituent parts can also pass through the gut wall into the bloodstream, and certain metabolites can act on the brain that way as well.

As we’ve already touched on, food’s most profound effect on the brain is through its impact on your gut bacteria. Some foods promote the growth of helpful bacteria, while others inhibit this growth. Because of that effect, food is some of the most potent mental health medicine available, with dietary interventions sometimes achieving similar results to specifically engineered pharmaceuticals, at a fraction of the price and with few if any side effects.

On the other hand, food can also made you sad — certain food groups and eating patterns can have a negative effect on your gut microbiome and your mental health.

Throughout the book, we will examine foods that both help and hurt mental health. You will learn how to use healthy, whole foods to ensure that your brain is working at peak efficiency. In chapter 11, I will provide you with sample menus and recipes that will boost your mood, sharpen your thinking, and energize your whole life.

THE CHALLENGE IN PSYCHIATRY

The idea of using food as medicine for mental health is central to nutritional psychiatry, and in my opinion, it’s crucial to finding meaningful, lasting solutions to mental health problems.

As I said at the beginning of the chapter, we’ve come a long way since the seriously mentally ill were confined to asylums or hospitals without much understanding of their suffering. But mental health is still in a crisis. More than 40 million Americans are dealing with a mental health concern — more than the populations of New York and Florida combined (10). Mental disorders are among the most common and costly causes of disability (11). Depression and anxiety are on the rise. Suicide is a staple on lists of top causes of death, no matter what age-group. We’re in a mental health mess, no matter how many people are in denial about it.

It has been challenging to find treatments that help people man- age their moods, cognition, and stress levels. Historically, we turned to evidence-based medications and talk therapies that worked for specific conditions. For example, for someone who was depressed, we might have tried a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor like Prozac. For someone who was panicky, we might have used cognitive behavioral therapy. Those kinds of treatments are still in wide use and can be effective. But for some people, the positive effects last only a short period of time, and they do not completely eliminate symptoms. Sometimes patients develop side effects from the medications and stop taking them. Other times they are afraid of becoming “dependent” on a medication and ask to be taken off it. Some patients who come to see me do not meet the criteria for a disorder such as depression or anxiety. They struggle with symptoms but not enough to warrant a medication intervention.

My own view of where we went wrong is this: psychiatric diagnoses have no statistical validity, and the conditions have no biomarkers of specific diseases (12). “Diagnoses” are simply lists of symptoms. We assume that when a person presents with psycho- logical symptoms, the problem rests solely in the brain. Given what we have reviewed so far, it is clear that other organs such as the gut play a role in how we think and feel. We need to examine the whole person and their lifestyle in order to better treat them.

The problem is bigger than psychiatry, extending to medicine as a whole. Despite the huge number of health issues that relate to diet, it may sound far-fetched, but many patients don’t hear food advice from their doctors, let alone their psychiatrists. Medical schools and residency programs do not teach students how to talk to patients about dietary choices. Nutrition education for doctors is limited.

Thankfully, we are inching toward a moment in health care when medicine is no longer strictly about prescriptions and a single line of therapy. Thanks to the wealth of medical knowledge accessible to the general public, patients are more empowered and informed than ever. It feels as though all my colleagues are experiencing a similar movement in their specialties, with patients eager to explore a diverse range of ways to feel better. One of my success stories of nutritional treatment was a referral from an infectious disease colleague. Another time, an orthopedic colleague reached out to me to ask more about the data on turmeric as an anti- inflammatory, as his patient with severe knee pain wanted to delay surgery until he’d tried this nutritional intervention.

In psychiatry, we are finally beginning to talk about the power of food as medicine for mental health. The body of research on the microbiome and how food impacts mental health is growing. In 2015, Jerome Sarris and his colleagues established that “nutritional medicine” was becoming mainstream in psychiatry (13).

The goal of nutritional psychiatry is to arm mental health professionals with the information they need so that they can offer patients powerful and practical advice about what to eat. With this book, my goal is to offer you, the reader, the same kind of information. That doesn’t overshadow the importance of working with your doctor, since medication and the appropriate therapy remain a part of the journey to improved mental health. A better diet can help, but it’s only one aspect of treatment. You cannot eat your way out of feeling depressed or anxious (and in fact, as we’ll see, trying to do so can make things worse). Food is not going to relieve serious forms of depression or thoughts of suicide or homicide, and it is important to seek treatment in an emergency room or contact your doctor if you are experiencing thoughts about harming yourself or someone else.

As I found in my battle with cancer, it is also extremely important to look after your mental health with strategies of mindfulness, meditation, exercise, and proper sleep. The literature on these topics is vast, with methods both ancient and modern (and sometimes a combination of the two!). I won’t go into detail about those topics in this book, but I encourage you to explore them on your own.

That being said, in addition to taking guidance from your doc- tor and encouraging mental wellness in other ways, you should support your treatment by paying attention to how and what you eat. The relationship linking food, mood, and anxiety is garnering more and more attention. In the chapters that follow, I will guide you through the exciting science of food and its connection to a variety of common mental health challenges.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

To better guide you through the science behind how food affects mental health, I’m going to explore ten different mental conditions over the course of this book. Of course, no one reader will need every chapter — you see a lot as a clinical psychiatrist, but thank- fully, even I haven’t seen a patient who is suffering from every condition we will discuss. It’s important to me that readers be able to skip around to the chapters that apply to them most, so I’ve arranged each chapter to be as self-contained as possible. If you’re reading straight through, you’ll likely start to notice trends in the advice as we see how various foods and eating patterns affect different conditions in similar ways. Since all the conditions we will talk about are rooted in the gut-brain connection, there is naturally overlap in the foods that worsen and improve them, so be aware that you will see the same recommendations come up multiple times. In each chapter, I will present the studies that support eating or avoiding foods for the given condition.

As you read the book, I encourage you to do so with an open mind. Nutritional psychiatry is just one part of a complex puzzle, and the amount of evidence differs for different foods. Most of the evidence showing that microbiome changes affect the brain comes from animal studies. But several human studies have now also demonstrated the key connection between microbiota and mental health, and I’ll include as many human studies as possible in our discussions.

It’s also important to note that in many of the studies we cover in the book, researchers supplied the nutrients they studied through dietary supplements. Supplements can help fill in nutritional gaps, but I believe you should always try to get your nutrients from your daily diet first. If you do want to incorporate supplements into your routine, always consult your doctor to ensure you’re getting the dos- ages correct and there are no interactions with medications you are taking. For example, many people don’t realize that the innocent grapefruit and related food products like grapefruit juice interact with many medications due to a chemical compound that blocks certain liver enzymes.

Conventionally, good evidence in medicine means that there have been at least two double-blind clinical trials showing that a treatment has efficacy over a placebo control. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study means that the clinical trial participants may receive the real medication or an inactive substance that looks exactly like the medication (called a placebo). Neither the participant nor the researcher will know which medication (real or placebo) they are receiving. That’s the only way to make certain that the real drug is effective.

The problem with double-blind trials is that they give you data on a group of individuals, not the individuals themselves. The group’s characteristics may not reflect each unique brain. The only way to truly know what works for you is to experiment on your own. While you should never experiment with medication or even dietary supplements without consulting a doctor, as long as you are sticking to healthy, whole foods, I encourage you to try eating different things to see what diet makes you feel best. This book is intended to be a rigorous but realistic guide on how to choose foods based on your current mental health challenges. In each chapter, I will provide guidelines on each food’s or diet’s efficacy and safety and give you an idea of the current research and data that support my suggestions.

Of course, this information will likely change as time goes on, as medical knowledge shifts with the release of new studies and research. It doesn’t make things easier that nutritional epidemiology has a tendency toward problematic data interpretation. For example, as I write this book, a recent series published in the Annals of Internal Medicine is dominating headlines with the claim that there are no health benefits for reducing red meat consumption. I cannot realistically support the conclusions reached by these articles, and I will just reiterate that in making the carefully balanced guidelines presented in this book, I have steered clear of sensationalized nutrient research and outcomes.

Finally, I want to emphasize that psychiatry is a complicated and individualized field. I am by no means suggesting that every patient who suffers from the conditions we are about to explore will find total relief solely through diet. It’s important to work with a mental health professional to develop the right mix of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication when necessary. But no matter what, the food you eat will be an important part of the puzzle.

THE WAY TO A PERSON’S BRAIN

There’s a proverb that states that the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. We might have stumbled upon a great truth with slight modification: for both men and women, the food that enters our stomachs can warm our hearts and change our brains.

May this book help bring you greater clarity, calmness, energy, and happiness. Let the exploration begin!

References

- If you’d like to learn more about how mental health was viewed before 1800, I recommend reading Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (New York: Vintage, 1988) by Michel

- Miller I. The gut-brain axis: historical reflections. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease. 2018;29(2):1542921. doi:10.1080/16512235.2018.1542921.

- Miller I. The gut-brain axis: historical reflections. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease. 2018;29(2):1542921. doi:10.1080/16512235.2018.1542921.

- Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The gut-brain axis: inter- actions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2015;28(2):203–9.

- Simrén M, Barbara G, Flint HJ, et al. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut. 2012;62(1):159–76. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302167.

- Giau V, Wu S, Jamerlan A, An S, Kim S, Hulme Gut microbiota and their neuroinflammatory implications in Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):1765. doi:10.3390/nu10111765; Shishov VA, Kirovskaia TA, Kudrin VS, Oleskin AV. Amine neuromediators, their precursors, and oxidation products in the culture of Escherichia coli K-12 [in Russian]. Prikladnaia Biokhimiia i Mikrobiologiia. 2009;45(5):550–54.

- Galley JD, Nelson MC, Yu Z, et Exposure to a social stressor disrupts the community structure of the colonic mucosa-associated microbiota. BMC Microbiology. 2014;14(1):189. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-14-189.

- Valles-Colomer M, Falony G, Darzi Y, et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nature Microbiology. 2019;4(4):623–32. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x.

- Ercolini D, Fogliano Food design to feed the human gut microbiota. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2018;66(15):3754–58. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00456.

- New State Rankings Shines Light on Mental Health Crisis, Show Dif- ferences in Blue, Red States. Mental Health America website, October 18, 2016, https://www.mhanational.org/new-state-rankings-shines-light-mental-health-crisis-show-differences-blue-red-states. Accessed September 29, 2019.

- Mental Health and Mental Disorders. HealthyPeople.gov website, https:// www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/mental-health-and-mental-disorders. Accessed September 29, 2019.

- Liang S, Wu X, Jin Gut-brain psychology: rethinking psychology from the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2018;12. doi:10.3389/fnint.2018.00033.

- Sarris J, Logan AC, Akbaraly TN, et al. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):271–74. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(14)00051-0.