This 2015 trial compared the impact of a very low-calorie diet (VLCD) on metabolic markers in patients recently diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes versus in those who had suffered from the disease for years.

The study included 15 subjects with recently diagnosed diabetes (<4 years) and 15 subjects with long-term diabetes (>8 years). All 30 subjects were put on a diet of <700 calories per day for eight weeks (the diet consisted of 624 calories of Optifast shakes containing 268 calories from carbohydrate, 212 calories from protein, and 122 calories from fat, supplemented with a small amount of non-starchy vegetables and non-caloric drinks).

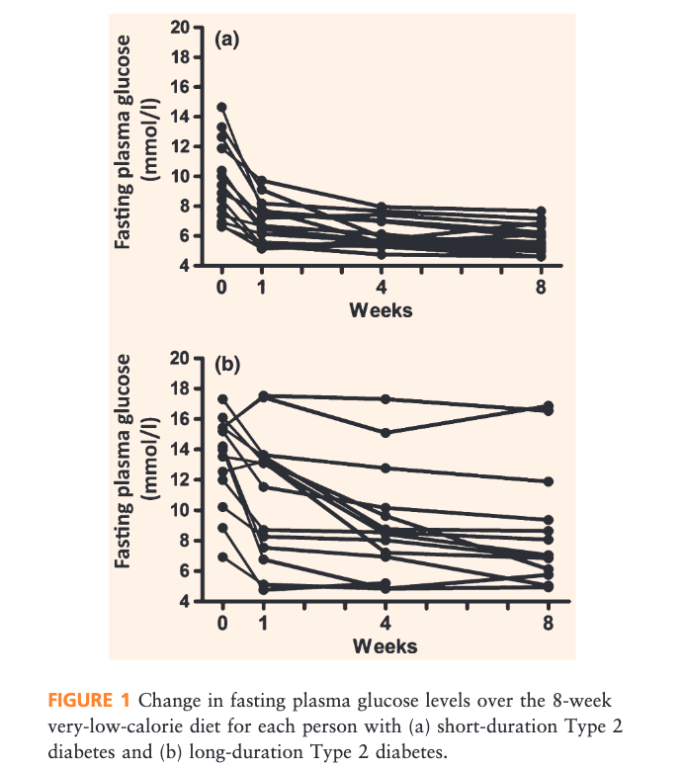

The subjects all showed significant weight loss, with a mean weight loss of 14.8% among recent diabetics and 14.4% among long-term diabetics. Both groups also showed significant decreases in fasting plasma glucose, but the response profile differed dramatically. Among recent diabetics, all subjects showed a rapid decrease in fasting plasma glucose within the first week (mean decrease: 9.6 to 5.8 mmol/L). Among long-term diabetics, some subjects failed to respond at all, some responded rapidly, and some showed a gradual decrease in fasting plasma glucose over eight weeks (mean decrease: 13.4 to 8.4 mmol/L). By the end of the trial, 87% of recent diabetics and 50% of long-term diabetics showed non-diabetic fasting glucose levels. All antidiabetic medications were discontinued prior to the study, so these results indicated diabetes resolution in 13 out of 15 recent diabetics and seven out of 14 long-term diabetics. Figure 1 summarizes these results.

fig 1

Across both groups, the impact of treatment decreased with age, duration of diabetes, and intensity of diabetes treatment prior to study initiation.

The decrease in blood glucose level was paired with significant decreases in blood pressure and total cholesterol, which did not differ significantly between groups. The mean reduction in blood pressure (19 to 27 mmHg systolic, 9 to 10 mmHg diastolic) had comparable effects to adding two anti-hypertensive medications, while the mean reduction in total cholesterol (~1 mmol/L) was similar to that seen in full-dose statin therapy.

Significantly, 29 of 30 subjects were able to comply with the VLCD protocol for the full eight weeks (the single dropout did not meet anticipated weight-loss targets, a marker for compliance). This suggests the VLCD is feasible over at least an eight-week period in diabetic populations. The authors note that previous research has shown enthusiastic compliance with VLCDs as their benefits—particularly a reduction in medication intensity coupled with general improvements in quality of life—become apparent.

This trial demonstrates that a VLCD can lead to rapid resolution of diabetes and improvements in blood pressure and lipid levels in as little as one week in recent diabetics and in as little as eight weeks in half of long-term diabetics. These results suggest such diets may be a potent and underutilized tool in diabetes treatment, particularly in light of other research suggesting the same. Given the main limitations of this trial—small sample size and relatively short duration—future research should look to replicate these results across larger populations and test the long-term impact and sustainability of the treatment.

Comments on Restoring normoglycaemia by use of a very low calorie diet in long- and short-duration type 2 diabetes

Imagine mixing the VLCD and CrossFit methodology and it's effect on T2D.

Would love to know the level of activity of those involved in the research. Should be interesting to know if the VLCD supports or not high levels of activity. Very interesting stuff, nonetheless. Thanks for sharing.

"Small sample size". Is it really a limitation here? I'd suggest not. The study shows that the intervention was effective in 29/30 participants. And the one for whom it was not effective did not comply with the study protocol. So that's 100% effective for people who follow instructions. How many more participants would be needed to make the findings definitive? 10? 20? 100? 1000? It's like asking how many apples did Newton need to see fall from his tree to prove universal gravitation. How many smokers need to die of lung cancer or heart disease to prove the link between smoking and premature mortality?

Based on fundamentals of inferential statistics and probability theory (e.g. the law of large numbers), I'd suggest that we can be quite confident that this study's results justify conclusions that have better than chance predictive value. Reducing calories is an incredibly effective treatment for type 2 diabetes.

In a practical sense, you're entirely right. I am convinced based on this study that in - at the very least - a very large share of the diabetic population, significant caloric reduction can lead to rapid improvements and even resolution. If there is any value in a larger sample, it would be to find whether there are a small number of exceptions in the population that don't respond, or respond with side effects. But this is also data that could be gathered in clinical practice, so long as patients are monitored properly. Thank you for the comment, it's a great point.

Restoring normoglycaemia by use of a very low calorie diet in long- and short-duration type 2 diabetes

4