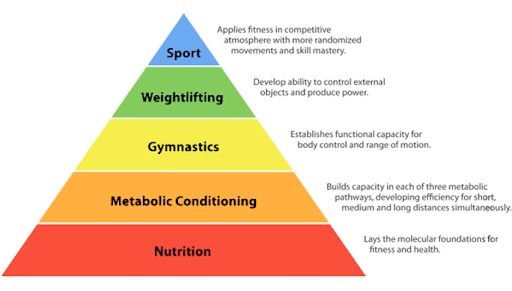

In 2002, Coach Glassman wrote the seminal article “What is Fitness” and outlined the Theoretical Hierarchy of the Development of an Athlete. This ranking, ordered not by CrossFit but by nature, illustrates that each layer depends on the supporting layers below. Nutrition — the inputs to the system — is placed squarely at the foundation.

In the same article, “World Class Fitness in 100 Words,” begins with the now infamous line: “Eat meats and vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, little starch, no sugar.”

Consider this: the first line of the prescription for achieving world-class fitness has nothing to do with exercise or training.

It tells us what to eat.

But before we dive into the details, we need to zoom way, way out to ponder a big-picture question:

Why do we need to eat? What is food for?

When posed this question, most people will respond with an enthusiastic “Fuel!” or “Energy!” While this answer is correct, it is also incomplete. It’s true that food provides hydrocarbons (fats and carbohydrates) that get turned into ATP (the energy currency of the body). But just as important, if not more so, food also provides building blocks — structural elements that do not get used for energy but get turned into our brain, muscles, bones, connective tissue, blood vessels, neurotransmitters, etc. Every bit of you is built out of something you ate.

In the CrossFit nutrition prescription, “eat meats” is offered as a placeholder for animal products in general — meat, eggs, fish, dairy, etc. The primary macronutrient in these foods is protein. When consumed and digested, dietary protein is broken down into amino acids. Think of amino acids like Lego blocks and proteins as the near-infinite number of creations we can construct out of them. There are 20 amino acids used to build proteins in the human body, nine of which are essential (meaning we have to get them from the diet) and another six that can become essential depending on factors such as training volume, illness, injury, etc. From these amino acids, the body produces at least 20,000 proteins that we know of. Some are small, such as the hormone insulin, constructed of just 51 amino acids linked together. Other proteins are enormous. Titin, found in the sarcomere of muscle, is the largest protein in the body and is composed of approximately 34,350 amino acids!

This six-part series will explore the underappreciated but necessary structural elements of the diet and all the weird and wonderful ways the body uses dietary protein to support good health.

Defining health as “work capacity across broad time and modal domains, across the years of your life,” what better place to start than with skeletal muscle?

Muscles

When we work out, we cause damage to muscle tissue as muscle fibers break down under stress. In the days that follow, our body uses the protein from our food to repair the damage, producing tissue stronger than before and better prepared to handle that demand again in the future. One amino acid in particular, leucine, triggers this process of muscle protein synthesis more than the others. We find high concentrations of leucine in whole foods like beef, chicken, pork, tuna, salmon, cod, and cheese.

While more thrusters and a bigger clean and jerk are cool, as we progress through life, our muscle mass and muscle function become the most significant predictors of how well we will age. Muscle has been dubbed the organ of longevity, a “health pension account” of sorts. When it comes to preventing chronic disease, muscle is the primary organ of glucose disposal, helping us maintain healthy blood sugar levels and avoid Type 2 diabetes. It sends signaling molecules to the brain that keep us sharp and mentally flexible. And, of course, muscle is the most critical inoculation against decrepitude, the loss of functional capacity that robs a person of their ability to live independently when they can no longer get up off the toilet, navigate stairs, and carry their groceries. It is well known that diet plays a significant factor, with one meta-analysis finding that older adults with sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) consume significantly less protein than their peers with no sarcopenia. However, the risk is not just loss of quality of life but of life itself. Low skeletal muscle mass has repeatedly been shown to be one of the strongest predictors of all-cause mortality, which is to say, who will die of anything.

In short, more muscle = less dead.

About the Author

Jocelyn Rylee (CF-L4) and her husband David founded CrossFit BRIO in 2008, starting in a modest 1500 sq ft space and focusing on personal training. Her dedication to excellence has also earned her a position on CrossFit LLC’s Level 1 Seminar Staff, a role that allows her to share her passion and expertise with aspiring coaches. Jocelyn holds specialties in Endurance, Gymnastics, Competition, and Weightlifting and is also a certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA. As a Level 2 Olympic Weightlifting Coach and a Level 3 referee, she has been deeply involved in the sport, even serving as a board member of the Saskatchewan Weightlifting Association for five years. Her achievements include being Saskatchewan’s top-ranked female Olympic Weightlifter from 2012 to 2015, during which she held provincial records in the Snatch, Clean & Jerk, and Total in her weight class. With an MS in Human Nutrition, Jocelyn loves sharing her knowledge on nutrition and performance through her blog and Instagram as “The Keto Athlete,” where she delves into the science of nutrition and its impact on athletic performance.

Jocelyn Rylee (CF-L4) and her husband David founded CrossFit BRIO in 2008, starting in a modest 1500 sq ft space and focusing on personal training. Her dedication to excellence has also earned her a position on CrossFit LLC’s Level 1 Seminar Staff, a role that allows her to share her passion and expertise with aspiring coaches. Jocelyn holds specialties in Endurance, Gymnastics, Competition, and Weightlifting and is also a certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA. As a Level 2 Olympic Weightlifting Coach and a Level 3 referee, she has been deeply involved in the sport, even serving as a board member of the Saskatchewan Weightlifting Association for five years. Her achievements include being Saskatchewan’s top-ranked female Olympic Weightlifter from 2012 to 2015, during which she held provincial records in the Snatch, Clean & Jerk, and Total in her weight class. With an MS in Human Nutrition, Jocelyn loves sharing her knowledge on nutrition and performance through her blog and Instagram as “The Keto Athlete,” where she delves into the science of nutrition and its impact on athletic performance.

Comments on The Primer on Protein: Part 1 - What Is Food For?

I replaced eating just vegetables and lots of fruit during the day and only meat a couple of days a week to mostly just eating meat and eggs, im 49 and look better feel like i always have energy and performing better at crossfit

Great to relearn some points that have been forgotten and learn some new ones, excited for the rest of the articles.

The Primer on Protein: Part 1 - What Is Food For?

2