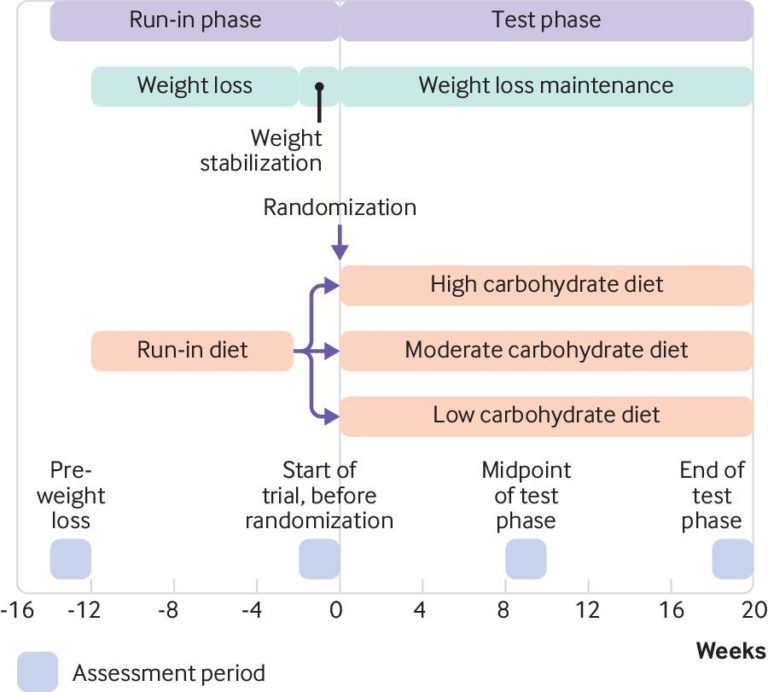

This trial at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School tested whether different diets affect energy expenditure after weight loss, with the implication that a diet that increases the number of calories we burn might make it easier to keep weight off. A total of 164 overweight or obese subjects first lost 12 percent of their body weight by cutting their calorie intake by 40 percent. Once this weight loss was achieved, they were randomized to a low-, medium- or high-carb diet, continually adjusting calorie intake so weight remained stable for 20 weeks.

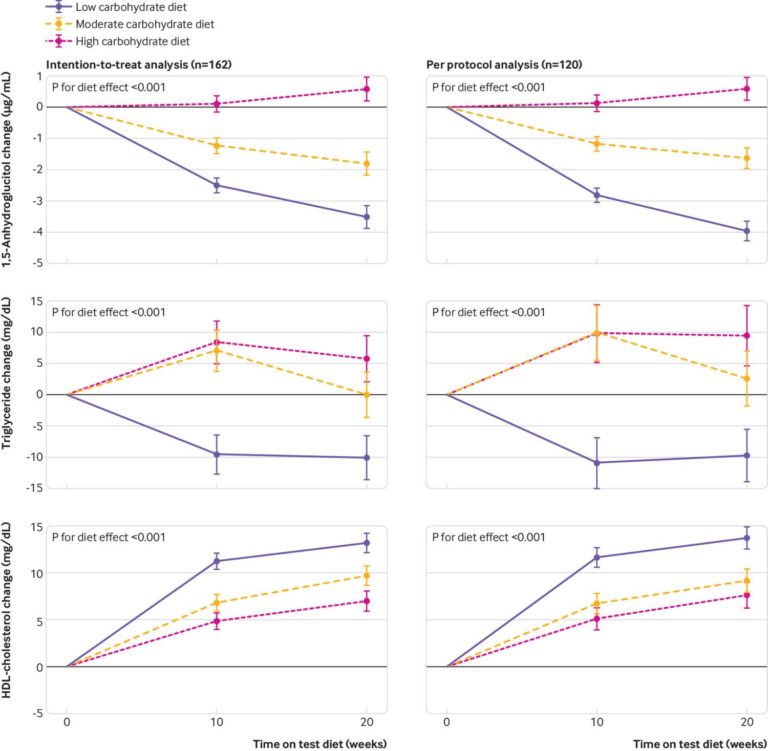

At the end of 20 weeks, energy expenditure was 209 kcal/d higher on the low-carb diet than on the high-carb diet (and 91 kcal/d higher on the moderate-carb diet). Among those with high insulin secretion at baseline, the difference between low- and high-carb diets was 308 kcal/d. The low-carb diet was also associated with lower triglycerides and greater increases in HDL than moderate- or high-carb diets.

Figure 2: From the BMJ: “Biomeasures of compliance in intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses. … Data are shown as mean change from start of test phase, with whiskers representing 1 standard error above and below the mean. P tests uniformity across diet groups for average of changes at midpoint and end of test phase. Left, intention-to-treat analysis; right, per-protocol analysis.

“Consistent with the carbohydrate-insulin model, lowering dietary carbohydrate increased energy expenditure during weight loss maintenance. This metabolic effect may improve the success of obesity treatment, especially among those with high insulin secretion,” the authors concluded.

These results suggest that maintaining weight loss, especially for individuals with hyperinsulinemia, might be easier on a low-carb than a high-carb diet. More importantly, it shows that the composition of the diet meaningfully affects how the body reacts to a weight-reduced state, and thus certain diets that target the metabolic defects associated with weight gain might support effective weight loss.

From the study:

In this controlled feeding trial over 20 weeks, we found that total energy expenditure was significantly greater in participants assigned to a low carbohydrate diet compared with (a) high carbohydrate diet of similar protein content. In addition, pre-weight loss insulin secretion might modify individual response to this diet effect. Taken together with preliminary reports on activation of brain areas involved in food cravings and circulating metabolic fuel concentration, results of the current Framingham State Food Study (FS)2 substantiate several key predictions of the carbohydrate-insulin model. Regardless of the specific mechanisms involved, the study shows that dietary quality can affect energy expenditure independently of body weight, a phenomenon that could be key to obesity treatment, as recently reviewed.

Comments on BMJ: Randomized Trial on the Effects of a Low-Carb Diet

Fat contains more kcals than carbs. If we limit carb intake,

the body is forced to use more fat for energy expenditure, thus the increase in

energy expenditure in the low carb group is reasonable to assume that it would

happen. And I’m not saying that it’s a bad thing, especially in a population

that is so insulin resistant.

My question would be, if this same diet approach were tried

on an athletic population that are at a health weight, body fat percentage, and

triglyceride level, would we see the same results and how would that effect their

individual performance, not just energy expenditures?

As always, great stuff. Thank you!

If you want to loose weight (body fat to be exact) and keep it off getting off the carbs is a step in the right direction.

I really appreciate CrossFit posting/referencing from the scientific scholarly articles with a good summary and the discussions can be focused around this.

It's a huge opportunity. There are so many filters between academic research and non-academic audiences that far too often the actual story the data show is not the story that gets reported. As the 10/10 Crossfit.com posts show, I think this study has been reported on pretty well by the media...but most of these papers can be made pretty intuitive as long as they're explained well enough.

It's a really important step to be focusing our discussions on the data itself and the ways it can be interpreted, rather than on second- (or even third-)hand interpretations of that data. Often clears up much of the confusion around these studies in the process.

These results were largely reflected in the first 10 weeks, with little change over 11-20 weeks, it seems. “ Total energy expenditure did not change significantly within any diet group between 10 and 20 weeks” Is this a viable long-term option?

1. I'd relate that to how people respond to training and workouts. Early in the novice phase people adapt quickly and all over the place, then as they get into a more intermediate phase results still happen but are less and farther between, and the trend carries on into advanced and elite level. 2. Since there is no data after the 20 weeks, it can't be said which one would be viable long-term, but what do you think?

Good question Lisa. I believe attention should be drawn to the fact that all three diets were successful in maintaining weight loss over the course of the 20 weeks. This tells us that beyond the 20 week mark, any three of these would be candidates to that end goal.

The key take away here is the evidence pointing toward physiological change beyond weight control. The evidence suggests that a low-carb diet may have a greater positive effect on triglyceride and HDL levels beyond the 20 week mark. Further, this may be enhanced in insulin resistant individuals.

It would be interesting to see the necessary caloric modifications during the "test phase" to keep the subjects in "weight loss maintenance". Change in calorie consumption, in any of the three diets, over the course of the 20 weeks would give more direction to long term studies.

Hi Lisa,

The safest interpretation is that this study can’t tell us anything about periods beyond 20 weeks. However, the fact that energy expenditure did not keep increasing between 10 and 20 weeks does not mean the effect of the low-carb diet on metabolism was decreasing - in fact, quite the opposite, it means it increased and remained stable. It would be reasonable to interpret this data as saying it takes less than 10 weeks for a low-carb diet to increase energy expenditure, and this increase is sustained over time.

There are two other caveats mean we should only apply this study to the long-term with caution:

1. A major reason most diets don’t work in the long term is compliance. That wasn’t an issue here - everybody was given all their food, so compliance was either perfect or very close to it. It doesn’t tell us anything about how a 20% vs. 40% vs. 60% carbohydrate diet may fare in long-term practice. The low-carb diet might be easier or more challenging to comply with.

2. In the “trial phase”, weights were fixed. If somebody started losing weight, they were fed more calories, and vice versa, so their weight remained stable. This was done to counter the fact that, as we lose weight, our energy expenditure drops. (There’s simply less body to expend that energy) If weight was allowed to “float” - say, everybody was fed a 2000-calorie diet of 20%, 40% or 60% carb (a more realistic real-world prescription), the short- and long-term impact might be different.

These caveats might seem funny, but they really point to the core purpose of this study. Ludwig et al were looking to understand how a change in diet composition specifically affects energy expenditure after weight loss, so they designed a study to remove the impact of some factors with real-world significance but that confound energy expenditure - namely appetite (the # of calories people choose to eat on different diets) and weight gain/loss. The result was a very clear signal, showing an inverse association between carb consumption and energy expenditure. It’s a reasonable baseline assumption to argue these effects would be similar in less-controlled, real-world circumstances. (I think other literature would support this assumption as well…in particular, I know multiple studies have shown low-carb diets reduce voluntary calorie intake, which could further enhance its impact on net calorie balance.) But it’s not an inference we can explicitly make based on this study.

BMJ: Randomized Trial on the Effects of a Low-Carb Diet

8