When I started coaching gymnastics in the mid-80s, coaches didn’t often take courses on coaching, communicating, listening, influencing, or any other aspect of leadership. We just copied what we saw, or what you might call “pattern matching.” If a coach I respected offered a correction to a skill, I followed their instruction. If the coach had Olympians or National Champions and delivered corrections in an aggressive, angry fashion, well, that’s clearly what you were supposed to do because, well, medals.

The predominant type of leadership exercised by the best coaches was dictatorial or authoritarian — the coach tells athletes what to do and they are supposed to do it without question. Quick compliance was the goal, questioning was bad, and complaining about how the instruction made you “feel” was not even a thing.

That’s also the way humans have understood leadership for most of the 50,000 years of organized human society. It’s the way “management gurus” instructed business people in the early 20th century. It’s the way U.S. military organizations have operated through most of history: “If I tell you to jump, you should just jump and ask how high on the way up” used to be a common interpretation. And it is the most influential approach to elite-level coaching in athletics for the last century. The coach is the boss and possesses unquestioned authority.

This transactional approach can work if you’re trying to get someone to do something quick once or twice in dangerous situations. It’s a viable option and a tool you should have in your leadership kit.

It wasn’t until a full decade into my gymnastics coaching career that I started to question the way we understood and delivered corrections. I became curious about the effect of dictating and the way that use of power impacted both gymnasts and coaches. A whole bunch of reading, research, and a doctorate later I had learned that the word “coach” is not about making someone listen to your orders. It actually has Hungarian roots and literally means “to journey with.” Pretty different from “dictate to or at.”

One of the best things about CrossFit is our community. Our people come together to experience shared suffering (a powerful tool for human bonding) in the pursuit of individual growth and improvement. We’re not normal humans and most of us are eager to be coached so we can work so hard and fast that we truly explore the margins of our discomfort. CrossFit members tend to be rule followers who value structure and direction, and might seem pretty receptive to the dictating model of coaching. The downside of that is that it can be very easy for a coach to feel and exercise the power of leading a CrossFit class in a way that undermines the environment we’re trying to create: the internal, or intrinsic, motivation that keeps members coming back and dedicated to the pursuit of fitness for the long term.

A coach at Burg CrossFit demonstrates a movement.

Teaching a class is a really interesting leadership laboratory because students are compelled to listen to you and there is a lot of built-in, pre-established respect for the person standing in front of a room or a gym. However, if you don’t approach the class by thinking through how you’re leading them and evaluating how the athlete-coach relationship is playing out at the individual and group level, you’re missing out on a huge opportunity.

Most of us coach because we want to make a difference, not because we want the power or authority that comes with the role. If you want to be a positive influence, start by investing in your leadership skills just like you would work on a snatch or a muscle-up — understand the movement, build the foundational strength, drill progressions, execute, seek corrections, and keep working.

Start with an understanding of your personality style and what feels natural and authentic to you — I promise that your natural preference will fit with some of your members and situations. But it turns out humans aren’t complicated, we’re complex. We all see the world differently based on lived experience, identity, family history, cultural norms, and what state we’re in during a given day. Complexity means you can’t begin to predict with certainty how a human will react to an input or instruction because we have so many moving parts and variables. That complexity means we need to work to understand the people we’re attempting to lead at some level in order to establish a trusting relationship and appreciate how each individual needs to hear the message you’re trying to send. If you have mastered the beautiful framework of observing and correcting movement in the Level 2 Course, you have only one piece of the puzzle.

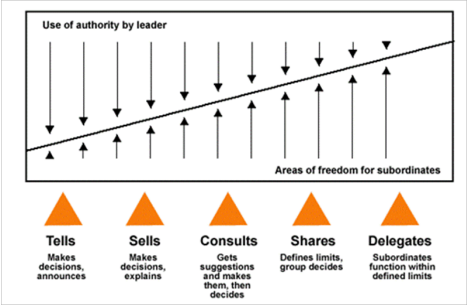

This is super wonky, but there’s something called the Tannenbaum-Schmidt Leadership Continuum that nicely captures the idea that leadership style falls on a continuum.

The far left starts with the leader having all of the authority, telling people what to do with no interaction. This works well if you need someone to escape a burning building, or you need a member to not pick up the barbell with an uneven load that looks like a disaster waiting to happen.

As you move to the right, the leader exercises less power, gradually giving more freedom and agency to the follower. On the far right the leader sets the broad direction or tone and gives the followers near complete freedom to accomplish a task or operate. This might be the approach you take with a longtime member who is a good mover, has their ego in check, and has shown the ability to scale appropriately.

In between are all of the possibilities dictated by the programming of the day, the people in your class, the things going on in their lives, and your own well-being as a coach. A coach who is an effective leader takes all of those factors into account and attempts to meet each member where they are with the right information and the right approach to balance the member’s need for external motivation vs. internal inspiration. But that requires a commitment to your leadership practice that includes the following:

1.) Self-awareness: Are you getting all of your basic needs met so you’re in the most patient, thoughtful place possible? Are you entering the class environment with a clear focus on serving others, rather than meeting your own needs or being an entertainer? Take advantage of a personality profile instrument, collect feedback from your peers and members, and try to understand where you fit on that continuum. Then you can work on stretching your natural self to use the best leadership approach in any situation.

2.) Other awareness: Have you spent the time necessary to start building a relationship of trust with your members so they believe you care about them as individuals? This is impossible when we churn through classes like a globo gym. Great CrossFit coaches work to understand their members in order to tailor both their content and delivery to each member and their needs.

3.) Lifelong learning: Read interesting things that help you better observe and understand human behavior. A good place to start is modern thinking about motivation (external) vs. inspiration (internal). People can be motivated for the short term, but long-term inspiration requires things like connection, agency (you get to choose), purpose (why am I doing this or why are you telling me this?), and mastery (am I actually getting better?). And it’s absolutely helpful to get coached on your coaching. Ask someone whose opinion you value how they rate your leadership as well as your cues and delivery.

Dave Castro briefs athletes at the CrossFit Games.

Final thought – A great example of effective leadership in our community is Dave Castro. From the outside, people have a lot of opinions of the Dave they encounter on social media or TV. You might guess that he lives on the left side of that continuum (and I thought the same). After judging a decade worth of CrossFit Games, I learned that Dave has a really nuanced and effective understanding of leadership. The people I worked under at the Games (mostly Seminar Staff) are the most talented, professional, and inspirational group of humans I’ve encountered, and they would all run through walls for Dave, even when it seemed like he was a crazy man ordering unreasonable changes. He effectively built personal, authentic relationships with each of them and understood how they worked and what they needed. He developed a sustainable, intrinsically motivating culture with his people. And when I would have rare individual encounters with Dave, he inevitably came across as kind, gentle, and open. I suspect this is a result of life as a SEAL — the more elite the unit in the U.S. military, the flatter the hierarchy, the more independent, and the greater levels of intrinsic motivation and inspirational leadership. Dave models all of those things and is adept at applying the right tool for the right person in the right circumstance. That should be all of our goals as coaches who lead.

About the Author

Dr. Mike Lorenzen, Ed.D., is the associate athletic director for leadership and professional development at UC Davis. He was a terribly untalented gymnast but a pretty successful gymnastics coach for 30 years. He matched that with a very undistinguished career as a competitive CrossFit masters athlete for over a decade, but a decent judging career over the course of 10 CrossFit Games. He has entertained CrossFit’s Seminar Staff with his frighteningly bad ankle and hip mobility at two CF-L2 Seminars (which he still passed and proudly uses, coaching CrossFit anywhere people might listen).