CrossFit’s core methodology, what we call “the kernel,” has been explained in great detail in original articles such as “Foundations” and “What Is Fitness?” as well as the What Is CrossFit? section on crossfit.com. These writings should be reviewed periodically to keep us grounded in the core methodology. Unfortunately, even with these great resources, it is very easy to be lured away from the kernel by the constant barrage of new diets, new methods, and even the criticisms of CrossFit we are all exposed to on social-media channels. This noise makes us start to wonder if Olympic lifts are dangerous, if we should be kipping our pull-ups, if supplements are the most important part of nutrition, or if mixing training modalities blunts the adaptation we’re looking for.

It is important to take a step back at times and reflect on what is essential in CrossFit — what must be preserved at all costs. In a nutshell, to preserve the CrossFit methodology and avoid sinking to the level of so many other fitness programs, we must do the right things and do them well. To do CrossFit right means we incorporate the most effective movements and we train in all the necessary time domains. To do CrossFit well means we demonstrate technical prowess before we add intensity.

Do It Right

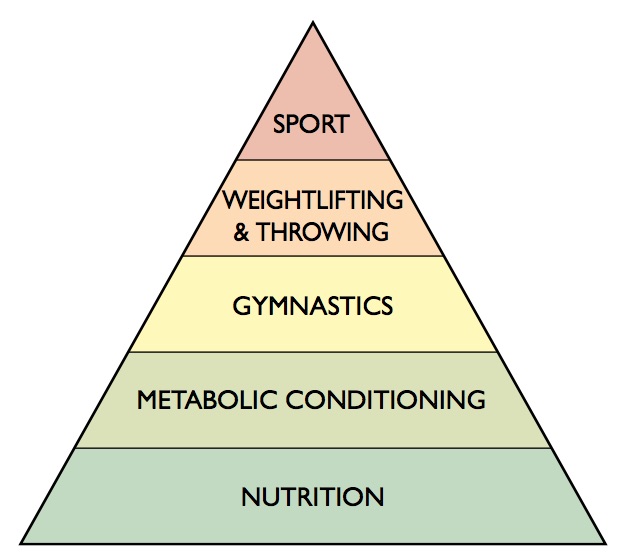

Theoretical Hierarchy of Development

CrossFit is a strength-and-conditioning program designed to optimize work capacity across as many diverse physical challenges as possible. This is how we define fitness. And we relentlessly pursue improved fitness, which is demonstrated as increased work capacity. Everything we do in CrossFit should be examined through this fitness filter. If something improves overall fitness or work capacity, it becomes part of the program. If it doesn’t, it gets dropped.

For example, nutrition is a foundational component of the CrossFit program precisely because of its tremendous impact on our ability to maximize our work capacity. Thousands of athletes have demonstrated that eating meat and vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, little starch, and no sugar while keeping intake to levels that support exercise but not body fat is a dietary formula for elite levels of fitness. These two charges describe the nutrition part of the kernel. While discussions of various diets, supplements, pre- and post-workout nutrition, and meal timing are fun, focusing on these minor details without adhering to the basics represents moving away from CrossFit’s core message.

When it comes to actual workouts and movements, “World-Class Fitness in 100 Words” clearly spells out the kernel: “Practice and train major lifts: Deadlift, clean, squat, presses, C&J, and snatch. Similarly, master the basics of gymnastics: pull-ups, dips, rope climb, push-ups, sit-ups, presses to handstand, pirouettes, flips, splits, and holds. Bike, run, swim, row, etc, hard and fast. Five or six days per week mix these elements in as many combinations and patterns as creativity will allow. Routine is the enemy. Keep workouts short and intense.”

CrossFit is hard. We incorporate taxing, technically demanding movements into our workouts because these are the movements that provide the greatest fitness benefit. We don’t dumb down CrossFit to make it easier for people to do. (Let our imitators and competitors race to the bottom by following that route.) Omitting challenging movements would be cheating our athletes out of the greatest rewards. To not do Olympic lifts or squats, deadlifts or presses, or gymnastics movements because they take time to learn and master is completely missing the point. CrossFit incorporates these movements because they are challenging to master. Practicing and performing these types of movements confers a much higher level of fitness than isolation movements or movements on machines. To leave any of these proven movements out of a program is straying from the kernel.

Similarly, CrossFit requires that we run, bike, swim, row, etc. hard and fast for long, medium, and short distances. If we decide we only like long and slow or short and fast, we’ll end up with a diminished work capacity and something that’s NOT CrossFit.

So, to adhere to CrossFit’s core methodology, we must follow its basic nutritional guidelines, and we must practice and incorporate the whole variety of effective movement patterns in as many different combinations as we can imagine, even — or especially — those patterns and combinations we dislike or fear.

Do It Well

Racing the clock, pushing for extra reps, and struggling to beat our previous best have become hallmarks of the CrossFit workout. And this intensity in CrossFit workouts is a crucial component for optimizing work capacity. However, to put intensity above technique is a dangerous violation of CrossFit’s core message.

CrossFit preaches mechanics and consistency before intensity. We must develop a certain level of mastery in our movements before we add intensity and attempt to perform these movements faster or with greater load. And there is no timeline for how long we must practice developing our technique. Only after we can move well and consistently well (no matter how long this takes) should we then add intensity to a movement pattern.

Take two athletes performing Fran. Athlete A scales to a lighter weight so she can move through full range of motion. During the workout, when she feels her technique degrade and she can’t fix it on the fly, she puts the bar down or stops her pull-ups, resets, and then attacks the reps again with improved technique. At the end of the workout, she is spent, but she did not beat her personal best.

Athlete B performs the workout as prescribed. As he fatigues, his elbows drop in the thrusters and his upper back rounds, knees cave in, and he gets pulled forward onto the balls of his feet. His range of motion is short at the top and bottom of the thruster. He fights through these sketchy reps and attacks his pull-ups. He doesn’t quite fully extend his arms at the bottom of each rep and at the top he tilts his head back and cranes his neck to push his chin almost over the pull-up bar. He finishes the workout gassed and he knocks 12 seconds off his personal best.

Athlete A is performing CrossFit as intended. By adhering to the principle of mechanics and consistency first, then intensity, she is following CrossFit’s core methodology. And because she is performing the workout at her threshold, even though she did not improve her Fran time, she is doing exactly what she should be doing to improve her fitness and health over the long term.

Athlete B has strayed from the CrossFit methodology by prioritizing intensity over mechanics and consistency. This is a common mistake and is a gross deviation from the kernel. Athlete B is not only blunting his work capacity by not performing the movements with proper technique, he is putting himself at greater risk of injury and an even more devastating decrease in his fitness and health. Let’s break this down even more.

1. Athlete B has not achieved a true PR because he achieved the 12-second win by reducing range of motion and therefore actually just doing less work.

2. Abandoning technique/mechanics may result in a faster time on the whiteboard, but it is not a foundation for continued and incremental improvements in work capacity over time. What does he do next to go faster? Shorten his range of motion even more? It’s a dead-end strategy.

3. It is subjective/speculative whether Athlete B is actually exposed to greater injury risk (although it makes intuitive sense, it often doesn’t play out that way and one common argument for continuing to move badly is “But I didn’t get hurt!”). A deeper point is that what you practice is what you become, and that affects every aspect of your life. Done right, CrossFit is restorative of correct movement patterns and posture and is rehabilitative. Done incorrectly, you remain trapped within the limitations/restrictions that you start with. Violate mechanics and you are blunting the restorative powers of functional movements.

The CrossFit methodology achieves such amazing results because it insists not only on doing the right things to maximize work capacity, but also doing them well. To truly observe the CrossFit kernel, we have to follow both of these principles.

About the Author

Stephane Rochet is a Senior Content Writer for CrossFit’s Education Department. He has worked as a Flowmaster on the CrossFit Seminar Staff and has more than 15 years of experience as a collegiate/tactical strength and conditioning coach. He is a Certified CrossFit Trainer (CF-L3) and enjoys training athletes in his garage gym. You can learn more about Stephane here.

Comments on Do It Right. Do It Well.

Simple and effective

Great recap about what CrossFit is all about and to get reminded again and again not to stray from the overall strcucture .Thus ensuring consistant progress .Slow down and do it right ..do it well

For me these are the biggest banner's of CrossFit:

For everyone's goals and for any age , fitness condition or any imaginable condition.

So we got to do it the best way possible.

Scaling it's just one of our toll's

Fallo bene,fallo bene 👊

I’m a little late reading this in that I’ve only just passed my L1 and recently started coaching. This is a great article and goes against the publics perception of CrossFit and what our aims are. This message should be pushed out there more often, I’ll certainly pass this on.

This was such a great read!!! Do the right things and do them well!! It inspired me to take my time in WODS and scale appropriately.

Great read! A good reminder for every coach.

Not to mention, they appear to be mostly 'no-reps' so he didn't actually shave time because he didn't actually finish

This is written so well, short and simple but purposeful. Comparing the athletes approaches is a great way to explain the impact of their performance against the methodology of CrossFit. This should be included in all training courses, participants should have to read this as a reminder of what CrossFit is really about. Thank you Stephanie and team!

Love the emphasis on the value of virtuosity. Keep up the helpful information!

Well said, thank you for this amazing article, Stephane!

Thank you for this article!

CrossFit should somehow figure out how to add this article into the L1 handbook or just make each L1/L2 participant read it during the course.

"A deeper point is that what you practice is what you become, and that affects every aspect of your life." - Preach and Amen. Great Article that should be included in every intro session, and repeated on the regular. 10/10 would read again.

Awesome articel; we need a shirt with that text on it

I love this! Is there a way to get these articles in PDF format?

I love this. Thank You !!

Love all of this, but especially highlighting "World-Class Fitness in 100 Words"!! So good, Stephane! Thank you for sharing.

thank you for share 💪🏻💙 it is very interesting and important to know this

Athlete A vs. Athlete B. Brilliant! More people need to read this…and follow it!

Working on my CSCS and needed this article today!!!

Well said, and well written. Great piece.

Amazing article!! Especially love the line that says “Let our imitators and competitors race to the bottom by following that route”.

Sometimes you just need a good reminder to shoot the home truths straight from the hip. This one nails it perfectly!

Nice work Stephane and the training department. Keep this stuff coming! :-)

Do It Right. Do It Well.