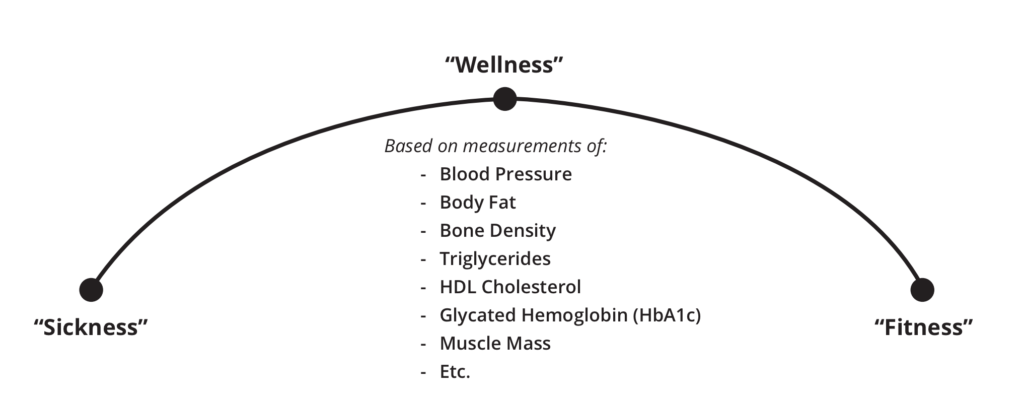

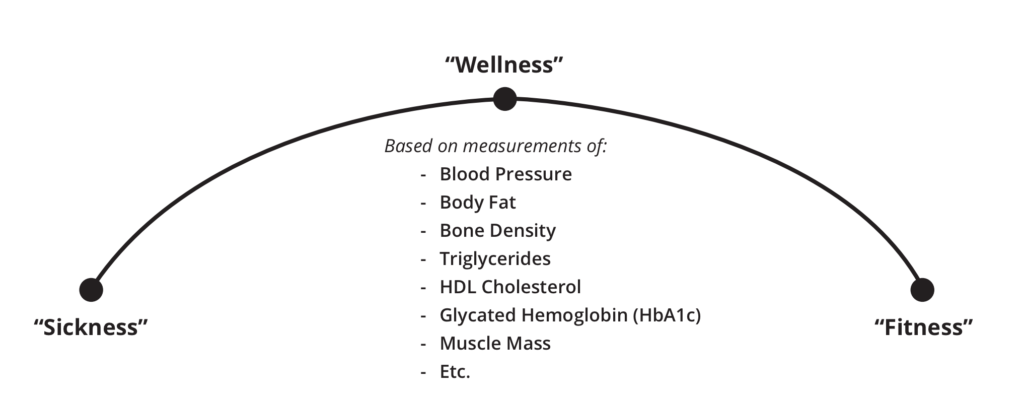

The Sickness-Wellness-Fitness Continuum: Our assumption is that everything we can measure about health will conform to this continuum. Therefore, sickness, wellness, and fitness are measures of a single quality: health.

For an athlete with prediabetes, simple food-quality improvements might be enough to move from sick to well on the Sickness-Wellness-Fitness Continuum pictured above. Your state of health lies somewhere on this continuum. Having one or more chronic diseases (including prediabetes) would signify being sick, being absent of disease with normal health-marker values would signify being well, and having optimal health markers signifies being fit.

Therefore, if prediabetes has progressed far enough, quantification will likely be recommended following the same guidelines outlined above for T2D. A reduction in carbohydrates and an increase in fat, while keeping calories consistent, might be necessary.

Coach’s tip: For athletes with T2D or prediabetes, a diet consisting of whole, unprocessed food in the optimal macronutrient ratios is ideal for reducing insulin resistance. Make sure the athlete is communicating any dietary changes with their physician just in case prescription medications need to be reduced. This can help prevent any risk of hypoglycemia.

Those with Type 1 diabetes can also benefit from dietary improvements. The standard treatment for T1D is insulin. A diet high in processed carbohydrates results in high levels of glucose in the blood. More insulin will be required to drive the glucose into muscle, liver, and fat cells if this becomes a chronic pattern. Eventually, these cells can become insulin resistant, and hyperinsulinemia can result. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia will increase the risk of other severe conditions, such as diabetic ketoacidosis and cardiovascular disease. Like T2D, a diet of whole, unprocessed foods can be extremely beneficial for those with Type 1 diabetes. These foods will lead to higher levels of insulin sensitivity, making exogenous insulin more effective and requiring less insulin to maintain blood-glucose control. Even with tight glucose control through diet, those with T1D will still have to be aware of any shifts in blood sugar before, during, and after exercise. It can still be helpful to have juices, glucose tablets, or honey available for quick increases in blood sugar, just in case hypoglycemia occurs. Quantification can also be a useful tool for an athlete with T1D. Knowing how much to eat and the proper macronutrient ratios necessary to maintain stable blood sugar is critical. Total intake and macronutrient ratios might have to be adjusted based on types of workouts, training volume, sleep, and stress, but they can provide a solid baseline, making it easier to adjust.

Coach’s tip: Reducing processed foods and eating mainly whole, unprocessed foods can increase insulin sensitivity. This would result in less insulin necessary for blood-glucose control. Make sure any athlete with T1D communicates these dietary changes with their physician to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia.

Daniele Hargenrader, who has Type 1 diabetes, monitors her glucose through a wireless device that allows her to train with intensity while also training smart.

Along with nutrition, exercise can be extremely beneficial to athletes with T1D, T2D, or prediabetes. In those with T2D and prediabetes, exercise can improve overall health by reducing body fat — especially visceral fat — reducing HbA1c, and increasing insulin sensitivity. Research has shown that exercise-induced HbA1c improvements are independent of weight loss. So both reductions in visceral fat and HbA1c can work somewhat independently to improve the metabolic profile of the T2D athlete. Reductions in fat surrounding the organs, most notably the liver, can reduce insulin resistance, while lower HbA1c values improve glycemic control. Both can result in better blood-glucose control, leading to a reduction in insulin-lowering medications. Research also shows that increases in exercise intensity can provide better HbA1c results. This supports CrossFit’s goal of managing an athlete’s relative intensity through proper scaling and threshold training.

Coach’s tip: Intensity is the pathway to results, but make sure to take the time to progress to the athlete’s relative intensity properly. Too much intensity too quickly can increase the risk of hyperglycemia and injury.

One consideration, as a coach, is to be aware of any medications your athlete is using to reduce blood glucose. Make sure your athlete is discussing their exercise plan with their physician. In combination with blood-glucose-lowering medications, the blood-glucose-lowering effect of exercise can lead to the risk of severe hypoglycemia. Be on the lookout for physiological signs of hypoglycemia in your athletes, such as shakiness, confusion, dizziness, changes in vision, tingling in the hands, irritability, clumsiness, and excessive sweating. In preparation, have juice, glucose tablets, or honey around for a quick increase in blood glucose. Another consideration specific to those with T2D is the risk of hyperglycemia and progression to diabetic ketoacidosis. This condition results from the liver producing glucose faster than it can be cleared from the bloodstream and is likely the result of high-intensity anaerobic training. This can be avoided by slowly progressing an athlete’s relative intensity through proper scaling and threshold training. Symptoms of acute hyperglycemia include extreme thirst, nausea and stomach issues, trouble seeing, poor concentration, confusion, disorientation, and high heart rate.

Coach’s tip: Ask about medications and make sure your athlete is communicating with their physician. As training progresses, medications may need to be reduced to avoid hypoglycemia. Increase intensity slowly to reduce the risk of hyperglycemia.

An athlete trains on the Assault Bike.

For athletes with Type 1 diabetes, exercise can help reduce the risk of long-term complications. An example is the reduced risk of cardiovascular disease through improved blood lipids and improved endothelial function. Typically, these improvements are the result of aerobic-style training. Anaerobic training can help improve insulin sensitivity, allowing for less insulin to be used for better blood-glucose control. There are some risks for both aerobic and anaerobic-style training. Prolonged aerobic training can reduce blood sugar to the point of hypoglycemia, and very intense anaerobic training can increase blood glucose to hyperglycemic levels. There are some strategies athletes can implement to reduce the risk of these events. For one, performing aerobic exercise while fasted has been shown to minimize reductions in blood glucose. Another strategy for athletes with T1D is to perform resistance training or a few short (approximately10-second) sprints before aerobic training to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia. It is also important to have juice, glucose tablets, or honey around to increase blood glucose quickly, if necessary. The signs of hypoglycemia in an athlete with T1D are the same as those mentioned above for athletes with prediabetes and T2D.

Coach’s tip: Make sure to keep blood-glucose-raising foods around for both T1D and T2D athletes to counter hypoglycemic events.

A strategy to reduce risk of hyperglycemia is to cool down slowly and aerobically. This could be something as simple as a 5-10-minute row, bike, or light jog to bring blood glucose down after an intense CrossFit workout. Symptoms of acute hyperglycemia for those with T1D are the same as those listed above with T2D athletes. Exercise timing should also be a consideration. Very intense training in the late afternoon and evening hours can result in nocturnal hypoglycemia, especially if the athlete used any post-workout insulin adjustments to bring blood glucose down. The aerobic cool-down can be a useful way to counteract and avoid this risk. As a coach, recommending this cool-down before insulin adjustments can reduce the amount of insulin used and reduce the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Coach’s tip: Use warm-ups and cool-downs to reduce the risk of severe blood-sugar fluctuations. If an athlete has a high blood-sugar reading and ketones present in the blood, the athlete should not exercise. Exercise under these conditions increases the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis.

As a CrossFit coach, it is important to understand the differences between Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes, and prediabetes. All three conditions involve compromised blood-glucose control and can benefit from lifestyle changes such as nutrition and exercise. That said, it is important to know the differences in the physiological responses to diet and exercise. Coaches should have a solid grasp of the different considerations and strategies used to decrease the risk of complications due to these lifestyle changes. A more knowledgeable coach is a more effective coach.

Download the printable Trainer Reference Guide below. This is a great resource that can be stored at the front desk of your affiliate and referenced when needed. We hope it comes in handy.

All three of these conditions can be treated with lifestyle changes, though the greatest impact will be on prediabetes and T2D. Nutrition and fitness improvement can lead to disease remission. This is because poor lifestyle choices are what led to the disease in the first place. A diet of meat, vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, little starch, and no sugar is a solid starting point for dietary improvements, especially for prediabetes. Those with T2D might need to add in some level of quantification. For instance, if there is a high degree of insulin resistance, macronutrients will have to be quantified, ensuring that carbohydrates stay low while fat and protein make up the rest of the caloric requirements. CrossFit suggests starting with 40% carbohydrates, 30% protein, and 30% fat when quantifying food intake. This carbohydrate intake might be too high, not allowing for the insulin reduction necessary for weight loss and reduced insulin resistance. Maintaining an isocaloric diet but adjusting macronutrients to meet 30% carbohydrates, 30% protein, and 40% fat, or even a lower carbohydrate and higher fat percentage, might be necessary to achieve the desired result.

All three of these conditions can be treated with lifestyle changes, though the greatest impact will be on prediabetes and T2D. Nutrition and fitness improvement can lead to disease remission. This is because poor lifestyle choices are what led to the disease in the first place. A diet of meat, vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, little starch, and no sugar is a solid starting point for dietary improvements, especially for prediabetes. Those with T2D might need to add in some level of quantification. For instance, if there is a high degree of insulin resistance, macronutrients will have to be quantified, ensuring that carbohydrates stay low while fat and protein make up the rest of the caloric requirements. CrossFit suggests starting with 40% carbohydrates, 30% protein, and 30% fat when quantifying food intake. This carbohydrate intake might be too high, not allowing for the insulin reduction necessary for weight loss and reduced insulin resistance. Maintaining an isocaloric diet but adjusting macronutrients to meet 30% carbohydrates, 30% protein, and 40% fat, or even a lower carbohydrate and higher fat percentage, might be necessary to achieve the desired result.