Drawings by Zac Pine -Insta: @coach_zip

At the CrossFit Level 1 and Level 2 Certificate Courses, you are introduced to common movement themes found in functional movements. One of the goals of utilizing these themes is to simplify our understanding of the points of performance and potential faults of a movement.

One such theme is that functional movements, done correctly, will have the athletes demonstrate midline stabilization. In this article, we will discuss what this means, why it’s crucial from a safety and performance standpoint, and where to look to assess it. We’ll also share examples of correct and poor execution and when deviations from a neutral spine are acceptable.

What Does Midline Stabilization Mean?

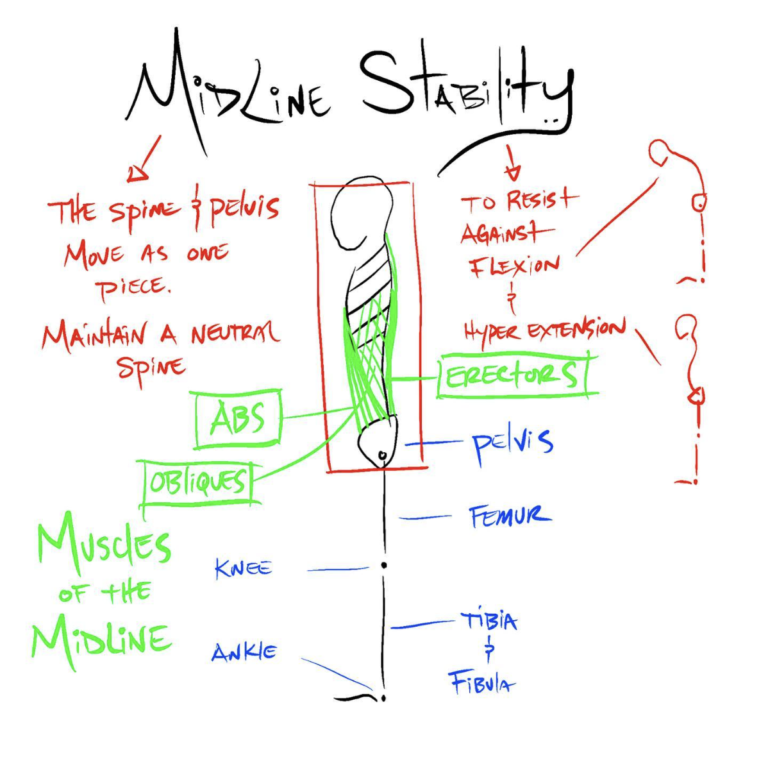

When viewing an individual from the profile, a reference line trisects the spine and bisects the pelvis, which we deem the “midline.” Midline stabilization is the ability to maintain rigidity, stability, and a lack of deviation from that line. In essence, it is the ability to maintain the natural S-curve of the spine and wed it to the pelvis when moving dynamically and/or with load.

Our definition of core strength is midline stabilization. The muscles surrounding the trunk — the abdominals, obliques, and erectors — are primarily responsible for maintaining this stabilization. When utilized appropriately, this musculature stabilizes the spine in every direction.

Why Is Midline Stability Important?

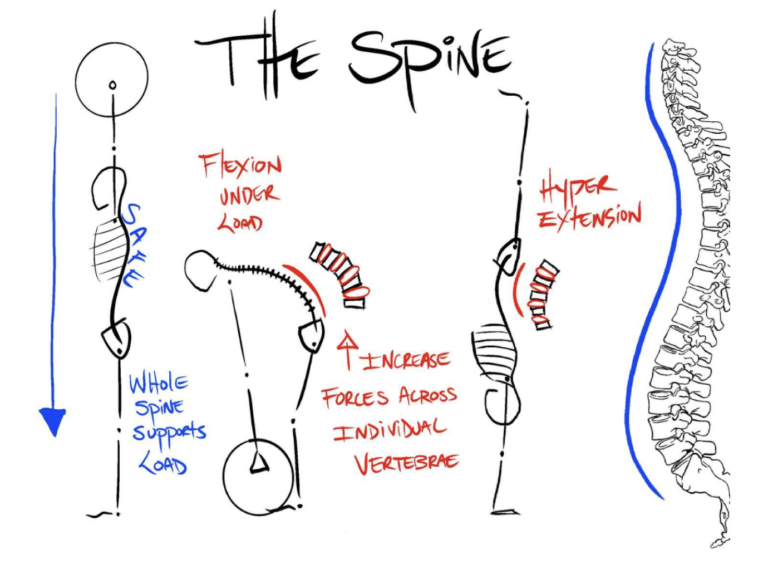

As a coach, you play a critical role in promoting safety and the performance benefits garnered through effectively teaching, seeing, and correcting for midline stabilization. Maintaining midline stabilization protects the spine, particularly the lumbar spine, from potentially hazardous shear forces that occur when stability is lost. The risk is increased when a loss of stabilization occurs during the dynamic phase of a movement when loaded.

Maintaining a neutral spine is not just for safety purposes. Midline stability also allows for more force and power to be expressed, allowing for the best transmission of force to the appendages and/or objects the athlete may be working with. For example, when performing a barbell push press, the legs and hips extend the force upward into the barbell through the torso. If the midline is not stable, optimal transfer of force will not occur. So, if you want to move more efficiently, lift heavier loads, etc., establishing midline stability is essential.

Where to Look?

Assessing an exercise for midline stabilization requires focusing on the athlete’s trunk and ensuring it meets the demands of the movement. This also requires knowing the demands of the trunk for the task at hand. For many movements, the trunk should remain neutral and unchanging from start to finish (deadlift), while in other movements, there may be acceptable movement about the spine (kipping pull-up).

Common Faults

Flexion of the Spine

Loss of midline stabilization occurs when the lumbar spine (L1-L5) moves into flexion, causing the normal concave curvature of the lower back to convex. Flexion of the spine is often seen with movements where the load is on the front side of the body (e.g., deadlift and front squat) and during movements requiring significant hip flexion (e.g., bottom of a squat, set-up position of a deadlift, etc.)

Hyperextension of the Spine

A loss of midline stability can also occur in the opposite manner as flexion by hyperextension of the spine. This fault occurs when the spine overextends excessively past neutral and generally lacks abdominal engagement. When this occurs, the spine has reached a range of motion potentially injurious to the spinal facet joints.

Hyperextension occurs primarily in overhead movements (e.g., shoulder press and handstand push-ups, excessive kipping motions, and even the initiation of a squat when the athlete overextends the lumbar curve by anteriorly rotating the pelvis).

Acceptable Deviations from Neutral Spine

The task at hand is the determining factor as to what should be occurring throughout the spine during the movement. There will be times when the task demands the spine move. For example, an AbMat sit-up or GHD sit-up will naturally have movement about the spine.

For movements where there is intentional movement of the spine for correct execution, it is necessary to assess if the degree of deviation is acceptable. For example, during a kipping motion, the spine moves as athletes transition between the arch and hollow positions. This movement is acceptable as long as the abdominals remain braced and engaged. However, if the athlete overarches and loses abdominal engagement — often accompanied by excessive leg and foot movement — it may indicate excessive and potentially problematic spinal motion.

Homework

Look at your programming for the week, analyze one movement from each workout, and ask the following questions:

- What movement (if any) should occur throughout the spine when the exercise is performed correctly?

- What primary fault(s) may occur at the spine during the movement?

- What is the root cause(s) of the fault?

- What is a corrective strategy for that fault?

Example: Toes-to-Bars

- Movement occurs at the spine as the athlete moves between arch and hollow positions when performing the kipping motion. It is also acceptable for the spine to flex when raising the toes to the bar.

- The primary fault is excessive hyperextension of the spine when the athlete moves into the arch position of the movement.

- The root cause of the fault is likely due to:

- Not being active in the abdominals in the arch phase of the movement.

- A lack of general strength, which causes the athlete to want extra momentum from an excessive kip.

- The athlete excessively bending their legs, which may contribute to overextension in the arch position.

- Corrective strategies for each respective fault include:

- Activating their abdominal muscles. You can cue the athlete to keep their abdominals tight or have them perform kip swings focusing on keeping tension in their abdominals.

- Strengthening their hip flexors. If the athlete lacks hip flexor strength to raise their toes to the bar, they can do additional work focusing on movements such as leg pike compressions, L-sit variations, and strict hanging leg/knee raises.

- Straightening their legs. You can cue athletes to keep their legs straight by tensing their quads to see if this assists with creating tension.

Want more on midline stability? Read Midline Stability, Part 1: More Than the Core, and Part 2: Power and Posture.

Eric O’Connor is a Content Developer and Seminar Staff Flowmaster for CrossFit’s Education Department and the co-creator of the former CrossFit Competitor’s Course. He has led over 400 seminars and has more than a decade of experience coaching at a CrossFit affiliate. He is a

Eric O’Connor is a Content Developer and Seminar Staff Flowmaster for CrossFit’s Education Department and the co-creator of the former CrossFit Competitor’s Course. He has led over 400 seminars and has more than a decade of experience coaching at a CrossFit affiliate. He is a