“There is increasing concern that in modern research false findings may be the majority or even the vast majority of published research claims.”

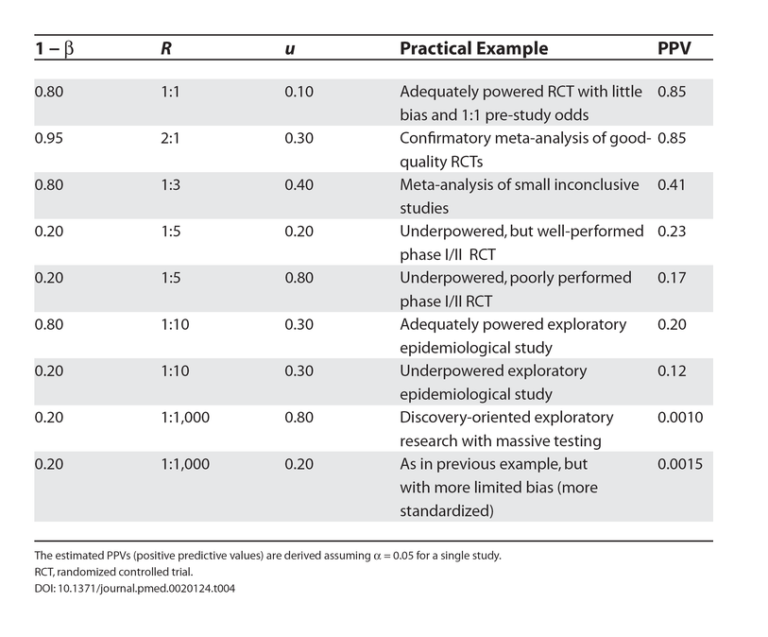

In this essay from 2005, Dr. John P.A. Ioannidis explains that the majority of modern “science” is unscientific. He notes that when a range of mitigating factors are accounted for, the majority of published “statistically significant” findings are likely to be untrue or unverifiable. Factors degrading the reliability of published research include small studies, small effect sizes, flexible study designs and financial incentives (which introduce bias), and a larger number of researchers working within a field.

Comments on Why Most Published Research Findings Are False

If you want to educate yourself on the bias of modern research the book Rigor Mortis by Richard Harris is a good resource.

I can’t help but think that the posting of articles like this on the site (with the respective comical picture) will have the unintended consequence of causing some to lose trust in their physicians/science, and that this could cause more harm than good. Please don’t misinterpret me, I think this article is great; The problem discussed is a huge problem, and I see it all the time- “my rationale for my recommendation is this paper, and look- ALL the p values are significant!”. But what is the intended goal of posting this here, in a site populated by many who are not trained in interpreting scientific literature? It seems at least possible for there to be unintended consequences that could be overall negative. I would be interested to hear what others think about this, or could perhaps enlighten me on what HQs thoughts are regarding this strategy. Is this a “fight fire with fire, bias with bias” approach? I am asking in the spirit of genuine interest, and would appreciate any and all feedback, and thanks in advance!

Spenser’s comment and question are good ones, a thoughtful variant of a reddit discussion today suggesting that these posts on the CrossFit site are making CrossFit “sound like a bunch of anti-vaxxers/climate change deniers.”

As a journalist who’s covered science, good and bad, for going on forty years and now the director of a non-profit that funds research and a consultant for CrossFit Health, I’ve always thought the average layperson (if such a person exists) should indeed have trust in their physicians and in science in general. But the catch, as Ioannidis points out in the article, is that a huge proportion of the latest research, the stuff we read about in the papers everyday, is simply incorrect or misinterpreted or meaningless. Twenty years ago, when I wrote an essay about this problem for Technology Review, I quoted the philosopher of science John Ziman suggesting that this is the case with 90 percent of the science published in the front-line journals (in physics, which is relatively reliable compared to medicine or nutrition and public health research), as it is in 10 percent of the science in the textbooks. Ziman then defined the process of science as the process of filtering through that front-line chaff to find the very little wheat that should then go into the textbooks.

Since I had spent much of my journalistic career documenting some of the more high-profile screw-ups in science, and since I was interviewing simultaneously some of the best experimental scientists in the world (theory is a different story entirely, and since they pretty much agreed with Ziman’s take, so did I. Good science, by which I mean establishing reliable knowledge about the universe, is simply very hard to do and most researchers fail to do pull it off. Even the best screw up regularly because they tend to work on the very hardest problems. All the easy stuff has been discovered, after all. Scientists are always working at the limits of what their technologies and their methodologies can test and observe and errors are a natural part of the process. The peer-review process does little to filter them out. That’s why the best scientists (experimentalists again) will talk about the need for humility in the scientific pursuit and why the Nobel Laureate Richard Feyman said the first principle of science is “you must not fool yourself and you’re the easiest person to fool.” (And, yes, I quote that a lot.) Ioannidis is more or less confirming Ziman’s assessment and Feynman’s first principle. It goes far beyond p values, as Ionnidis says in his paper, and it’s vitally important that everyone understand this. Since the publication process (and the funding process) tends to work against researchers who acknowledge in their papers that their results are likely to be wrong, meaningless or misinterpreted, the researchers themselves tend to hide this when they publish or talk to journalists. But it does seem to be true and we (all of us) should know it.

Now, we can make an argument that the lay person should be protected from this reality because it’s also the typical defense of scoundrels, frauds and shysters; that if they know this. they won’t trust scientists and physicians anymore, and the next thing you know we’ve all stopped vaccinating our children and are eating processed meats again. But I don’t think that position ultimately is defensible. The media has taken to reporting on the latest journal publications as though they’re news — as opposed to noise — and entire belief systems have been constructed about vitally important issues (nutrition and exercise physiology, most relevantly) that appear to be the scientific equivalents of houses of cards. Even the uninformed should have some idea what’s happening and why. It’s a tricky business, I admit, informing the public about how much of what they hear is likely to be wrong without also making those same folks skeptical of stuff that is very likely right and importantly so. As I said, I’ve been doing this for my entire career, and it’s still a tricky business. I still get considerable flak from some defenders of science while other defenders of science (and at least many very good scientists) see my work, or at least this kind of work, as vitally important and urge me on. I wish smarter people than me were doing it, but it has to be done.

So why is CrossFit posting these articles — exposing “many who are not trained in interpreting scientific literature” to the likelihood that much of that scientific literature is, well, coming to the wrong conclusions, meaningless or just out and out wrong? My take (speaking for myself and not HQ) is 1) it’s a messy job and someone has to do it. And 2) HQ thinks that as long as they’re helping CrossFitters get their bodies in ideal shape, they might as well give them the opportunity to work on their minds as well. One definition of science that I always liked, resonating with Feynman’s line, is that it is institutionalized skepticism. At some point we have to trust the scientists (and even our physicians) because they’re better suited to be knowledgeable about these issues than we are, but being reminded that skepticism is always in order, particularly about the latest results reported in the latest papers, is always a good thing. I think it’s a good exercise. Not quite deadlifts, but serving a different purpose.

As for the comical picture, that’s a matter of taste and I can’t comment.

Spenser, good question.

Reading articles such as this one has opened my eyes to some of the root problems currently existing in the medical field. As Gary mentioned so eloquently, it’s helping me get my mind in ideal shape. It’s making me think.

As a physician, I get no less than the 10 emails per day, with headlines such as “E-cigarettes help people quit smoking....” Huh?? (this is an actual title from a study reported on 1/30/2019). Where is this coming from, why does this not make any sense to me, and how am I supposed to use this in my medical practice? The topics of p hacking, bias, and academic advancements have really helped me understand why there are so many unscientific meaningless published research.

These findings come from journals such as the New England Journal of Medicine, are reported to us doctors via emails such as “AMA Morning Report”, and to the general public via the New York Times, Washington Post, morning talk shows, etc. Doctors (like me) really need to think before just regurgitating these “research titles” to patients. This article by Ioannidis is an eye opener....reminds me that I cannot read media titles. As a physician I need to read the articles, see if they are really scientific or just noise. And most of them are noise. Same for non physicians. Don’t mistake news for facts.

Now does that mean that all studies are false...no. It means I need to understand the methods (including study size), results (including effect size), and relevance of a study to be able to properly interpret it into my practice of medicine.

CrossFit is back to the basics.

Gary, thank you very much for the response; it has given me a lot to think about and to read up on; happy to have it as it gives me a better grounding in my own understanding. I agree, shielding lay people is ultimately not a defensible position. What you have said about the media is particularly true from my perspective. What quickly comes to mind for me are news articles that describe “breakthroughs” in incredibly complex disease state, such as alzheimer’s disease. They almost invariably are based on one article that offers some small piece of evidence in the scheme of human understanding. But breakthrough? The use of the word seems quite liberal. I think your opinion regarding the posting of these articles is sound. A healthy dose of skepticism is nearly always a good thing; more so with breaking news than with tertiary information that has withstood the test of time. I wonder what the mental equivalent of a deadlift would be? Reading Richard Feynman lectures?

Shakha, thank you for your input! I am incredibly sympathetic with what you have described; having to sort through the noise to find out what is truly beneficial for your patients must be exhausting at times. Glad to see that some are committed to taking the time to sift through the seemingly endless information to find meaningful evidence.

Having a p-value less than .05 is not really “statistically relevant”, and should not be a basis for assigning significance at all. By themselves, p-values calculated from a set of numbers and assuming a statistical model, are of limited value and often even worthless.

How, then, would you propose to determine the significance of any study? I'll admit that p-values aren't a perfect approach, but we must have some standardized way of separating the wheat from the chaff, so to speak.

This is not to say that results beyond a set p-value are not substantial, merely that they are not statistically significant.

I, like many eager medical students, was taught that a p value of less than 0.05 was the most powerful interpretive tool of a medical research article. How easy then for researchers to focus in on this one value, while essentially ignoring all others. It's little wonder that so many medical research articles boasting a "significant" p value were welcomed with such unbridled enthusiasm by young doctors in training.

Dr Thornton, so true! I remember doing my medical school research thesis, running as many possible statistical analysis that I could, and highlighting anything with a P < 0.05. And each highlight was like striking gold. It didn’t matter if it’s what we were looking for, or had any relevance to anything. What it meant...was getting a published paper, and a completed research assignment. We were taught this! We weren’t cheating, or hiding anything. It’s the way it was done.

Why Most Published Research Findings Are False

9