Placebos are used in clinical trials to demonstrate that an experimental drug is superior to the control or “inactive” pill (1). A placebo is usually defined as an “inert substance” (no effect), given to trial participants with the aim of making it impossible for them, and usually the researchers themselves, to know who is receiving an active or inactive therapy.

The exact contents of a placebo pill are often unknown; the “recipe” is not disclosed to the trial subjects, nor is it published in the peer-reviewed literature. Recently, the editor-in-chief of Clinical Therapeutics, Dr. Robert Shader, raised concerns when a 2017 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine injected one group of people with a monoclonal antibody (ocrelizumab) and the other group with a “matching placebo.”

But what was in the placebo? “Was it saline? Was it the same vehicle in which the monoclonal antibody was dissolved?” Shader rightly questioned. Researchers should provide the public with the exact ingredients contained within a placebo, but this is rarely the case.

Placebos can contain “excipients” such as chemicals, dyes, or allergens, which might unintentionally bring about symptoms in trial participants. For example, a study found 68% of people taking a cholesterol-lowering drug (cholestyramine) experienced gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., heartburn, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting). But then, so did 43% of people taking placebo. The study does not describe what was in the placebo pill, although, with such a high rate of side effects, it was unlikely to have been “inert.”

In trials of the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine, participants were told they were either receiving a “vaccine or placebo.” The vaccine manufacturer defines a placebo as an “inactive pill, liquid, or powder that has no treatment value.”

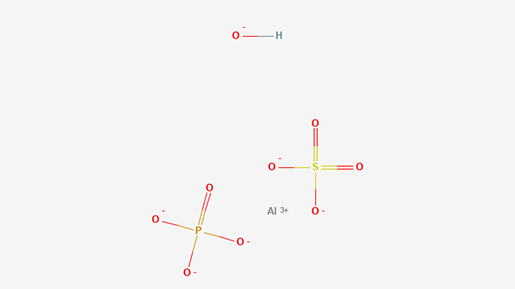

However, participants in the placebo group did not receive an inactive substance of no treatment value. “Instead,” RIAT researchers state in the BMJ, “they received an injection containing amorphous aluminium hydroxyphosphate (AAHS), a proprietary adjuvant system used in the Gardasil vaccine to boost immune response.”

Aluminium hydroxyphosphate (AAHS) structure

This raises two serious issues. First, the placebo is not inert, so the choice of adjuvant (AAHS) in the so-called “placebo control” complicates the interpretation of efficacy and safety results in trials, especially because AAHS is reported to have a harm profile.

Second, it challenges whether the researchers obtained informed consent from the participants in the clinical trial. The concept of informed consent is embedded in the principles of the Nuremberg Code, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Belmont Report to protect rights and welfare of human research subjects.

“If trial participants were told they could receive ‘placebo’ — widely defined as an ‘inactive’ or ‘inert’ substance — without being informed of all non-inert contents of the control arm injection, this raises ethical questions about trial conduct as well,” say RIAT researchers analyzing the trial documents.

Drug regulators such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA), Health Canada, or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have access to this information, and for a long while, the information was protected as commercially confidential.

But changes in policy surrounding transparency have improved since the EMA, in 2010, decided it would allow independent investigators to obtain access to regulatory documents and other clinical data.

The process of obtaining regulatory documents, however, is by no means straightforward. In fact, it is often complicated and time consuming. I have made multiple appeals to a European drug regulator (Medicines Evaluation Board) to obtain information (Certificate of Analysis) regarding the ingredients of a placebo used in a controversial statin study (JUPITER trial), but so far, they have fallen on deaf ears. So, too, have my requests to the trial’s lead investigator, Dr. Paul Ridker.

Medical journals will need to take responsibility and insist that published papers report on the methodological details of “inactive” placebos. Recently, Shader of Clinical Therapeutics stated, “It will no longer be sufficient to simply indicate that a placebo was used.”

“We will require that a full description of any placebo or matched control used in a clinical trial be given in the Methods section. This means that color; type (capsule or pill or liquid); contents (e.g, lactose), including dyes; taste (if there is any); and packaging (e.g, double-dummy) must be noted,” he stated. “We are instituting this change as part of our ongoing effort to facilitate replication of findings from trials. All too often this valuable information is omitted from published trial results.”

Failing to accurately match a placebo to the experimental drug can result in underreporting of harms or misleading trial outcomes. Not only is it important to foster public confidence in therapies that rely on comprehensive and independent assessments, it is an ethical and legal requirement to provide fully informed consent for research involving human participants.

Additional Reading

Dr. Maryanne Demasi is a well-known investigative journalist whose work on scientific documentaries has been praised by the National Press Club of Australia for exhibiting “excellence in health journalism.”

Demasi earned a Ph.D. in rheumatology from the University of Adelaide in 2004. She currently works as a researcher for the Nordic Cochrane Centre.

Notes

- Sometimes researchers deliberately use an “active” placebo to mimic the side effects of a drug in cases where the side effects are well known (e.g., dry mouth with antidepressants).