Editor’s Note: Dr. Paul Rosch passed away on Feb. 26, 2020, before publication of this profile. Author Dr. Maryanne Demasi has since included the following note:

I have been a long-time admirer of Paul J. Rosch. Recently, we had a memorable exchange while I was interviewing him for a profile piece.

He was calm, full of wisdom, and generous with his time. He spoke with authority and often recited the words of great philosophers during our communications. Paul was a skeptic in the true sense of the word, always questioning the status quo, which is why it was so fitting that he dedicated his life to science.

As a scientist, he was razor sharp and unrelenting about the pitfalls of modern medicine. He was well known for his work on exposing the fallacies of the lipid and diet-heart hypotheses, although he was unpretentious about his contribution, often giving credit to others.

Throughout his decorated career, Paul’s enthusiasm to make a difference never waned, as demonstrated by his prolific work in scientific publications, books, and TV interviews. Paul inspired a generation of scientists and lay people to challenge established views.

Despite his critical analysis of medical research, he was optimistic about the positive change he observed in his later years. He was encouraged to see that many of the scientific “heretics” he spoke of were finally being vindicated.

I regret not having the opportunity to meet him in person, to shake the hand of the man I greatly admired. But even with the impersonal nature of conversing over digital technology, his warmth shone through.

I am deeply saddened by the news of his passing. RIP, Paul J. Rosch.

How did we get the cholesterol theory of heart disease so wrong? It’s a question many of us have been asking ourselves, but the response from Dr. Paul J. Rosch is unwavering.

“So much of what is published has been motivated by money,” he says. “And the fallacious hypothesis that a high-fat diet leads to high cholesterol, atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease is a prime example.”

Rosch is a Clinical Professor of Medicine at New York Medical College and Chair of The American Institute of Stress. In the early 80s, he organized a series of lectures on the fallacies of the cholesterol hypothesis, featuring leading authorities from all over the world.

Rosch knows all too well that being a pioneer of new ideas is fraught with risk. “Those who challenge established ideas are punished or persecuted,” he says. And who could forget the skullduggery unleashed upon legendary cholesterol skeptic Dr. Uffe Ravnskov following the publication of his book.

“Uffe’s conclusions were so contrary to the prevailing dogma that his book was actually burned on a Finnish TV program by cholesterol proponents,” Rosch says with disbelief. “And yet, his critics refused to debate him on TV.”

Rosch laments the reluctance of the medical establishment to vigorously contest new theories. Critics who are cowardly and crooked are quick to shoot the messenger while simultaneously refusing to publicly debate the science or provide access to the raw data used to make false claims.

To honor Ravnskov’s seminal work in disputing the cholesterol hypothesis, Rosch decided to convene several distinguished researchers to co-author a book called Fat and Cholesterol Don’t Cause Heart Attacks and Statins are not the Solution. A sequel to this, called Lipid Lunacy, Dietary Delusions and What Really Causes Heart Disease, is scheduled for release in July 2020.

Rosch gives recognition to a list of scientists who spoke out and subsequently endured public castigation and career intimidation. Aside from Ravnskov, he includes George V. Mann, Kilmer McCulley, Tim Noakes, Gary Fettke, Peter Gøtzsche, and yours truly. On a positive note, however, Rosch says, “Most of the presumed heretics have been vindicated, so there is some light at the end of the tunnel.”

Rosch says proponents of the cholesterol theory have refined the art of repeating a mantra until it becomes fact: “If you repeat anything often enough, it is perceived as the truth, regardless of how erroneous or ridiculous it is,” Rosch says. “As William James, the father of modern psychology noted, ‘There’s nothing so absurd that if you repeat it often enough, people will believe it,’” he adds.

In fact, Rosch has a propensity to cite former luminaries when explaining why many scientific fallacies have persisted. “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed, second, it is violently opposed, and third, it is accepted as self-evident,” he says, quoting Arthur Schopenhauer.

In 1985, the American Society for Contemporary Medicine and Surgery awarded Rosch for his contributions to our understanding of stress, health, and disease. The president of that society was renowned heart surgeon Dr. Michael DeBakey, a pioneer of surgical advancements in cardiology.

DeBakey took an interest in Rosch’s work after observing and analyzing thousands of his own patients’ arteries. DeBakey came to the same conclusion that cholesterol levels were not related to the progression of atherosclerosis, since people with low cholesterol levels were just as likely as others to develop plaque.

When asked about the unscrupulous practices of the drug industry, Rosch attributes blame to the direct-to-consumer advertising in the U.S. He argues that it’s often deceptive — even fraudulent — and refers to the famous TV ad by Pfizer that featured an apparently credible and affable doctor named Robert Jarvik.

“Jarvik was introduced as a cardiologist and as the inventor of the artificial heart,” Rosch says. “But in reality, Dr. Jarvik was not a cardiologist, he had never been licensed as a physician, nor could he legally prescribe any drug … and he did not even invent the artificial heart.”

Pfizer pulled the ad in 2008 following a Congressional investigation into bogus ads and concerns that Jarvik was dispensing medical advice without a license. But for the millions of consumers who saw the ad, it was too late. A report showed that over 90% of people who saw the ad believed it was credible and accurate, and over a third of people taking a statin from a competing company said they would likely ask to change to Lipitor.

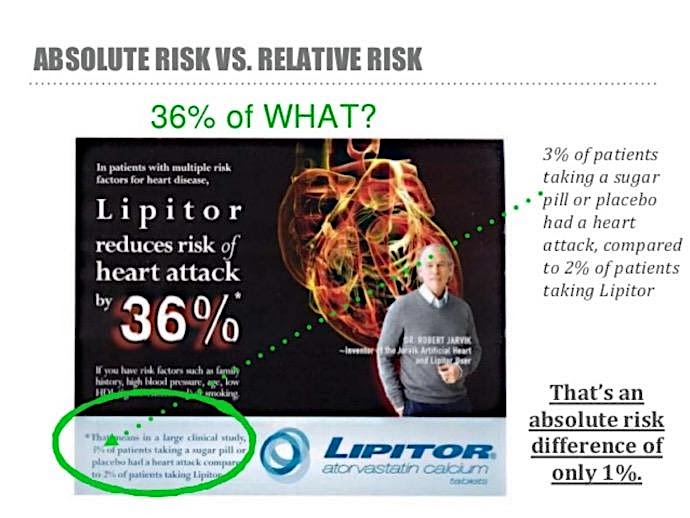

Pfizer also widely published an ad boasting a 36% relative risk reduction in heart attacks by taking Lipitor. But closely inspecting the fine print, you can see the absolute risk reduction was only 1%.

Pfizer also widely published an ad boasting a 36% relative risk reduction in heart attacks by taking Lipitor. But closely inspecting the fine print, you can see the absolute risk reduction was only 1%.

“How many people would take Lipitor if they knew that its likelihood of preventing a heart attack was one in 100 if they took it for 10 years?” Rosch asks. “And this was only for those individuals at high risk.”

In 2006, Pfizer spent over $258 million marketing Lipitor. And it paid off. That year alone, the drug generated $13 billion in sales and became the most profitable drug in the history of medicine.

When Pfizer was fined $2.3 billion in 2009 for fraudulent advertising, which at the time was the largest such criminal fine ever imposed in the U.S., it barely put a dent in profits. Despite Lipitor’s patent expiring eight years ago, it is on track to generate close to $2 billion in revenue this year.

Manufacturers of statins, low-fat foods, and lipid testing devices have formed a powerful coalition that Rosch refers to as the “cholesterol cartel.” He says it has stifled any opposition to the status quo and prevented much needed research in other areas of cardiovascular disease prevention.

So, if cholesterol doesn’t cause heart disease, then what does?

Rosch has published prolifically in this area, writing numerous books and articles and sitting for interviews on national TV. According to Rosch, coronary heart disease has no causa vera, or true cause, without which it would not occur.

However, he says stress (physical, emotional, or environmental) is a significant factor, as well as elevated blood homocysteine and factors that accelerate blood clotting.

Rosch says the future of disease treatment may well lie in bioelectromagnetic therapies, a topic about which he has previously published. These therapies are not only for heart disease but depression, epilepsy, and other degenerative and neurological disorders, he notes.

As far as moving on from the cholesterol hypothesis, “a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it,” Rosch says, quoting German physicist Max Planck.

Dr. Maryanne Demasi is a well-known investigative journalist whose work on scientific documentaries has been praised by the National Press Club of Australia for exhibiting “excellence in health journalism.”

Demasi earned a Ph.D. in rheumatology from the University of Adelaide in 2004. She currently works as a researcher for the Nordic Cochrane Centre.

Comments on In Conversation With Paul J. Rosch

Rosch is a big loss for humanity. It is important for the public to recognize that most of the "scientific" research in favor of cholesterol-lowering statins is flawed and fraudulent (eg, read the work of Rosch or Uffe Ravnskov, MD, PhD).

The most reliable evidence has long tied statin use with memory problems, muscle disorders, liver damage, cataracts, nerve damage, arterial calcification, pancreatitis, erectile dysfunction, brain dysfunction, diabetes, and with an increased risk of cancer and higher mortality. There are practically no, or only marginal, benefits from these toxic drugs.

The physiological mechanisms of how statins do serious damage are also well understood, such as by their impairment of oxidative cell metabolism, the increase in inflammation and cell destruction, the lowering of cholesterol and sex hormone production, the promotion of pancreatic injury, etc. - rather thoroughly explained in this scholarly article by a published author of the Orthomolecular Medicine News organization, on how statins, and a cholesterol-lowering popular diet pill advertised by Dr. Oz, promote diabetes at https://www.supplements-and-health.com/garcinia-cambogia-side-effects.html - look at Figure 7 to see how irrational it is to block the production of cholesterol!

Yet despite of the existence of that scientific knowledge, the medical business and the public health authorities keep ignoring it and, for example, continue to recommend statins to diabetics and make claims that they have a low risk profile despite that they are also significantly linked to cancer and higher mortality (just look at the propaganda put out by the Mayo clinic on statin drugs: "the risk of life-threatening side effects from statins is very low").

And because of such medical propaganda, few people are aware that the medical claims of benefits of statins are mostly based on junk studies conducted by people with vested interests. And, logically, it's mostly the corporate medical business and other people with similar vested interests tied to it (eg, mouthpieces, hacks) who promote the alleged value of these highly lucrative products.

Also, older people with HIGH cholesterol live longer than those with low cholesterol levels (see above mentioned article for numerous scientific study references confirming this).

Because the cholesterol-heart disease theory, or rather medical dogma, is wrong, the use of statins is also wrong by logical extension.

So the real truth is that statins have almost no real benefit in the very vast majority of users. They do more harm than good (read the cited book by Rosch and others, or Uffe Ravnskov's "The Cholesterol Myths" and Malcolm Kendrick's "The Great Cholesterol Con"). It's one of many "scientific" scams of the criminal mainstream medical business.

Sam,

You are right. Great response.

In my opinion, it is medical malpractice, amoral and unethical to be in any way associated with the prescription and/or delivery of statin drugs.

In Conversation With Paul J. Rosch

2