Stepping on the scale is a source of anxiety and frustration for many people. Many nutritionists recommend weigh-ins only once a month or less out of concern for their client’s scale anxiety. Yet these same nutritionists will advise their clients to count calories. From the outside, dieters appear to be either living out their childhood dreams of becoming accountants or following a plan so precise that a single extra slice of bread could throw the whole thing off.

A calorie is a unit of energy. Our bodies convert the chemical energy of food — mostly in the form of carbohydrates, protein, and fat — into thermal energy (body heat) and kinetic energy (activity). Calorie counting represents an attempt to balance the chemical energy we ingest with the thermal and kinetic energy we expend.

We know the caloric content of the basic macronutrients:

- 9 calories per gram of fat

- 7 calories per gram of alcohol

- 4 calories per gram of carbohydrates and protein

- 2 calories per gram of fiber

The number of calories in any food can be measured with great accuracy by a bomb calorimeter (1). Unfortunately, these scientific instruments do not accurately model the workings of the digestive system, which breaks down foods using mechanical effort, acids, enzymes, and bacteria.

Some of the calories in food are expended in the process of digestion. High-glycemic carbs require very little digestive effort. Protein and fiber are much more taxing, especially when consumed raw. Cooking (and other methods of processing) breaks down complex carbohydrates, softens the cell walls of plants, and denatures proteins. Food-borne pathogens normally fought off by your immune system are instead killed in the heat of the cooking process. Cooking does much of the energy-intensive work of digestion before a piece of food even reaches your mouth. As a result, we get more calories from cooked foods than raw foods.

There is also substantial variation in what percentage of calories are fully digested and utilized by the body. Almonds nominally contain 170 calories per serving, but scientists found 41 of these calories in the urine and feces of the people who ate them. Only 129 calories (76%) remained in the body. Bits of undigested food like sesame seeds, peanuts, and corn can pass through us perfectly intact, taking their calories with them.

To relabel everything sold in the grocery store to account for cooking and digestion would require a massive scientific and political effort — not to mention digging through lots of excrement, literally and metaphorically.

Packaged foods present us with even more accounting irregularities. Food labeling is regulated by the FDA, which allows a range of plus or minus 20% for the total calories listed on the box.

This would not be a big deal if the errors in one food were offset by the next. However, it is the food producers’ responsibility to self-report the caloric content of their products. Errors trend toward more calories than indicated, so the miscalculations don’t cancel each other out — they stack up. One study on 24 popular snack products reported 4.3% more total calories and 7.7% more carbohydrates than listed on the labels.

Attempting to measure calories taken in is a mess, but calories out is no picnic either. A research study out of Stanford University tested the accuracy of seven popular wearable fitness trackers. They were off by up to 93%. The best performing device was 27% inaccurate.

When people see the calorie readouts on fitness equipment, they are typically shocked by how few calories were burned during their workout. This is because activity accounts for only a small proportion of a typical person’s total daily energy expenditure (2). For instance, one online calculator offers the following estimates for daily energy expenditure from activity alone:

- 17% for a sedentary office worker

- 27% for a light exerciser (exercising 1-2 days per week)

- 35% for a moderate exerciser (exercising 3-5 days per week)

- 42% for a heavy exerciser (exercising 6-7 days per week)

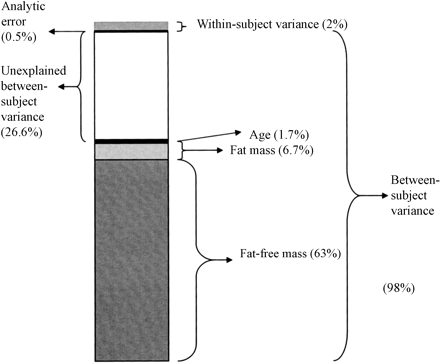

Most energy goes toward keeping the body warm and functioning. This is called your basal metabolic rate (BMR). It covers everything from building cells and tissues to breathing, pumping blood, and keeping the brain functioning. Your brain alone consumes about 20% of your energy. Formulas, like Harris-Benedict, estimate your BMR based on sex, age, weight, and height. However, body composition, ethnicity, internal temperature, and genetic factors can throw off this estimate. Studies have shown 26% of the variance in BMR between different people is unaccounted for by the factors mentioned above (3).

People on severely calorie-restricted diets typically lose less weight than expected. This is because when the body enters starvation mode, body temperature can drop by several degrees. In the Biosphere II experiment, eight people were sealed into a closed, artificial environment for two years (4). Body mass dropped by 18% and 10% in the men and women, respectively. Under these conditions, their body temperatures dropped to 96-97℉ and sometimes lower. The thermometers were not calibrated to measure below 96℉, so it’s not known how low their body temperatures dropped. Starvation is not only unnecessary for weight loss, but it can throw off your calorie counting, too.

Another problem with counting calories for weight loss is that the only calories that count are the ones you remember. People frequently forget to log what they eat, and this means they undercount by 12-25% (5). It would be unusual for someone to report a ribeye steak they never ate but very likely to forget a candy bar eaten in a hurry. Any nutrition research based on survey data is subject to these flaws. A paper by S. Stanley Young and Alan Karr compared the claims of 52 observational studies with the results of randomized control trials. The observational studies failed to replicate a single claim.

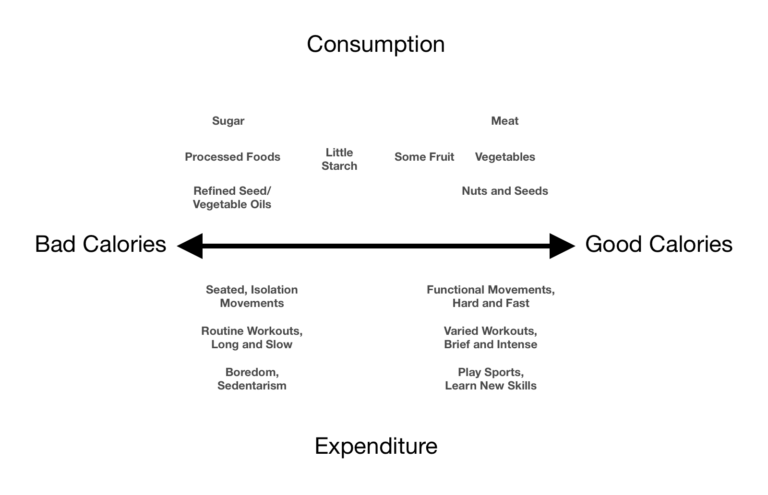

Once you have factored in all of these sources of error, it is clear calorie counting is not an effective method for promoting weight loss or improving overall health. However, I’m not advocating flying with a blindfold on. It’s highly recommended to plan meals based on the specific diet you are following. If you are on a keto diet, tracking your carbohydrate intake is essential. The Zone diet uses the block system, which makes meal planning easier. Some very analytical people who are not even diabetic are now wearing continuous glucose monitors to learn how specific foods and activities affect their blood sugar. On the activity side, counting every heartbeat and step you take is mostly just noise. It’s much smarter to track whether your WOD results are heading in the right direction. Trying to achieve weight loss by creating a precisely measured calorie deficit — in spite of a suboptimal diet and training — is a fool’s errand.

Eating sugary junk food will spike your insulin and drive fat into storage. Low-intensity exercise is likely to make you hungry for even more carbs. Gary Taubes argues in Good Calories, Bad Calories that fat deposition is regulated by hormones, not excess calories. It is much better to focus on the quality of your calories. Eat high-quality foods and exercise with functional movements at high intensity. Your body’s hormonal milieu will improve, and this will drive favorable changes in body composition.

Additional Reading

- The Quality of Calories: Competing Paradigms of Obesity Pathogenesis, a Historical Perspective

Science Reveals Why Calorie Counts Are All Wrong - Fitness Trackers Accurately Measure Heart Rate But Not Calories Burned

- Factors Influencing Variation in Basal Metabolic Rate Include Fat-Free Mass, Fat Mass, Age, and Circulating Thyroxine But Not Sex, Circulating Leptin, or Triiodothyronine

- Substantial and Sustained Improvements in Blood Pressure, Weight and Lipid Profiles From a Carbohydrate Restricted Diet

- Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance: Underlying Causes and Modification by Exercise Training

Notes

- To better understand the differences between the human body and a bomb calorimeter, you can do no better than this speech given by Zoë Harcombe at the Public Health Collaboration conference in 2018: Kettles, Calories & Energy Balance: What Went Wrong?

- The following estimates were calculated based on a 30-year-old, 150-lb. male.

- Factors influencing variation in basal metabolic rate include fat-free mass, fat mass, age, and circulating thyroxine but not sex, circulating leptin, or triiodothyronine.

- Physiologic Changes in Humans Subjected to Severe, Selective Calorie Restriction for Two Years in Biosphere 2: Health, Aging, and Toxicological Perspectives

- Estimated 12-25% undercounting is based on 24-hour dietary recall compared to doubly labeled water. Food frequency questionnaires are even less accurate, underreporting calories by 24-33%. See Addressing Current Criticism Regarding the Value of Self-Report Dietary Data.