In this extended review, Vladimir Subbotin argues that, contrary to a widely accepted hypothesis, coronary atherosclerosis begins not because of dysfunction in the arterial lumen but rather in the vasa vasorum.

Subbotin summarizes the widely accepted understanding of atherosclerosis as follows:

- Atherosclerosis is a systemic disease.

- Atherosclerosis is initiated via inflammation and high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C).

- Atherosclerosis progresses via lipid and macrophage deposition from the coronary lumen into the arterial wall, leading to plaque formation.

He observes problems inherent to each of these three assumptions.

First, atherosclerosis does not seem to be a systemic disease because it does not affect the entire arterial bed equally—it exclusively affects large muscular arteries and some elastic arteries.

Second, studies testing both the raising and lowering of LDL and inflammation have not directly affected risk of coronary atherosclerosis in a way that would be expected if these factors were directly causal. For example, lowering LDL levels by 60-70% reduces the risk of, but does not prevent, atherosclerosis. (Statins, for example, reduce LDL-C significantly in nearly 100% of subjects but will prevent a heart attack in only 30-40% of those with high baseline cholesterol.) Subbotin notes, therefore, that “unfortunately, it appears that the scientific and medical communities are focusing on and emphasizing biomarkers that can predict risk, without proof that these biomarkers cause the risk.”

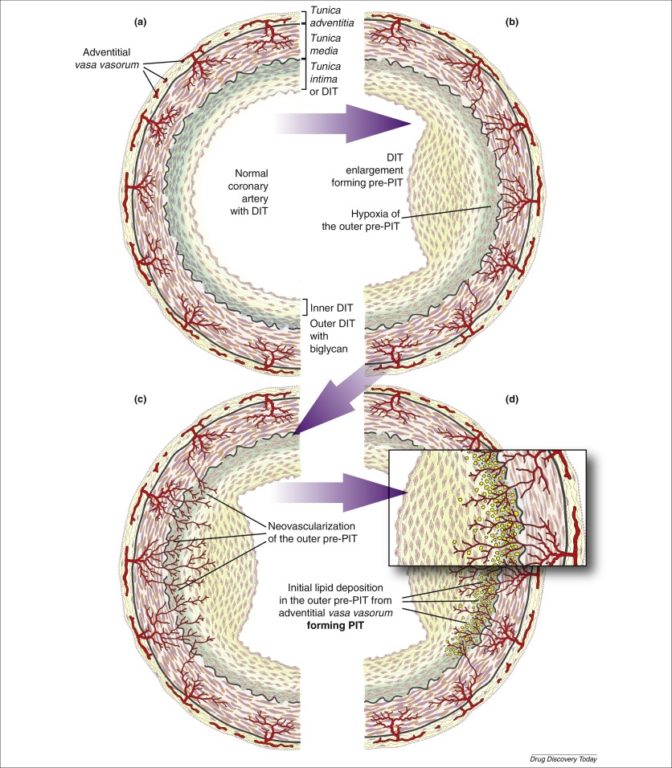

Third, the physiology of lipid deposition makes a lumen-centric deposition pathway seem unlikely. The “outer lipid deposition paradox” describes the observed growth of lipid plaques—fatty streaks first begin to form at the outer edge of the coronary intima, not the interior, and then gradually progress toward the center of the vessel. The widely accepted mechanism is that lipoproteins (and other plaque-forming factors) diffuse through the coronary intima before being bound by biglycan at the outer intimal edge. However, the coronary intima (in contrast to many textbook diagrams, which show it as a thin, acellular layer) is a thick, complex body composed of multiple cellular layers, which thicken over time. With this perspective, it becomes increasingly hard to believe this sort of diffusion can occur. As Subbotin puts it, “The probability of diffusion to this depth of some blood constituents including LDL-C particles is very low,” particularly since an alternative hypothesis exists.

Subbotin’s alternative hypothesis is that lipid deposition and other elements of plaque formation begin from the vasa vasorum. As the intima thickens, it becomes increasingly vascularized by the development of vasa vasorum on the outer arterial wall. These newly formed vessels are highly permeable. The vasa vasorum allows LDL-C particles and other plaque-forming elements to access the outer intima directly, exposing cholesterol to biglycan—to which it then binds, beginning the atherosclerotic progression.

This alternative hypothesis implies that the necessary step for the development of atherosclerosis is intimal thickening and the compensatory infiltration of the thickened intima by vasa vasorum. Specifically, arterial thickening leads to ischemia (i.e., loss of blood flow) of outer arterial cells, which leads to vasa vasorum formation, which then allows cholesterol infiltration into the arterial wall. Thus, the primary cause of atherosclerosis is intimal thickening and vascularization of the outer intima.

This alternative hypothesis implies that the necessary step for the development of atherosclerosis is intimal thickening and the compensatory infiltration of the thickened intima by vasa vasorum. Specifically, arterial thickening leads to ischemia (i.e., loss of blood flow) of outer arterial cells, which leads to vasa vasorum formation, which then allows cholesterol infiltration into the arterial wall. Thus, the primary cause of atherosclerosis is intimal thickening and vascularization of the outer intima.

Subbotin acknowledges that this hypothesis does not offer “an immediate solution.” Intimal thickening and its subsequent neovascularization by vasa vasorum are difficult to target systemically without negative side effects. He proposes, instead, that this alternative hypothesis will lead to more effective future research into the cause, prevention, and treatment of atherosclerosis.