This 2019 trial evaluated the impact of processed food in the diet on caloric intake, independent of other factors.

Twenty subjects were housed in the NIH Clinical Center for four weeks. For two weeks, they ate a diet consisting almost entirely of highly processed foods (i.e., packaged foods available at a typical grocery store). For the remaining two weeks, they ate an unprocessed diet. The order of the diets was randomized for each subject. Besides the level of food processing, these diets were as similar as possible; both contained calorie breakdowns of ~48% carbohydrate, ~37% fat, and 14-16% protein and had similar energy density, sodium, and fiber content. The ultra-processed diet did, however, have higher levels of sugar, higher non-beverage energy density (calories per gram of food), and lower levels of insoluble fiber than the unprocessed diet.

All food was prepared by study staff, and subjects were monitored 24/7. Subjects were fed three daily meals and had unlimited access to snacks. The primary outcome of the study was the number of calories subjects chose to eat under these conditions.

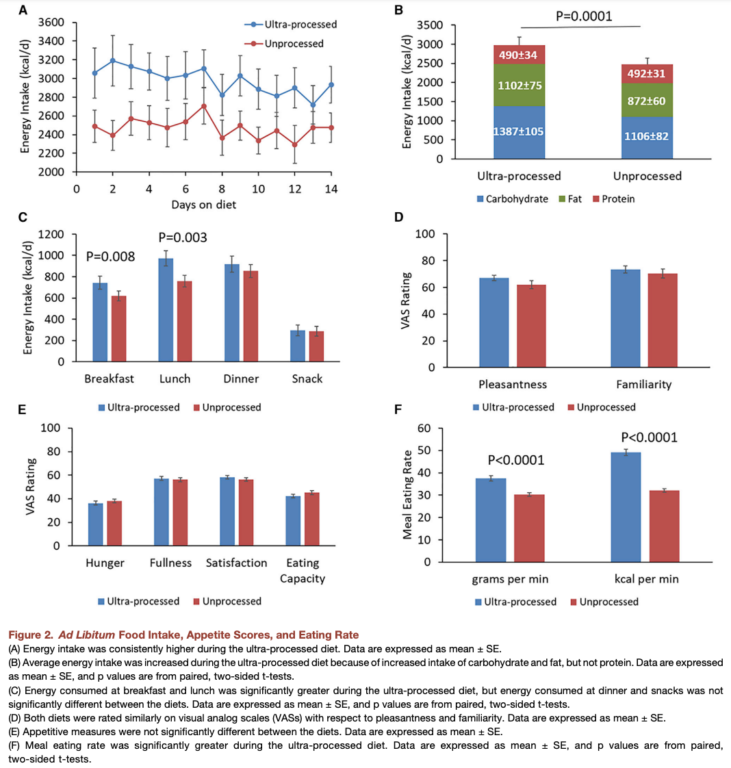

Subjects on the ultra-processed diet consumed an average of 2,979 daily calories, while subjects consuming an unprocessed diet consumed 2,470 — that is, subjects consumed an average of 509 calories (508 ± 106 kcal/day; p = 0.0001) per day more on an ultra-processed diet than an unprocessed diet. The number of calories from protein was nearly identical between diets, but subjects consumed 230 additional calories from fat and 281 additional calories from carbohydrate on an ultra-processed diet compared to an unprocessed diet. Energy intake was fairly consistent over the 14-day periods across both diets. These intake data are shown in Figure 2A and 2B below.

This study was designed to test whether processed food inherently leads to greater caloric intake than unprocessed food, independent of other dietary factors — in other words, whether a diet with the same levels of carbohydrates, fats, protein, sugars, and other nutrients will lead to greater calorie intake if those foods are processed. The perspective that caloric intake may increase as a result of food processing contrasts with a nutrient-centric view that argues processed foods are associated with obesity for reasons explained by their nutrient profile — i.e., they’re higher in carbohydrates, fats and sugars, lower in protein and fiber, etc. The authors concluded the study’s results were consistent with the former perspective, and two otherwise identical diets differing only in the degree of food processing led to significantly different levels of calorie intake.

In a comment also published by the journal, Dr. David Ludwig et al. caution against overinterpreting these results. They note that despite attempts to match the composition of the processed and unprocessed diets, subjects eating a processed diet actually ate more carbohydrate, sugar, saturated fat, and sodium, and consumed a diet with much higher energy density (i.e., more calories per gram of food) than subjects eating an unprocessed diet. Previous data has shown diets with higher energy density increase short-term but not long-term caloric intake, so the observed increase in calories consumed may not hold over weeks to months. They argue it is premature to use these results to support any health claims until they are replicated in longer-term studies.

In the final comment reviewed here, lead author Kevin Hall responds to Ludwig et al.’s critique, correcting some factual errors in the previous response while arguing short-term studies, while flawed, are able to precisely measure food intake and its metabolic consequences in a way longer-term studies cannot. He argues long-term observational research has consistently linked ultra-processed diets to poor health outcomes and reducing processed food intake ought to be a universal goal.