The heart’s structure affects the entire cardiovascular system. It pumps blood out through arteries and receives blood through veins (the pulmonary artery and pulmonary vein are exceptions).

Arteries

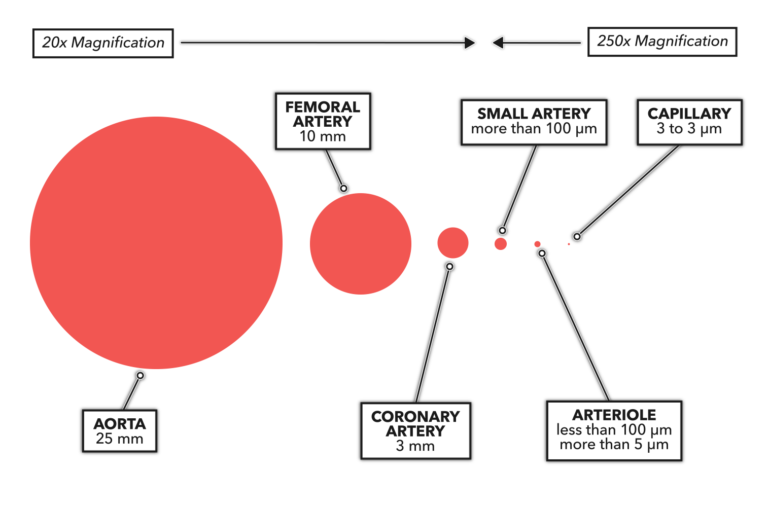

Arteries carry oxygenated blood away from the heart. They can be huge, larger in diameter than your thumb, as in the case of the aorta. They can be small, down to around 100 micrometers in diameter (there are 25,500 micrometers in an inch); any vessels smaller than that are called arterioles. The last vessel type on the arterial side includes extremely miniscule vessels called capillaries, generally only a few micrometers in diameter. The smallest capillaries are big enough to allow passage of only one erythrocyte (red blood cell) at a time.

Figure 1: Comparative schematic of arteries and related circulatory vessels. The size of the circles indicates the estimated relative dimension of each type of vessel. Smaller vessels cannot be seen with the naked eye and are represented at the magnification needed to visualize them graphically.

Arterial walls are thick. The aorta’s walls make up about 10% of its diameter and are about 2.0 to 2.5 millimeters thick. Small arterial walls make up about 20 to 25% of an artery’s diameter and are about 2.0 to 2.5 micrometers thick. Capillary walls form about 5% of capillary diameter.

Arteries and arterioles are stratified structurally into three layers: tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica externa (also called the tunica adventitia). Within those layers is a specific type of muscle — smooth muscle — that aids in directional flow. Arteries and arterioles also contain an extendable and elastic form of connective tissue within their walls. The innermost layer, the tunica intima, is composed of endothelial cells (small cells) and elastic connective tissue elements. The tunica media (middle layer) consists mostly of smooth muscle cells. The tunica externa (exterior layer) is made up of connective tissue with scattered smooth muscle cells.

Veins

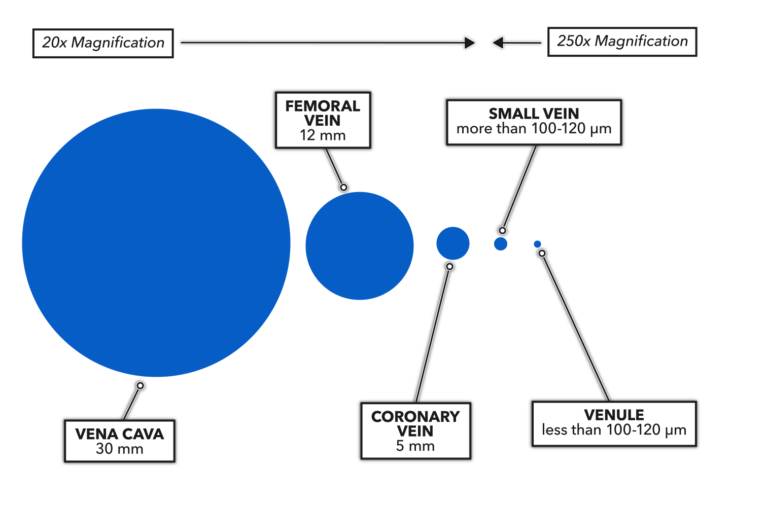

Veins carry deoxygenated blood toward the heart and occur in pairs with arteries. A vein that pairs with an artery at any given location is a little larger in diameter than the artery, and its walls are about half to two-thirds as thick.

Figure 2: Comparative schematic of veins and related circulatory vessels. The size of the circles indicates the estimated relative dimension of each type of vessel. Smaller vessels cannot be seen with the naked eye and are represented at the magnification needed to visualize them graphically.

Veins are also stratified but more like simple tubes, lacking the more active musculature of arteries. The tunica media and externa are less extensive in veins. The numerous one-way valves that prevent the backflow of blood are an element that is unique to veins.

Blood exiting the heart has the highest pressure, the downstream arteries have the next highest, veins have lower pressures, and blood entering the heart has the lowest pressure. Blood flow follows the pressure drop: Larger-diameter venous vessels have a lower pressure inside them, which allows blood from higher-pressure arterial vessels to flow into them. The right atrium has the lowest pressure of all the circulatory elements, so the venous blood continues to flow down the pressure gradient into the right atrium, where it begins the cardiac pressure cycle again.

Blood vessels are adaptable to stress. If there is hypoxic stress (low oxygen content present) that results in tissue hypoxemia (low oxygen in the tissue), a cascade of local hormonal and anabolic events occurs that produces new capillaries and new arterioles. This process is called angiogenesis and is considered to be an endurance-friendly anatomical adaptation, improving the body’s capacity to deliver oxygen to working skeletal muscle.