A specialized set of cells within the walls of the heart conduct and direct electrical impulses from atria to ventricles. The arrangement of these cells is both compartmentalized and contiguous in order to organize electrical activity and induce a sequential muscle contraction, squeezing blood through the heart without allowing backflow. The electrical activity driving muscle contraction can be recorded and visualized. Virtually everyone is familiar with this technology — it’s the electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) you have as part of your physical checkup or see on your favorite medical shows.

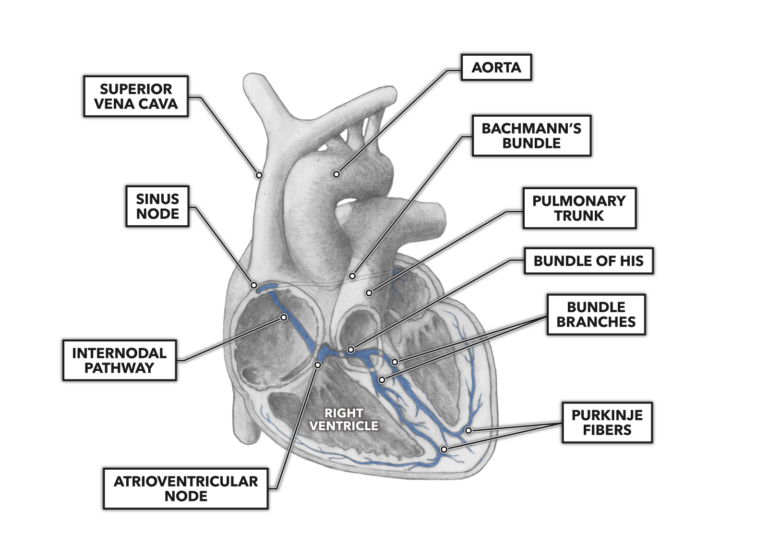

The cardiac electro-conductive pathway is commonly divided into seven components:

- sinoatrial node

- internodal tract

- Bachmann’s bundle

- atrioventricular node

- bundle of His

- right and left bundle branches

- Purkinje fibers

Note that all the anatomical features depicted here are not identifiable by simple visual inspection; a microscopic examination is required.

All cardiomyocytes possess a unique electrical capacity: They are autorhythmic. This means each cell can generate its own electrical stimulus to drive contraction. If the normal electro-conductive pathway fails, a cardiomyocyte or group of cardiomyocytes can take over and keep the heart beating — albeit with greatly reduced efficiency (and yes, this means that in all those sci-fi and horror movies you’ve seen, the heart still beating after it has been precipitously and involuntarily removed from the thoracic cavity of an unfortunate character does have a basis in reality).

In a normal and healthy heart, the stimulus to begin the cardiac cycle of contraction begins at the sinoatrial node. Located in the superior right atrial wall, the sinoatrial node is considered the physiological pacemaker of the heart, setting the tempo of the heart rate. When someone has an artificial pacemaker surgically implanted, it is generally because their anatomical sinoatrial node is failing to produce a proper heart rate or is producing irregular rhythms. The sinoatrial node stimulates both atria to contract. It is located within the right atrium, driving contraction laterally to the left atrium via Bachmann’s bundle.

Electrical impulses also traverse, superior to inferior, the length of the right atrium by way of the internodal tract. The internodal tract conducts the impulses generated at the sinoatrial node to the atrioventricular node.

The atrioventricular node lies fairly superficially in the inner surface of the inferior right atrial wall, a short distance from the ventricular septum. The atrioventricular node contains the same type of specialized conductive cells as the sinoatrial node. However, the atrioventricular node has a very distinguishing functional feature not seen in its superior counterpart: a fibrous sheath covering its surface. This sheath is not as conductive as the node itself and delays the conduction of the electrical impulse. It acts as a sort of anatomical timer, allowing atrial contraction to occur before the ventricles receive their starting impulse. Once the impulse clears the sheath and reaches the atrioventricular node, the diameter of the subsequent conductive feature is larger and as a result conducts electrical impulses more rapidly.

The atrioventricular node leads next to the bundle of His, which conducts impulses from the bundle, turns inferiorly, and penetrates the ventricular septum. It then divides into the right and left bundle branches that direct themselves and their later offshoots to the right and left ventricles, respectively.

These offshoot branches are called Purkinje fibers and are the terminus of the conduction system. They branch and divide extensively down the length of the septum then up and around the ventricular walls, enveloping and penetrating the ventricular muscle in a conductive network. This network enables the nearly instantaneous spread of a contractile stimulus, which causes the large ventricular muscle mass to contract as a single unit. With the sequential and separate contraction of the atria and ventricles, blood can then be moved in a controlled and directional manner that is responsive to biological demand.