As soon as you put food or a drink into your mouth, you begin the process of deriving nutrition and energy from it. In respect to the full digestive process, what occurs in the mouth is a small but important fraction.

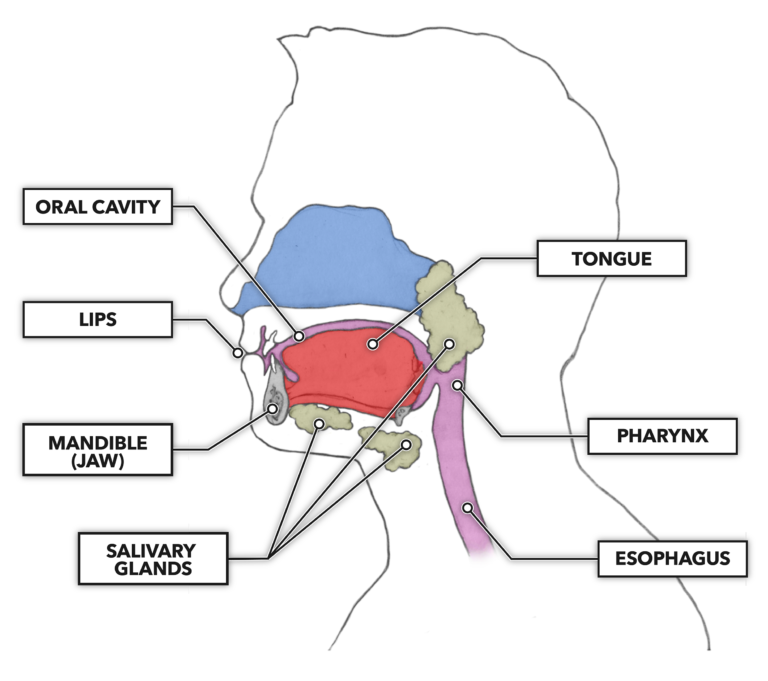

Figure 1: The lips, mouth, and tongue mark the starting point for the passage of food and drink through the gastrointestinal system.

The lips are the gateway to the mouth and are invested with exquisitely controlled muscles that can manipulate food and seal the oral cavity. Externally, the lips are covered with skin. Internally, they are lined with a mucus membrane that contains mucus-secreting glands.

The cheeks form the lateral boundaries of the oral cavity and are contiguous with the lips. Like the lips, they have a layered structure. On the inner surface of each cheek (right and left) and opposite the second upper molars (far back) is the duct leading to the largest salivary gland, the parotid. The other salivary glands are found under the lateral borders of the tongue and on the inner and underside of the jawbone. There are 10 discrete muscles embedded in the cheeks and lips that control their position during eating.

During mastication, or chewing, solid foods are broken down into malleable bits that combine with saliva from the salivary glands to create a deformable mass, or bolus, that can be squeezed along the digestive tract.

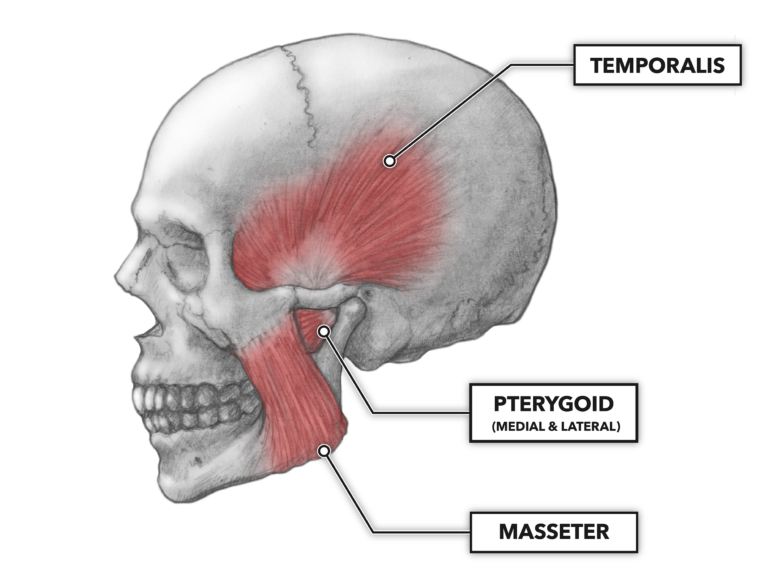

The human jaw can generate 284 newtons or more of bite force (63 pound-force or 29 kilogram-force) and, combined with the tongue’s mobility, can effectively tear and crush foodstuffs into very small and fragmented conglomerates. That force is created via the contractions of four primary muscles: the temporalis, masseter, and two pterygoids (medial and lateral). This destruction of food structure exposes more food surface area and allows the secreted saliva to be thoroughly mixed into the bolus. The moistened food bolus gets shaped into swallowable form via the contracting cheek muscles and the action of the tongue shaping it against the roof of the mouth (the hard palate).

Figure 2: Lateral view of the skull with primary muscles of chewing: masseter, pterygoids, and temporalis. In this image, the distal tendons of the two pterygoids and the temporalis overlap and attach on the inner surface of the jaw.

As we know from experience, we don’t have to bite and chew a great deal to swallow. As long as the bite of food is small enough to slide along the gastrointestinal tube when it is coated in saliva, all is well. Digestion will still be carried out. Only the actions of the enzymes in saliva will be diminished.

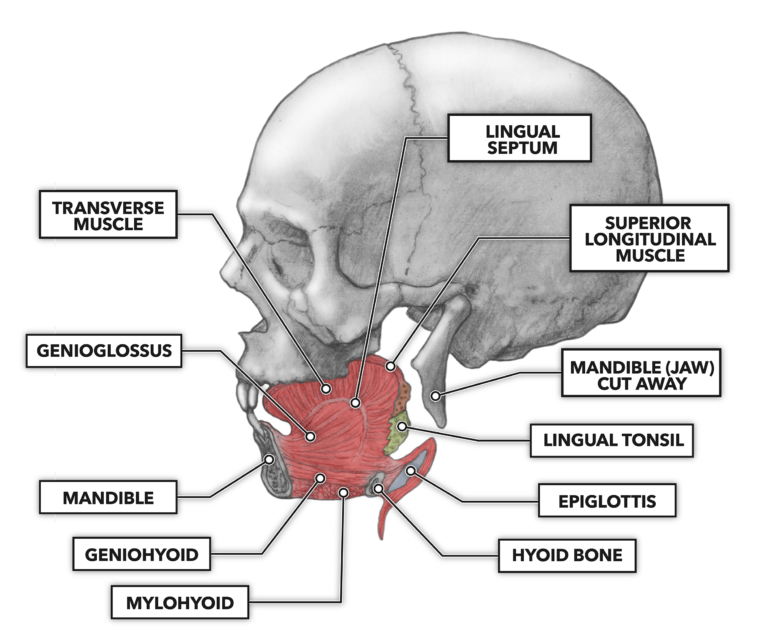

The tongue is an important structure in these early gastrointestinal processes and consists of skeletal muscle attached to the lower jaw (mandible). The tongue is also covered by a mucus membrane that varies in structure and function in its various regions. It is attached to the lower jaw, hyoid bone, skull, soft palate, and the downstream pharynx.

The tongue itself is constructed of many muscles:

- Mylohyoid

- Geniohyoid

- Genioglossus

- Transverse muscle

- Superior longitudinal muscle

- Hypoglossus

- Chondroglossus

- Styloglossus

- Palatoglossus

Figure 3: The tongue is not one muscle but several. The most apparent muscles in the tongue are the mylohyoid, geniohyoid, genioglossus, transverse muscle, and the superior longitudinal muscle.