The passage of a food bolus to the back of the mouth and further down the gastrointestinal tract is accomplished by a clever bit of anatomical design and sequential movement. If the lips form the first gateway to the gastrointestinal tract, a second gateway is formed at the intersection of the oral cavity, the esophagus, and the respiratory tract. The pharynx is the key anatomical structure in coordinating swallowing (scientifically termed “deglutition”). We don’t really think much about swallowing, as it is largely reflexive, but it is a critical process, directing the food bolus into the esophagus by protecting the entry into the trachea.

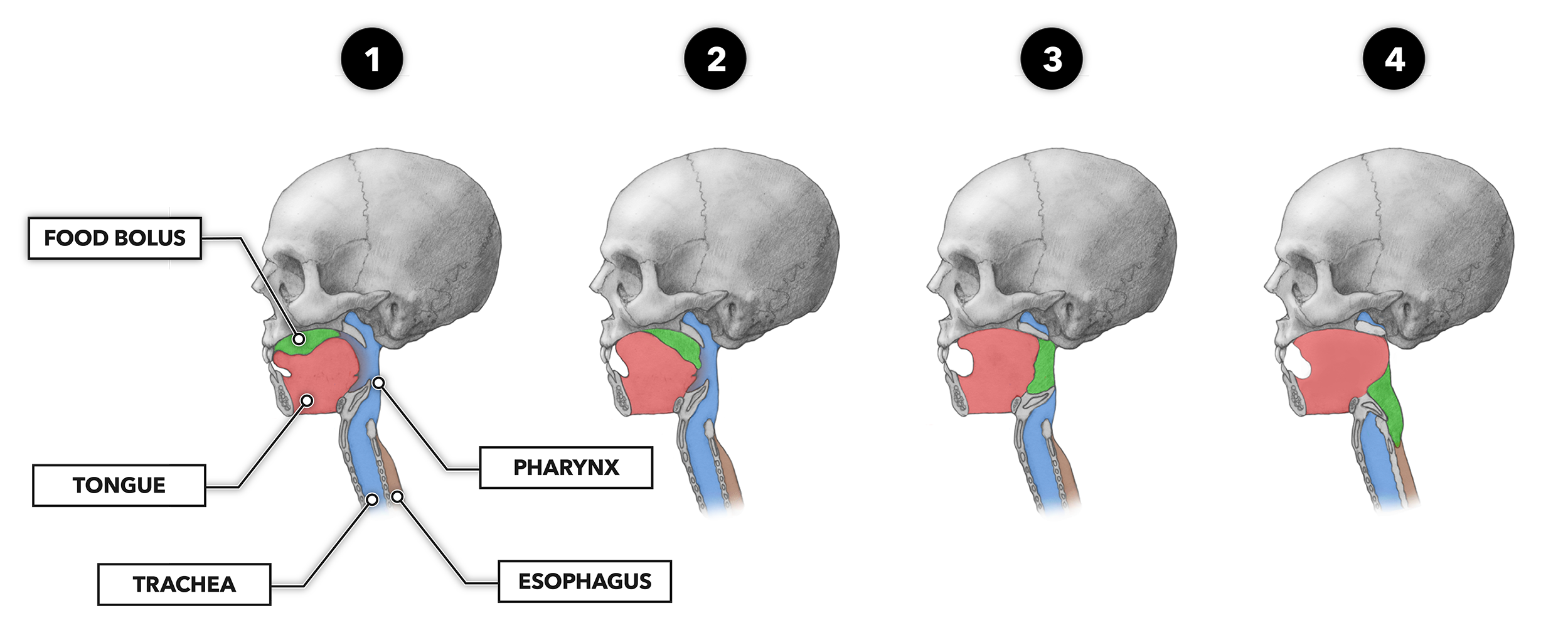

After mastication and salivation create the bolus (1), the tongue elevates against the roof of the mouth to push the bolus to the upper back portion of the oral cavity toward the oropharynx, the superior portion of the pharynx (2). The muscular force is applied first to the anterior roof and then additively applied toward the posterior until the squeezing force has moved the bolus into place to continue the swallowing process. This step is the only one where we can exert voluntary control; we can decide to initiate the process early (bite and swallow), or we can delay it (chew) until we are well satisfied with the condition of the bolus and its readiness to be swallowed.

The entry of a bolus into the oropharynx triggers the firing of a set of mechanoreceptors that send impulses to a higher neural center. After signal processing, a set of impulses is sent to the muscles of the pharynx, larynx, and esophagus. These coordinate contraction of the muscles responsible for propelling food along the gastrointestinal tract toward the upper esophageal sphincter (3).

The nasal cavity is sealed by reflexive contraction of the tensor and levator palatini muscle. This inhibits pressure-driven movements of the bolus upward into the nasal cavity. Additionally, as the tongue contracts and pushes the bolus into the epiglottis, retroversion (tilting or angling backward) steers the bolus toward and into the proximal end of the esophagus (4).

The bolus is prevented from passing into the airway as the vocal folds close via relaxation of the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle and contraction of the oblique, transverse, and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles. All act to close the glottis and draw into contact with the epiglottis. Nearly simultaneously, the pharyngeal structure is elevated and drawn to the anterior by the suprahyoid muscles, and the convergence of the pharynx and esophagus becomes dilated. During this segment of the swallowing process, breathing momentarily pauses. As the bolus crosses the region, there is about a one second — plus or minus about a half a second — of apnea (absence of breath).

Within the pharynx, muscle contraction moves the bolus along the gastrointestinal tube. Peristaltic movement created by constrictor muscles — bands of muscles encircling the tube — squeezes the bolus downstream. This movement occurs quickly and in coordination with the airway blockade. In less than a second, the bolus moves down to a third gateway, the upper esophageal sphincter.

The upper esophageal sphincter is in contraction normally, but when swallowing occurs, the reflexive wave of contractile stimuli impinges on the thyrohyoid muscle. Its reflexive contraction pulls the larynx and hyoid bone up and forward. This acts to stretch open the sphincter while the cricopharyngeus muscle simultaneously relaxes to facilitate dilation. Once relaxation and dilation occur, upstream pressure exerted on the bolus forces it past the esophageal sphincter and into the proximal esophagus.