The stomach is an important component of the gastrointestinal system, and if we think of the GI system as a tube, the stomach has the largest diameter of any point along that tube. With its expanded capacity, this container receives ingested and masticated food and drink from the esophagus. This material is then subjected to further mechanical and chemical degradative processes. New contents of the stomach spend about two to four hours being digested before they pass out of the stomach and into the small intestines.

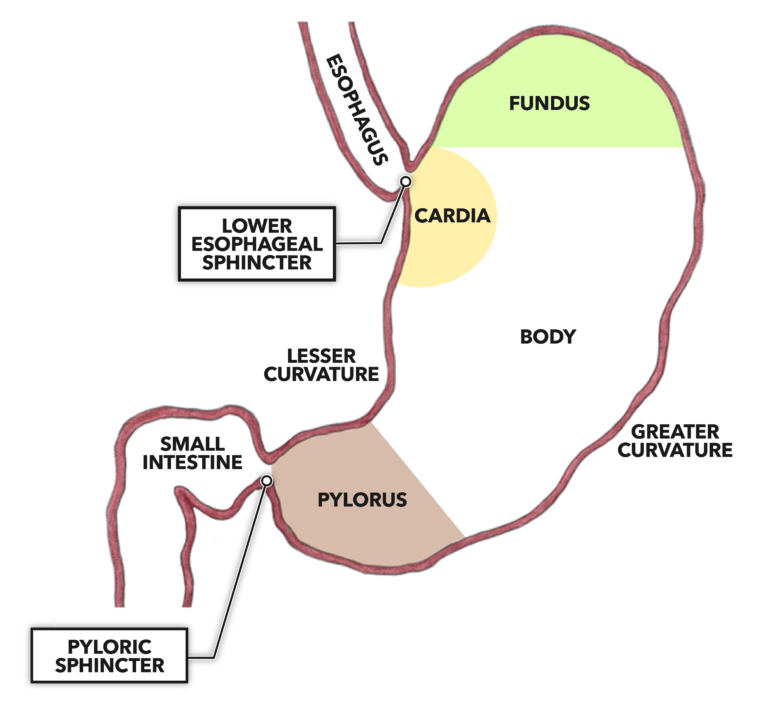

The stomach sits toward the left of the body’s midline and in the upper portion of the abdominal cavity below the diaphragm. It is relatively large, with an internal volume ranging from as low as 50 mL (0.2 cups) when empty up to 3 to 4 L (0.75 to 1 gallon) when completely distended. From the lower esophageal sphincter to its transition to the small intestines is a distance of about 16 cm (6.3 inches) along the lesser curvature and about 22 cm (8.7 inches) along the greater curvature. Within those dimensions there are four main anatomical regions;

Cardia – Sequential to the esophagus. The name indicates its proximity to the heart.

Fundus – The uppermost, dome-shaped portion of the stomach.

Body – The largest diameter portion of the stomach.

Pylorus – The tapered, funnel-shaped portion that leads to the small intestine.

Figure 1: The stomach is a roughly conical expansion of the gastrointestinal tube between the esophagus and small intestine.

The diameter of the stomach will vary according to the volume of food and drink it contains and the activity of the significant amount of smooth muscle present within its walls. As with the esophagus, the stomach comprises four layers:

Mucosa – The innermost layer (bounding the lumen) is composed of epithelial cells, extracellular matrices, mucus glands, and gastric glands. Mucus glands secrete mucus and provide protection from digestion for the cells that line the stomach. That protection is required as the gastric glands secrete fluids containing digesting chemicals, including hydrochloric acid and pepsin, which break down proteins into peptides.

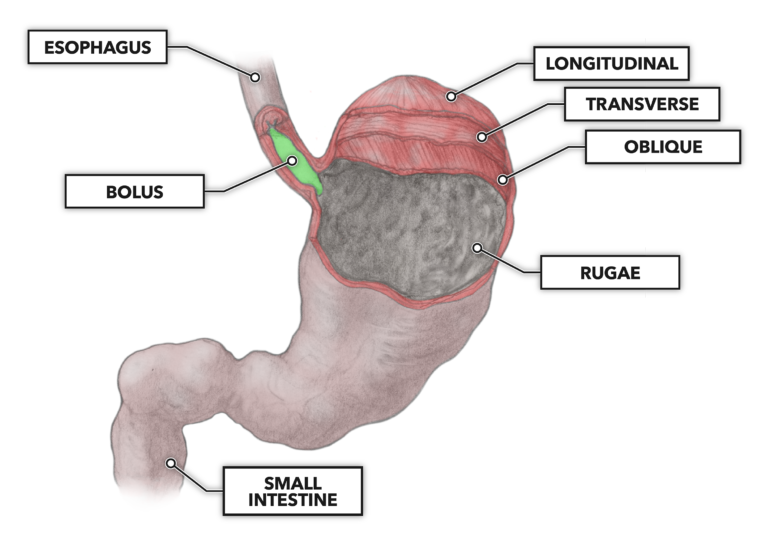

Submucosa – The next-innermost layer is composed largely of connective tissue perforated by blood vessels and contains mucus glands. This layer also is structured to create the labyrinthine, fold-like structures seen lining the stomach, called rugae. These folds flatten to allow stomach distension to accommodate incoming volumes of food and drink.

Muscularis – The third layer is the muscular layer. Within this layer there are three further directional layers of smooth muscle. The innermost layer is oriented along an oblique axis to the body, the middle layer is concentric around the diameter of the stomach, and the outermost layer is longitudinal. Together they contract to mix and move the contents of the stomach downstream toward the small intestine.

Adventitia – The outermost layer of the stomach is composed of connective tissue. It is well supported, as the adventitia is contiguous with other connective tissues, such as the peritoneum, which surround it along its course.

Figure 2: The musculature of the muscularis is layered. From inside to out, the muscularis exhibits oblique orientation of fibers to the long axis, concentric (transverse) orientation of fibers to the long axis, and longitudinal orientation of fibers to the long axis. This orientation facilitates mixing of stomach contents for digestion and downstream peristalsis.