Ligaments connect bone to bone, and as there are 26 bones in the foot, there are numerous ligaments connecting and crisscrossing the foot’s interior. The foot receives quite a bit of support from the simple interlocking of the tarsal bones via their shape and via the intertarsal ligaments. These joints and their ligaments are named for the various tarsals that form the individual joints. For example, they include the talocalcaneonavicular, calcaneocuboid, cuneonavicular, cuboideonavicular, intercuneiform, and cuneocuboid structures. There are other ligaments that are less conventional in naming.

We generally think of muscles as the supportive elements of the skeleton, with bone shape and muscle tone keeping things aligned. But in the foot, ligaments are quite prominent in longitudinal arch support. There are a few ligaments that hold special importance given their role in maintaining the integrity and function of the arch of the foot. These plantar ligaments are primary contributors to arch stability during static posture. It is not until we start moving that the muscles begin contributing to arch maintenance.

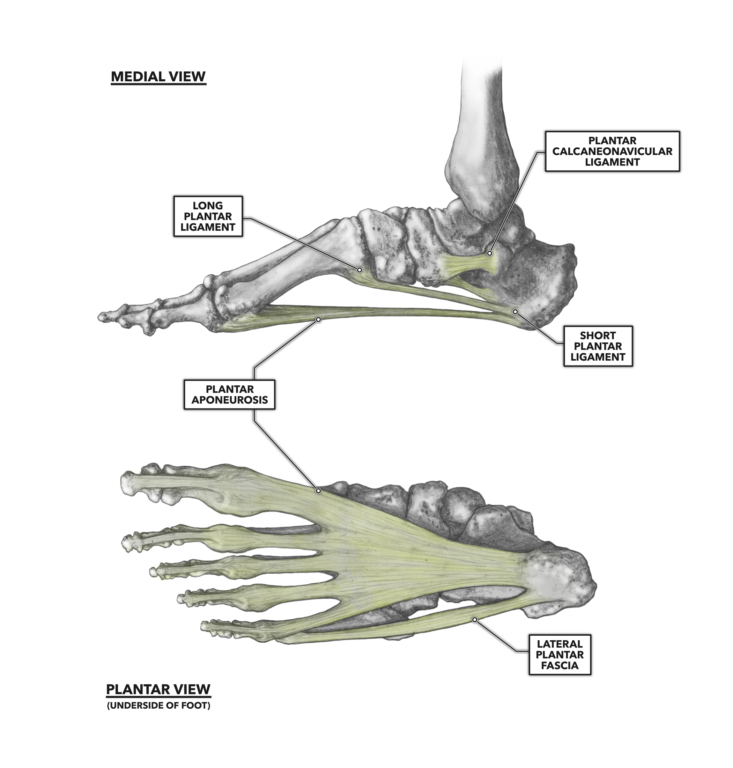

Figure 1: The ligaments of the foot

Long plantar ligament – The long plantar ligament is attached to the midanterior, lateral, and inferior surface of the calcaneus, and to the inferior tuberosity of the cuboid. The ligament then splits and extends to the proximal bases of the metatarsals.

Calcaneonavicular ligament – The calcaneonavicular ligament is medial to the long plantar ligament and attaches to the anterior calcaneus and the navicular. This is a broader but shorter ligament than the long plantar.

Short plantar ligament – This ligament courses between the anterior calcaneus and the inferior cuboid. As such, it is also known as the calcaneocuboid ligament.

Together, these ligaments are frequently called the spring ligament complex, after the resemblance of the foot arch to an automotive leaf spring. You could also visualize the foot’s arch-ligament structure as similar to the arch of a bow with the long plantar ligament as the traditional long string attached near both ends. The other two ligaments can be thought of as additional and shorter strings with one of their ends attached closer to the handgrip. When one of these ligaments fails, the remaining ligaments assume the load. As a result, they are forcefully lengthened and the arch becomes flatter.

The foot has other connective tissue structures that are similar in some ways to ligaments but not classified as such. Note that the non-tendinous and non-ligamentous connective tissue of the foot is effuse and highly intermeshed with the adjacent connective structures with which they share functions. Fascia and aponeuroses are sheets of connective tissue that are widely distributed throughout the foot. Ligaments and tendons of the foot are enshrouded in them at every anatomical level, superficial to deep. The two largest such structures are the plantar aponeurosis and the lateral plantar fascia.

Plantar aponeurosis – The plantar aponeurosis is a relatively thick band of connective tissue that, like the ligaments, supports the arch of the foot. It attaches at the tuberosity of the calcaneus and runs forward to the heads of the metatarsal bones, where it merges with other fascia and tendons as they course forward along the phalanges.

Lateral plantar fascia – This is a very closely integrated companion to the plantar aponeurosis. It attaches at the calcaneus and the lateral base of the fifth metatarsal. It, too, supports the arch of the foot.

Additional Reading

To learn more about human movement and the CrossFit methodology, visit CrossFit Training.