For many years, it was believed there was only one form of diabetes and it mainly affected children. We know the disease has been around for a long time, having been recognized and described by Roman physicians. During the British scientific revolution, it was known as “the pissing evil,” a phrase taken from Thomas Willis’ 17th-century discourse on diabetes. The symptoms included passing lots of sweet-tasting urine, severe weight loss, then coma and, inevitably, death.

For many years, diabetes was known as diabetes mellitus — “diabetes” meaning passing a high volume of urine and “mellitus” meaning “sweet.” This term is rarely used today. It was not until 1936 that it was fully recognized that there were two types of diabetes mellitus. In the first type, there is a lack of insulin production due to destruction of the insulin-producing islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. This mainly affects children, although it does also appear in adults. The cause is unknown. In the second form of diabetes, there is not — at least not at first — a lack of insulin. Rather, the situation is that in certain organs — primarily the liver and skeletal muscle — insulin becomes less effective at driving the storage of glucose. So, eventually, the blood glucose level rises, at which point diabetes is diagnosed.

The two types of diabetes have been named and re-named several times over the years. Examples include:

- Type A and type B diabetes

- Juvenile-onset diabetes and adult-onset diabetes

- Insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent diabetes

- Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes

Type 1 and Type 2 are the terms used exclusively now.

There has also been a separate nomenclature to describe the situation where adults develop the form of diabetes normally seen in children. At one time this was called “latent autoimmune diabetes in adults” (LADA). It is now usually called “maturity-onset diabetes of the young” (MODY) and is increasingly diagnosed.

For many years, the primary concern in the management of diabetes of either type was to control the blood glucose levels. This was because very high glucose levels can cause many different forms of damage: peripheral arterial disease (leading to amputations), blindness, kidney failure, heart failure, and suchlike.

However, in later epidemiological studies, it was further recognized that people with diabetes were also far more likely to suffer from cardiovascular disease (CVD) and die of heart attacks and strokes. In women, the increase in risk can be up to 400% (1).

The CVD issues began to emerge around the same time as the dietary guidelines for the prevention of CVD were published. At this point, the dietary advice for people with diabetes also rapidly changed. For many years, the recommendation had been to eat a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet. As Pamela Dyson explains:

Diabetes mellitus has long been considered a disease of carbohydrate metabolism, and before the discovery of insulin in 1921, low carbohydrate starvation diets were the default treatment. From the 1930s through to the 1960s, many experts continued to advise strict carbohydrate restriction, with the result that most people with diabetes adopted a high fat, low carbohydrate diet. (2)

After 1977, diabetes associations, such as the American Diabetes Association, and dietary guidelines worldwide underwent a 180-degree change and began recommending a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet for anyone with diabetes — a complete reversal of previous advice (3).

To an extent, this shift was inevitable. If fat/saturated fat in the diet causes CVD, and diabetes also greatly increases the risk of diabetes, then it would be doubly important for those with diabetes to avoid fat/saturated fat.

In addition, as fat contains twice as many calories per gram as carbohydrates, it was considered that it may also be possible to reduce caloric intake by consuming a high-carbohydrate diet. This would aid weight loss, and weight loss is recommended for the management of Type 2 (if not Type 1) diabetes. The impact of carbohydrates on blood glucose had been relegated to an issue of secondary importance.

However, if fat in the diet is not a causal factor in CVD, which is increasingly accepted to be the case, then it could be that the advice to consume a high-carbohydrate diet may be doing more harm than good. The central metabolic problem in Type 2 diabetes is an inability of insulin to keep blood glucose down. Therefore, advising people with diabetes to eat carbohydrates — which are all converted to simple sugars in the gut — could well worsen blood glucose control.

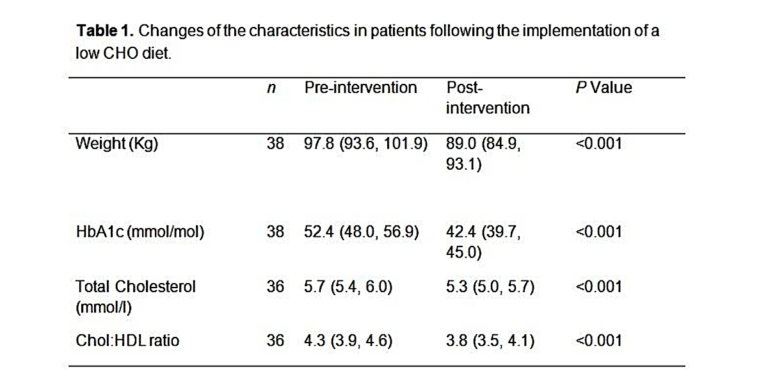

Working on this knowledge, Dr. David Unwin in the U.K. used a low-carbohydrate diet with his patients to see what effect it would have on weight, HbA1c (long-term measure of blood glucose levels), total cholesterol, and the total cholesterol-to-HDL ratio (the lower the ratio the better) (4).

As can be seen, the average weight loss was around 9 kg (20 lb.), the Hba1c reduced by around 20%, cholesterol levels fell, and the total cholesterol-to-HDL ratio improved considerably.

Unwin’s low-carbohydrate program has since been adopted by the Royal College of General Practitioners in the U.K. Many other doctors are now recommending the low-carbohydrate diet to their patents with considerable success, although the mainstream view remains unchanged, which is namely that people with diabetes should eat a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet.

Many individuals have seen considerable improvement from adopting a low-carbohydrate diet. Below is the story of 63-year-old woman:

Kate is a lively 63 year old grandmother who 3 years earlier was diagnosed as pre-diabetic as a routine test showed she had a raised blood sugar level. She was given very little advice and just handed a booklet to read. She followed the advice in the booklet which was to eat plenty of starchy carbohydrate foods, which actually resulted in significant weight gain. Despite this her GP told her to carry on as before. A subsequent test showed that the blood glucose had become even higher and that Kate had developed full blown diabetes. At this point she decided to take control herself. This is the story in her own words:

I decided to take charge of my own disease and destiny, embarking on a read, read and more read programme, it soon made perfect sense that the carbs were the culprit! My newly appointed Diabetes nurse was aghast at my new regime of low carbing, “On your own head be it” were her words! Pretty soon, she had to eat her words as the BG (blood glucose) began to fall without the help of medication and although I wasn’t grossly overweight, my body became toned and healthy at a near perfect 9 stones. The HbA1c result after 8 months was 5.7 and at this juncture, the nurse no longer had an argument, indeed she began to ask me about my regime, taking notes whilst I sang the praises of low carbing. (5)

Perhaps the clearest description of the clinical benefits of a low-carbohydrate diet were outlined by Dr. Eric Westman in the paper “Has carbohydrate-restriction been forgotten as a treatment for diabetes mellitus? A perspective on the ACCORD study design”:

At the end of our clinic day, we go home thinking, “The clinical improvements are so large and obvious, why don’t other doctors understand?” Carbohydrate restriction is easily grasped by patients: Because carbohydrates in the diet raise the blood glucose, and as diabetes is defined by high blood glucose, it makes sense to lower the carbohydrate in the diet. By reducing the carbohydrate in the diet, we have been able to taper patients off as much as 150 units of insulin per day in 8 d, with marked improvement in glycemic control—even normalization of glycemic parameters. (6)

Additional Reading

- The Diet-Heart Hypothesis, Part 1

- The Diet-Heart Hypothesis, Part 2

- The Diet-Heart Hypothesis, Part 3

- The Diet-Heart Hypothesis, Part 4

Malcolm Kendrick is a family practitioner working near Manchester in England. He has a special interest in cardiovascular disease, what causes it, and what may prevent it. He has written three books: The Great Cholesterol Con, Doctoring Data, and A Statin Nation. He has authored several papers in this area and lectures on the subject around the world. He also has a blog, drmalcolmkendrick.org, which stimulates lively debate on a number of different areas of medicine, mainly heart disease.

Malcolm Kendrick is a family practitioner working near Manchester in England. He has a special interest in cardiovascular disease, what causes it, and what may prevent it. He has written three books: The Great Cholesterol Con, Doctoring Data, and A Statin Nation. He has authored several papers in this area and lectures on the subject around the world. He also has a blog, drmalcolmkendrick.org, which stimulates lively debate on a number of different areas of medicine, mainly heart disease.

He is a member of THINCS (The International Network of Cholesterol Sceptics), which is a network of doctors and scientists who believe that cholesterol is not the main underlying cause of heart disease. He remains a proud Scotsman, whisky drinker, and failed fitness fanatic who loves a good scientific debate — in the bar.

He is a member of THINCS (The International Network of Cholesterol Sceptics), which is a network of doctors and scientists who believe that cholesterol is not the main underlying cause of heart disease. He remains a proud Scotsman, whisky drinker, and failed fitness fanatic who loves a good scientific debate — in the bar.

References

- Norhammar A, Schenck-Gustafsson K. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in women. Diabetologia. 56.1(2013):1-9.

- Dyson P. Low Carbohydrate Diets and Type 2 Diabetes: What is the Latest Evidence? Diabetes Ther. 6.4(2015): 411–424.

- American Diabetes Association. Nutrition Principles and Recommendations in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 27.1(2004): s36-s36.

- Unwin D. Working on weight loss with type II diabetic patients. Available here.

- Wheelock V. Coping with diabetes. VernerWheelock.com. 9 April 2014. Accessed Aug. 28, 2019. Available here.

- Westman E, and Vernon M. Has carbohydrate-restriction been forgotten as a treatment for diabetes mellitus? A perspective on the ACCORD study design. Nutrition & Metabolism. 5.10 (2008).

Comments on The Diet-Heart Hypothesis, Part 5

It shouldn't be that patients have to machete through the jungle of dietary advice on their own. We desperately need to come to a data-supported consensus that the medical establishent promotes. People are really confused about what they should eat.

Katina,

I sympathize with your comment, but anyone waiting on an accurate "data-supported consensus" is probably going to be waiting forever. The consensus is wrong and has always been wrong, and there are no signs of this changing.

The political obstacles are even greater than the scientific obstacles. The interests that control public health and dietary policy in this country would have to lose control before the consensus could even approach the truth about food. And regulatory capture is just one reason that "consensus" is not a reliable indicator of accuracy, or properly a constituent element of science.

In lieu of a miracle of consensus, we can only take care of the micro: ourselves, our families, our boxes, and our communities generally. This is why it is a grave error to support the "Exercise is Medicine" and "Food is Medicine" campaigns. They are totalitarianism wrapped in the guise of public health. Institutionalized healthcare will not get exercise or diet right, but they certainly will curtail our freedoms. An effort like CrossFit can only succeed precisely because it remains outside the control of healthcare. It would not last a day inside it.

The Diet-Heart Hypothesis, Part 5: Impact on Type 2 Diabetes

2