Rhabdmyolisis (rhabdo) is a condition that occurs when muscle cells spill their contents into the circulation, leading to muscle cell necrosis and a variety of other detrimental effects. Rhabdo is most commonly associated with intense exercise but has also been associated with statin use. One statin, cerivastatin (marketed as Baycol or Lipobay), was withdrawn from the market in 2001 after being associated with approximately 100 rhabdo-related deaths (1). Clinical trials of other statins have not shown high rates of adverse effects, but given that as of 2010, more than 15% of U.S. adults are taking some form of lipid-lowering medication (most commonly statins), even low rates of adverse effects may have clinical significance (2).

The authors of this 2014 paper surveyed existing data from individual published case reports linking statin use to rhabdomyolysis. Ninety-four papers were found covering a total of 112 cases. Half of these cases were in elderly adults (age 66+), and the majority were in men. Previous research has shown approximately 8% of statin-induced rhabdo cases are fatal (3). The majority of these cases involved the use of simvastatin (Zocor), but all currently prescribed statins have been linked to at least one case.

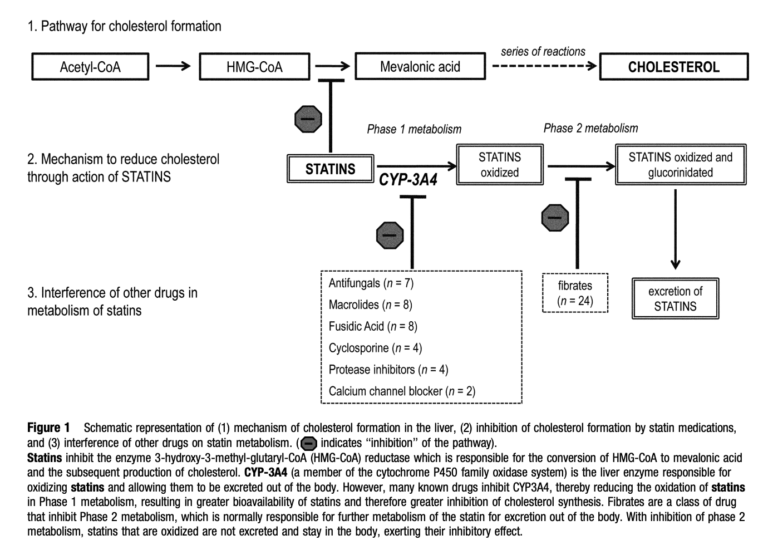

The authors noted the vast majority of cases of statin-induced rhabdo (98% for cases involving simvastatin) were seen in patients concomitantly taking other medications — frequently fibrates (~50% of cases). As shown in the figure below, which outlines the metabolism of statins and their impact on cholesterol production, the majority of these drugs inhibit the oxidation and breakdown of statins. This increases the potency of statins as lipid-lowering medications but may also increase the frequency and severity of side effects.

The authors conclude older male patients, particularly those who have preexisting health conditions and are taking statins alongside other medications, are at greater risk of developing statin-induced rhabdomyolysis, and therefore, signs of rhabdo (such as plasma creatine kinase or urine myoglobin levels) need to be closely monitored.

Additional research can help explain how statins may contribute to the development or progression of rhabdomyolysis, how other drugs may contribute to this progression, and whether these effects can be isolated from the impact of statins on cholesterol levels. As described previously on CrossFit.com in “The Great Statin Scam” and “A Review of Statin Therapy,” any detrimental effects statins may have on muscle weakness and/or muscle function are worth observing closely given the clinical significance of mobility in the elderly populations frequently prescribed statin drugs.