The CrossFit program aims to develop a fitness that is broad, general, and inclusive. To truly pursue and attain this degree of fitness, athletes of all developmental levels should continually strive to learn and master new and more challenging skills.

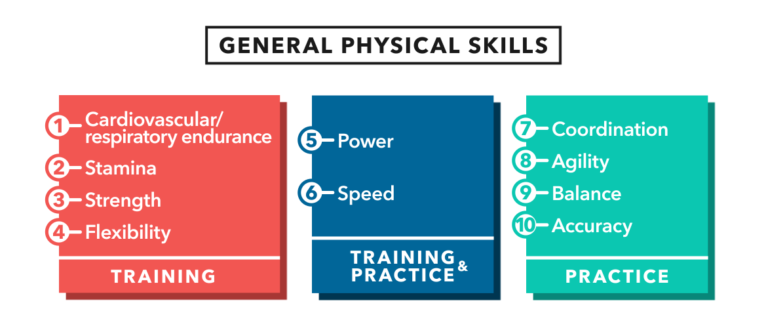

The 10 general physical skills (or capacities), which provide one of CrossFit’s definitional models of fitness, suggest there is much to be gained from persistent and dedicated skill development.

The first four of these capacities are organic adaptations. Improvements in these come through training. Training here refers to any activity that improves performance through a measurable organic change (measurable changes in biological tissue) in the body. Conversely, the final four capacities on the list are largely neurological adaptations that come about through continued practice. Practice here refers to any activity that improves performance through changes in the nervous system, a result of neuromuscular patterning.

We often continue to push ourselves and our clients in training — always seeking heavier loads and quicker times. However, it is less common, especially among more developed or advanced CrossFit athletes, to also continue to practice and push the limits of skill development and neurological adaptations.

Eschewing the more difficult work of pushing existing skills beyond their current threshold in favor of simply refining the core list of common movements to the point of specific efficiency blunts continued development. Neurological capacities will not be broadly developed if the athlete continues to perform only in ways that are already familiar. Challenging an existing level of skill with a new variation of a well-practiced movement or unique combination of movements is absolutely necessary in order to reap the full benefit of CrossFit’s methodology. And, importantly, the acquisition of a new skill is as objective and measurable as lifting a heavier load or achieving a faster time; i.e., you could not previously perform the task and now you can.

The challenge with learning a difficult new skill or variation of an existing skill is that the process necessarily includes a period of time when the athlete will struggle. In order to develop new skills, one must voluntarily place oneself squarely back in the beginner phase. This is often difficult for experienced athletes who have developed a self-perception of competency. However, it is important to properly consider the beginner phase of development, because in this phase, the largest adaptations are made. This is where the distance between inability and competence is the greatest. For example, the beginner weightlifter makes gains at a pace that any competitive lifter would die for later in their career. Regularly tapping into this vital beginner stage is a valuable tool for anyone pursuing broad fitness.

Speaking more specifically, let’s turn our attention toward handstand push-ups and presses to handstand. These movements offer a great study in the nature of skill development. While there are training adaptations that come with handstand practice, such as increased strength and flexibility, the greater demand relates to neuromuscular patterning; i.e., coordination and balance. This only becomes more true as an athlete gains capacity and advances.

CrossFit trainers are skilled in the art of making many difficult movements accessible for the beginner. A good trainer will guide new athletes through a progression, celebrating the small victories along the way. For example, the trainer may start an athlete with a full range of motion push-up, then progress to a dip, then pike push-ups on a box, then finally move to the wall. This process may take years.