The musculature of the shoulder joints is structured and oriented in a manner to provide mobility in every direction around the ball-and-socket joint. It also provides stability, given the relative lack of bony support in the joint.

Muscles of the shoulder can be divided into two strata: the palpable superficial muscles and the non-palpable deep muscles. They are also categorized directionally: anterior, posterior, and lateral.

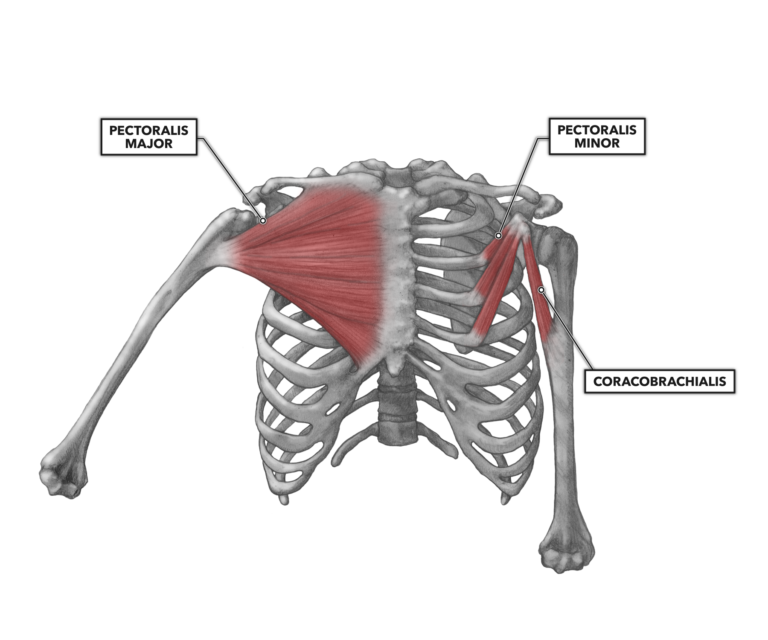

Anterior muscles include the pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, coracobrachialis, and the biceps brachii (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The anterior muscles of the shoulder, including the pectoralis major, the underlying pectoralis minor, and the coracobrachialis, largely underlying the biceps brachii.

Pectoralis major – The pectoralis major, a large and important muscle of the shoulder joint, is likely one of the two most recognized muscles in the body (the biceps brachii being the other). The pectoralis major is a segmented muscle with the segments sharing a common distal attachment to the lip of the bicipital groove of the humerus. The clavicular portion (pars clavicularis) attaches proximally to the inferior and medial half of the clavicle. This clavicular segment is superior and represents a smaller massed segment. The sternal segment (pars sternalis) represents the bulk of the muscle, attaching proximally along the lateral border of the sternum. Both segments also have minor tendinous connections to the ribs near their major proximal attachments.

The primary action driven by the pectoralis major is humeral adduction — i.e., movement of the arm toward center. The muscle is also important in humeral flexion and internal rotation of the humerus. In a relaxed posture, the muscle is important in keeping the head of the humerus in its seat in the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

Pectoralis minor – The pectoralis minor attaches proximally to the upper and outer aspect of the third, fourth, and fifth ribs. It lies underneath the pectoralis major and runs to the superior and medial side of the coracoid process of the scapula, its distal attachment.

The pectoralis minor is a small and not especially strong muscle. When contracting, by virtue of its connection to the coracoid process, the muscle tilts the scapula forward to a small degree. This results in the depression of the point of the shoulder and brings the scapula close to the posterior thoracic ribs.

Coracobrachialis – The coracobrachialis is another small, low-force-producing muscle that attaches proximally at the anterior point of the coracoid process (lateral to the pectoralis minor) and distally to the medial surface of the humerus on the opposite side of the bone from the deltoid tuberosity. The coracobrachialis also aids in the flexion and adduction of the humerus.

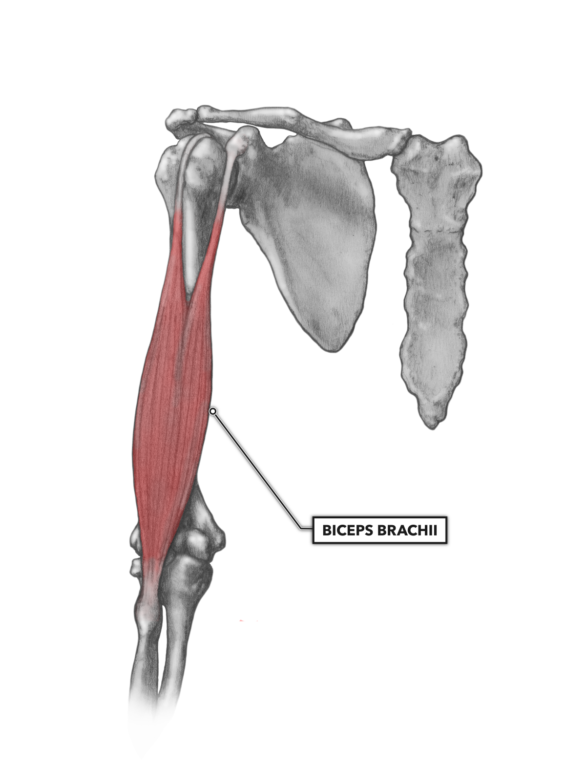

Biceps brachii – Many people are surprised to learn the most recognizable “arm” muscles, those that flex the elbow, are also considered part of the shoulder musculature. The biceps brachii act distally to flex the elbow, but they also act proximally relative to their attachments to the scapula. The short head of the biceps brachii attaches proximally to the anterior point of the coracoid process and long head to the supraglenoid tubercle just above the glenoid fossa of the scapula. Distally, there is a singular attachment to the radial tuberosity (on the radius bone of the forearm). Thus, the muscle crosses and acts at two joints (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The biceps brachii attaches to two points on the scapula.

This means if the hand is held static, the biceps can pull the scapula up and/or tilt it to the anterior. This attachment arrangement can also produce glenohumeral flexion as a proximal function (the hand is the stable end of the system and the body is mobile). This especially occurs in chin-ups, pull-ups, or during climbing. In a standing or seated position with some form of resistance in the hands or on the arms, the scapula will most likely be held static and the biceps brachii will carry out its distal function: the flexion of the elbow.

To learn more about human movement and the CrossFit methodology, visit CrossFit Training.