This paper summarizes the findings from the 2017 CrossFit Foundation Academic Conference, “Diet and Cardiometabolic Health – Beyond Calories.” The conference was convened to consider a specific question from multiple angles: Do specific dietary components have an impact on metabolism and/or disease risk that is not fully explained by their caloric value?

Specific questions included:

- Do certain dietary components increase cardiometabolic risk? (Here, fats and sugars were investigated specifically.)

- Do certain dietary patterns or components promote fat gain or regain? (Here, the relative amounts of carbohydrate and fat in the diet, as well as sugar and artificial sweeteners specifically, were investigated.)

During their talks, conference speakers highlighted an overarching issue: The existing evidence in nutrition science fails to provide clear, consistent answers to these questions. This is generally due to various logistical considerations that severely limit the value of nutrition research. For example, the cost of a trial that would rigorously test the impact of specific dietary factors on heart disease is so large as to render it infeasible; additionally, much of the research investigating diet’s impact on weight loss has been confounded by poor compliance and adherence.

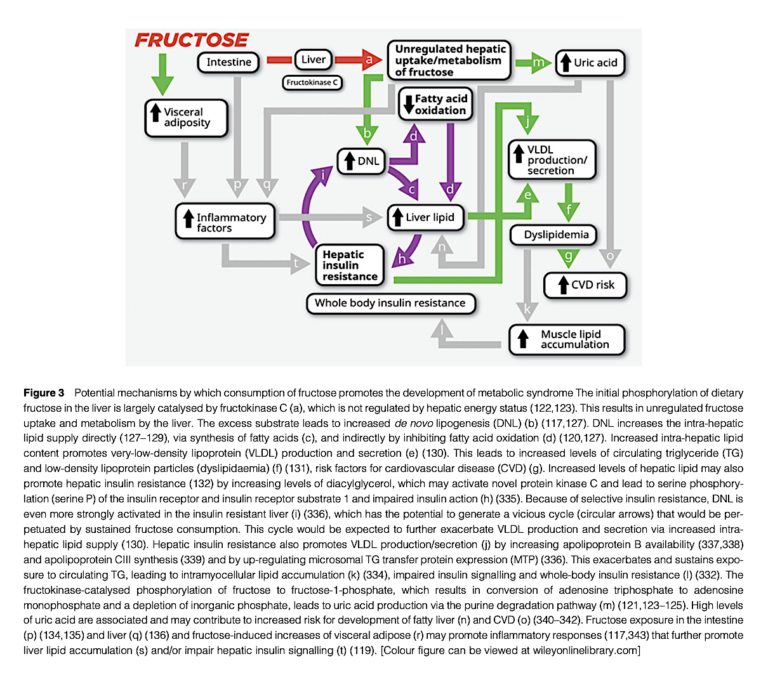

The single strongest conclusion that emerged from the conference drew from the evidence linking consumption of added sugars to cardiometabolic risk. Compared to other carbohydrates (e.g., starch), added sugars lead to greater increases in a variety of cardiometabolic risk factors. This increased risk is largely tied to the effect of fructose on the liver, where it increases fat production (de novo lipogenesis), decreases fat consumption (oxidation), increases liver fat content, and increases production and secretion of very low-density lipoproteins. The first three of these effects negatively impact liver health, increasing cardiovascular risk through multiple mechanisms, while the final directly contributes to a less favorable lipid profile. These mechanisms are summarized in Figure 3 below.

The conference highlighted the weak and often equivocal nature of the majority of nutritional evidence, which results directly from the low quality of the research this evidence is based on. Future evidence ought to be evaluated with respect to the relative weakness of existing hypotheses.

Comments on Pathways and mechanisms linking dietary components to cardiometabolic disease: thinking beyond calories

Interestingly enough, the Citgo executives detained in Venezuela were fed only "rice and pasta" and became pre-diabetic and hypertensive, despite losing tens of pounds. A calorie is NOT a calorie!

Sesin, Carmen. “No End in Sight, Families of Citgo Executives Jailed in Venezuela Push for Answers.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 19 June 2019, www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/no-relief-sight-families-citgo-executives-jailed-venezuela-seek-answers-n1018071.

Pathways and mechanisms linking dietary components to cardiometabolic disease: thinking beyond calories

1