The nutrition recommendation presented in Fitness in 100 Words has withstood the test of time:

Eat meat and vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, little starch, and no sugar. Keep intake to levels that will support exercise but not body fat.

Who has said more about nutrition in fewer words than this? No one. But it does leave open the question of timing. Is the current state of scientific knowledge and clinical practice advanced enough to offer similarly clear and unambiguous advice? Here goes:

Eat half the day, mostly at regular meal times, and not too late.

Beyond this, there is room for variation and fine-tuning between individuals. The 13 words above should be seen as a starting point.

What we eat (quality), how much we eat (quantity), and when we eat (chrononutrition) all affect our health and performance. However, compared to the other two factors, chrononutrition is arguably the weakest of the three. Many studies on intermittent fasting use high-carb diets with an abundance of processed foods. Despite this, study participants often still manage to eke out improvements in weight and other biomarkers. Clever timing schemes are not a silver bullet, though, and should be understood as a means to squeeze that last 5-10% of optimization out of a good diet and exercise program.

In previous installments in this series, we discussed the key variables of meal timing: meal frequency, the fasting window, and eating at specific times of the day. The scientific literature on chrononutrition is a mess, often showing small or inconsistent effects. The best diet for an individual might come down to decidedly non-scientific factors like enjoying family dinners or Sunday brunches with friends. Figuring out the best diet may require some personal experimentation within the parameters of what is known to be healthy or unhealthy.

The Wrong Answer Is Clear

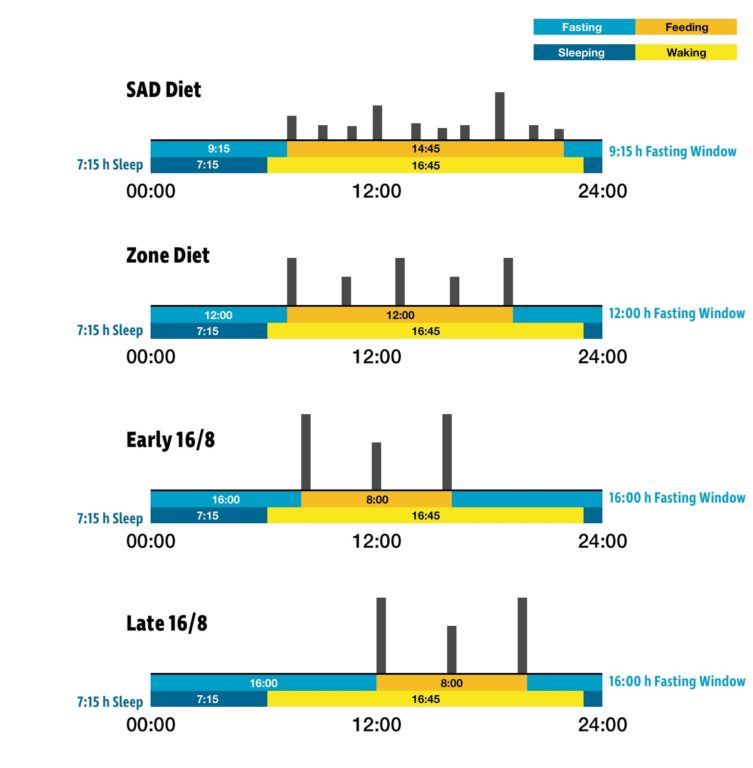

Failure often leaves a trail of breadcrumbs (maybe cookie crumbs in this case). The clearest embodiment of a deranged eating pattern is the average man on the street. A study utilizing a smartphone app revealed the average person’s meals span 14 hours and 45 minutes a day and occur across seven or more occasions. This type of all-day grazing pattern is how ranchers fatten up livestock. It seems to work just as well on humans.

Keep in mind that the numbers above were the average in the study group. A common logical fallacy is to assume that what is average is normal. Under no circumstances should an all-day food fest be considered normal. What has driven us to this food-driven lifestyle?

Food companies are in the business of creating profit, not health. Their snack foods are not made to satisfy our hunger. Snack foods are designed to keep us coming back for more. The contents are so cheap they barely factor into the cost of the product. Dirt-cheap ingredients like wheat, corn, soybean oil, and sugar are made even more economical through government subsidies. Marketing, distribution, packaging, and a whopping 40% profit margin are where your money goes.

Highly refined foods are pre-digested by chemical and mechanical processes before they reach your mouth. Even so-called “whole grains” break down so fast they are essentially sugar. On top of this, grains contain proteins called gliadins that break down into opioid peptides. Dr. William Davis explains:

We … know that foods contain proteins that, upon partial digestion, yield components that exert opioid behavior and even resemble the structure of morphine. The gliadin protein of wheat and related grains yields so-called gliadorphins, while the casein protein of mammary gland products yields casomorphin. No, nobody is going to the emergency room with acute bagel or muffin overdose. The health effects of wheat and related grains are less acute, more chronic, but no less important.

What luck for the food companies that the cheapest ingredients are also addictive. Considering these processed foods make up 57.9% of energy intake in the United States, it’s no wonder our eating habits have been so shaped by these foods.

Here’s the standard American diet (SAD) in 36 words:

Wheat, corn and seed oil, plenty of starch and sugar, some meat, little fruit, and no vegetables, all highly processed. Eat most of the day, whenever you feel like it, for as long as you’re awake.

Improving upon this eating pattern should be easy, but for most people it’s not. Highly addictive foods create a battle between your hunger hormones and your willpower. Biology beats psychology (almost) every time. Refined carbs offer a quick burst of energy and dopamine (the pleasure/reward hormone) followed by a crash. We barely digest one snack before reaching into the bag for another — and so continues the pattern that leads to all-day eating.

Normalized eating patterns start with choosing the right foods: meat and vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, little starch, and no sugar. Once you have the right foods on the table, the correct amount is usually within striking distance. How you partition good food in the correct amount throughout the day is what we’ll discuss going forward.

Sample Meal Patterns

The Zone diet is explained in CrossFit Journal Issue 21 and the Level 1 Training Guide. In addition to the famous 40-30-30 macronutrient ratio, Dr. Barry Sears also recommends a specific meal pattern. To keep hormones such as insulin and glucagon stable throughout the day, the Zone diet recommends three main meals and two snacks per day. Recently, Sears also recommended limiting the eating window to 12 hours.

Although this could be considered a high-frequency eating pattern compared to the examples to follow, it is actually lower frequency than a typical American diet. The fasting window of 12 hours is also two hours and 45 minutes longer than an average American’s. Although Sears rejects intermittent fasting in favor of continuous caloric restriction, a 12-hour fasting window is not extreme and should not be a struggle for a metabolically healthy person.

The most important thing the Zone diet offers is the block system, which provides an easy way to track macros and portion sizes. If you are consistent in tracking your blocks, you will be able to run experiments to find out what works best for you. If your diet is sloppy and inconsistent, any intentional changes you make could be confounded by unintentional variation.

The 16/8 meal pattern entails fasting for two-thirds of the day and eating all your meals in the eight remaining hours. Many people also like the simplicity of not having to worry about food for much of the day. Many people follow this pattern simply by skipping breakfast. Rather than maintaining stable insulin and blood sugar, the idea here is to drive both down for as much of the day as possible to increase utilization of stored body fat.

As mentioned in part two of this series, studies have shown this time-restricted eating pattern can result in greater fat loss than a standard eating pattern while maintaining lean muscle mass.

Moving toward a longer fasting window often means eating fewer but larger meals. It doesn’t make sense to eat five meals within a short eating window. Time-restricted eaters usually consume two or three meals or two meals and a snack.

Skipping breakfast is not the only option. Skipping dinner is also viable, and at least one study has shown the benefits of this early time-restricted feeding approach when compared to a normal eating window. The study did not compare this pattern to a late eating window, however.

Extending the Fasting Window

In a review published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Rafael de Cabo and Mark Mattson reported a variety of metabolic health improvements via intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating, including:

- Weight and fat loss

- Lower blood pressure

- Improved glycemic control

- Reduced systemic inflammation and oxidative stress

- Improved cellular stress resistance, antioxidant defense, and DNA repair

- Increased autophagy

In the paper, they discuss the benefits of intermittent fasting on cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, obesity and diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. They claim:

Intermittent fasting improves multiple indicators of cardiovascular health in animals and humans, including blood pressure; resting heart rate; levels of high-density and low-density lipoprotein (HDL and LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin; and insulin resistance. In addition, intermittent fasting reduces markers of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress that are associated with atherosclerosis.

Intermittent fasting and time-restricted fasting is no longer the domain of basement biohackers. It has gained the attention of prestigious medical journals, Hollywood actors, and top athletes. For improved metabolic health and increased fat loss, it’s worth experimenting with a longer fasting window. This is one of the least difficult changes to make to your diet, but the first few weeks can be rough. Moodiness and low energy are not uncommon in the first few weeks. Extending the window by an hour every week or two should help smooth out the transition, though.

The Circadian Factor

Shifting your eating window toward the morning or evening is another parameter that can be fine-tuned. In part three, we explored the science of circadian rhythms. This daily fluctuation in metabolic function primes our digestive system in anticipation of food. Off-schedule eating sends food into your body when it is not ready for it, resulting in suboptimal digestion and elevated blood glucose. Simply maintaining a regular eating schedule, including consistency over the weekend days, helps entrain a strong circadian rhythm.

Breakfast is frequently touted as the most important meal of the day, because insulin sensitivity peaks in the morning and subsequently declines as the day goes on. However, research has shown that this is at least partially a trained effect. In one study, skipping breakfast was associated with poor outcomes only in people who habitually eat breakfast. Epidemiological research has reported a lower average BMI in countries that consume their largest meal at lunch (European countries) as opposed to dinner (North American countries). However, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies on eating/skipping breakfast showed a slight bias in favor of skipping the meal, to the tune of .44 kg across the seven included studies. The trials ranged from two to 16 weeks in duration.

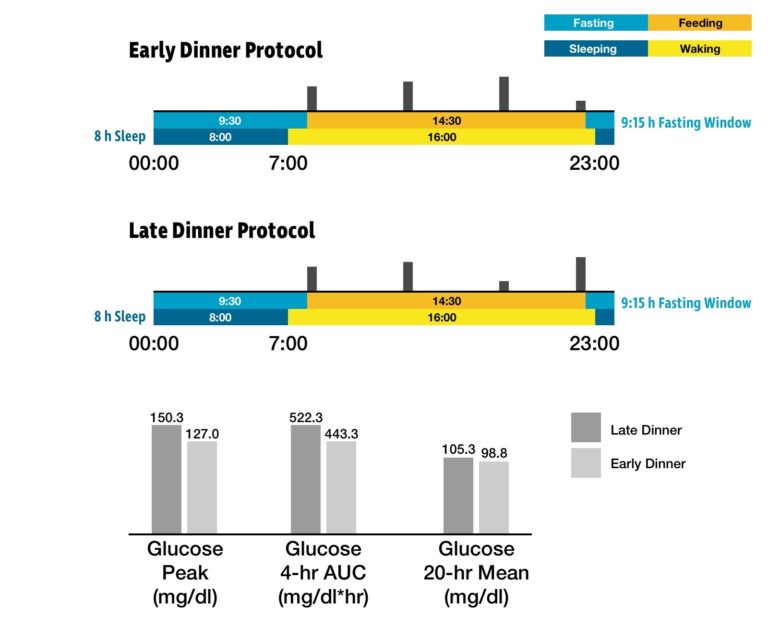

Adapted from Gu et al. (2020)

Another study, published a few weeks ago, tested the effects of either a late snack or a late dinner. In a randomized crossover design, the participants ate a snack at 18:00 and dinner at 22:00 (LD, late dinner) or ate dinner at 18:00 and a snack at 22:00. The researchers tested the effects of both protocols on blood glucose, insulin, and free fatty acid (FFA) metabolism. Higher blood glucose levels and blunted FFA utilization were observed in the late dinner group. Late dinner-induced glucose intolerance was more pronounced in study participants who were habitually early sleepers.

This study suggests it is wise to avoid eating close to your bedtime. Melatonin, the sleep hormone, binds to the insulin-producing cells in your pancreas, reducing their output. This is one possible explanation for poor glycemic control near the onset of sleep. Keep in mind that this study only tested the short-term effects of a single meal on two occasions. Also of note, the 20-hour mean glucose was slightly higher, but FFA levels and insulin were not significantly different between either condition. So, don’t lose sleep worrying if you occasionally eat a meal too late.

One important factor in our community is how meal intake should be timed in relation to our workouts. There is a near-unanimous consensus that post-workout meals are important and should perhaps be the largest meal of the day. In the few hours post-workout, we are most insulin sensitive as our muscles are in a primed state to take in glucose and amino acids. Late eating is likely to be less problematic if you train in the evening.

There is far less agreement on pre-workout nutrition. Fasted training is loved by some and hated by others. It’s a topic worth exploring more in the future.

The Best Eating Pattern According to Science

If you were to assess every possible combination of meal frequencies, fasting windows and times of day, you would have (very roughly) the following options:

- Low (1-2 meals/day), medium (3-5 meals/day), or high (6+ meals/day) frequency

- Short (<12 hours), medium (12-16 hours), or long (>16 hours) fasting window

- Early, middle, or late in the day eating

Do the math and you get 27 different eating patterns. Imagine the size and scope of scientific research required to test all 27 possibilities. And not just in college-aged males but in a variety of populations: old, young, women, men, obese, frail, Type 2 diabetics, different ethnicities, etc. The amount of research required would be enormous. The fact is that there is no scientifically proven best eating pattern, and it’s doubtful a clear, one-size-fits-all answer will emerge any time soon.

The best eating pattern is one that not only makes you feel and perform well but also fits your lifestyle. One study showed modest benefits to eating 17 meals versus three meals per day. Is becoming a full-time eater worth an 8% drop in cholesterol? Other studies have shown benefits to eating only once a day. Is stuffing yourself full, past the point of comfort, something you will stick with long term? A program is only as good as your willingness and ability to stick with it.

Science might not have all the answers yet, but we know the standard American diet is messed up. Eating half the day, mostly at regular meal times, and not too late is surely a step in the right direction. Please post your eating pattern to the comments. I would love to hear of your experiments and experiences.