In previous installments, we looked at meal frequency and the fasting window. These variables dictate how much of the day you spend eating and the time between meals. However, we have yet to talk about meal timing: whether you eat in the morning, midday, evening, or at night (or all four in some unfortunate cases).

Experts have long advised us that “breakfast is the most important meal of the day” and eating late at night leads to weight gain. Epidemiological evidence supported these contentions. Early eaters are on average thinner and healthier than late eaters. Breakfast skippers are on average poorer and less educated. They rarely exercise, but smoke and drink regularly. What gives?

This is called a “healthy user bias.” The healthiest people in a given population tend to follow whatever the health authorities say, even if some of their advice is dubious. Those who dutifully eat breakfast are also more likely to avoid red meat, eat organic, exercise, and drink alkaline water instead of alcohol. Some of it may be hokum, but on average, people actively engaged in improving their health tend to be healthier.

Likewise, night time eating is often demonized as leading to weight gain and other metabolic health issues. This ignores the possibility that poor metabolic health leads to late-night eating. Ravenous hunger and frequent eating go hand in hand. It would be surprising if this effect were only observed during the daytime.

Night and Day

In an article published earlier this year, Dr. Terence Kealey debunked the myth that breakfast is the most important meal of the day. His sensible advice was to eat it if you’re genuinely hungry but skip it if you’re not. Eating breakfast out of “metabolic duty” is counterproductive.

The few published randomized controlled trials related to this topic have not shown evidence to support the primacy of breakfast.

A 2017 meta-analysis questioned whether large dinners led to weight gain:

Four observational studies showed a positive association between large evening intake and BMI, five showed no association and one showed an inverse relationship. The meta-analysis of observational studies showed a non-significant trend between BMI and evening intake (P=0·06). The meta-analysis of intervention trials showed no difference in weight change between small and large dinner groups (-0·89 kg; 95 % CI -2·52, 0·75, P=0·29).

Essentially, the association between late night eating and BMI is weak and goes away as the studies become more controlled. The authors concluded, “Recommendations to reduce evening intake for weight loss cannot be substantiated by clinical evidence.”

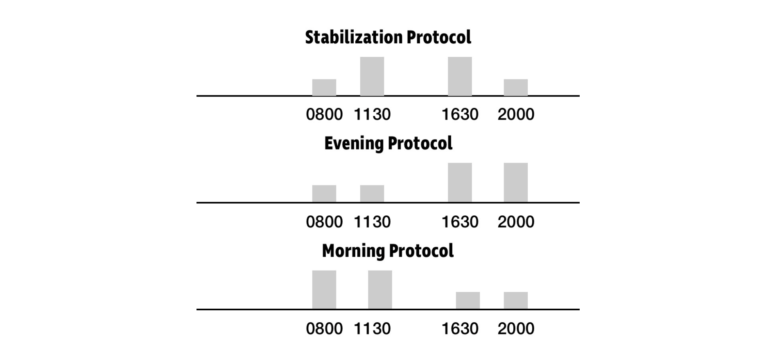

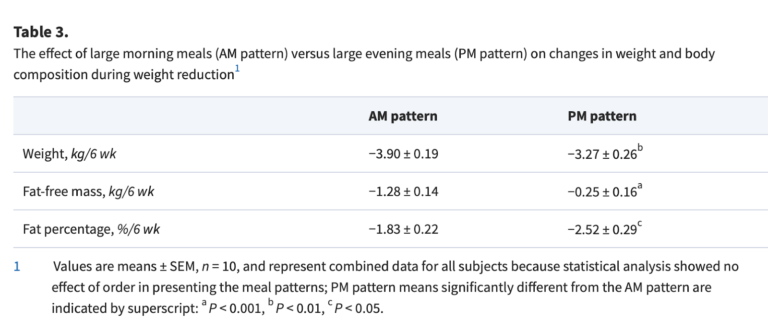

In one study of daytime versus nighttime eating, 10 overweight women spent 15 weeks in a metabolic ward. You read that right, they lived for 105 consecutive days in a metabolic ward. The first three weeks were for weight stabilization and followed by two consecutive 6-week periods of weight loss. During the first period, the women consumed 70% of their caloric intake early in the day or at night. In the second period, they switched from night to day or day to night. The diet macronutrient profile was 60% carbohydrate, 18% protein, and 22% fat. Participants also exercised by walking outdoors daily, cycling or walking on a treadmill five days a week, and performing machine-based resistance training three times a week.

All three timing protocols included two meals of 35% total daily calories and two snacks of 15% total daily calories.

All three timing protocols included two meals of 35% total daily calories and two snacks of 15% total daily calories.

In spite of this high-carbohydrate diet, women experienced greater reductions in body weight, including lean mass during the morning protocol. The evening group lost more fat, with only a minimal reduction in lean mass.

The study authors advise that early eating can be more effective for weight loss, while late eating might be more effective for preserving lean muscle mass. However, the study leaves many questions unanswered. Would a low-carbohydrate diet have been more effective for weight loss? Does the timing of exercise in relation to food intake matter? More calories are consumed post-exercise in the late eating group, which could explain the muscle sparing effect.

Circadian Clocks

Imagine you would like to build a house. You’ve picked a nice spot and hired the contractors. For the process to go smoothly, a series of events has to happen in the correct order. You need to demolish and clear out what is there before the construction crew starts building something new. Imagine the disaster if the concrete was poured before the demolition crew did their job. Your body is similar in that it goes through a daily cycle of sleeping and waking, fasting and eating, destroying and building. This is all scheduled by what is called our circadian rhythm.

A circadian rhythm is observed in tissues throughout the body. At the highest level, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain acts as a master clock. This small bundle of neurons connects to the optic nerve and is light sensitive. To calibrate to a 24-hour day, a variety of factors, such as temperature, activity, and even social cues, feed into our central clock, but light is the strongest factor in the entrainment of our circadian rhythm.

The SCN is especially sensitive to blue wavelength light. Sunlight provides the full spectrum, including the blue wavelength. As the sun sets, blue light is filtered out by the atmosphere, leaving predominantly red and orange light and in reduced intensity.

This daily variation of light color and intensity is something land animals have evolved with over millions of years. Artificial lights have broken this natural light cycle, providing light throughout the day out of sync with the natural color and intensity. Indoor lighting doesn’t provide the intensity or full spectrum of sunlight. And blue light from LEDs and electronic devices hits us at night, which would never happen in nature.

This state of affairs creates the sensation of daytime when our body clocks expect it to be night time. It is a confusing mix of signals.

Our circadian clocks regulate 10-15% of our gene expression, and 40-50% of these genes relate to metabolism. It is no stretch to say that our metabolism and internal clock are intimately connected.

One hypothesis for why late-night eating is harmful is that melatonin, a hormone released at night to make you sleepy, binds to insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. This makes you less insulin-sensitive at night. Likewise, a bad night of sleep can reduce insulin sensitivity by 19–25%, affecting hepatic (liver) and peripheral glucose metabolism.

In addition to the central clock, peripheral clocks exist throughout the body. These are blind to light, so they are instead regulated by hormonal and neural mechanisms under the control of the SCN. These peripheral clocks are also influenced by the timing of food intake. A shifted eating pattern can offset our peripheral clocks relative to the SCN. When food intake is out of sync with the circadian rhythm, researchers call it metabolic jet lag.

Metabolic Jetlag

Observational studies of shift workers suggest irregular circadian rhythms can contribute to a variety of chronic diseases, including breast cancer, stroke, depression, and heart disease. For ethical reasons, well-controlled, long-term studies on human subjects are not feasible. Socioeconomic factors also confound comparisons between shift workers and regular nine-to-five workers, making observational research tricky.

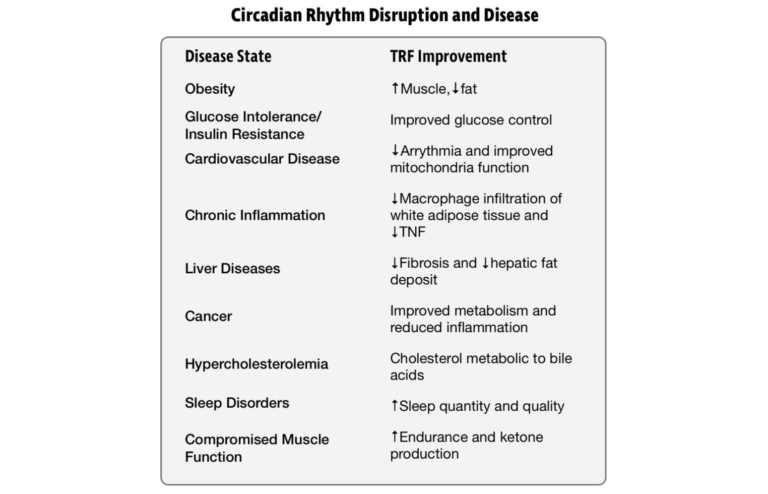

Much of what is known about the health impact of circadian disruption comes from animal studies.

Circadian rhythm disruption is associated with a variety of disease states. Time-restricted feeding has shown beneficial effects in rodents and other model organisms. Adapted from Circadian Physiology of Metabolism.

In the previous installment, we looked at a study by Shubroz Gill and Satchidananda Panda that tracked food intake throughout the day using a smartphone app. It was discovered that the mean feeding window duration was 14 hours and 45 minutes per day. Only 9.7% of the participants had an eating window of less than 12 hours per day. Most people live in a fed state for most of their waking hours.

In the next phase of their study, the researchers selected eight participants with an eating window of greater than 14 hours and directed them to reduce this window to 10-12 hours and also keep the timing consistent day to day.

Over the next 16 weeks, the subjects reduced their eating window by an average of 4 hours and 35 minutes and reduced weekday/weekend variability to less than an hour. Without guidance on caloric intake, subjects reduced calories by an estimated 20%. On average, the subjects lost 3.27 kg, slept better, and felt more energetic. These improvements were maintained at a follow-up appointment a year later.

This hints at the importance of two factors: the fasting window and metabolic jet lag. Based on animal research, an extended fasting window improves circadian rhythms. This could explain the improved sleep quality reported. Likewise, maintaining a consistent sleep and eating schedule from weekday to weekend can potentially mitigate some health issues, such as those experienced by shift workers.

However, we should not live in fear of losing a night’s sleep or mistiming a meal. The effects are small enough that careful study is needed to find them. And the effects are short-term and largely reversible. In animal models, circadian rhythms can reset to a new schedule within four to seven days. Athletes often compete without optimal, regular sleep schedules. And soldiers fight wars under even harsher sleep and eating conditions. The human body is well-adapted to intermittent stressors such as this. Living a perfectly regulated life is neither necessary nor advisable. Too much order is a sign of dysfunction. We should only be concerned by disorder when the stressor becomes chronic.

The Most Important Meal

Are unhealthy eating patterns a cause or consequence of metabolic derangement? It’s likely a two-way street. Bad food leads to erratic eating patterns. And poorly timed meals are not typically what’s healthiest but what is most convenient. If your food quality and quantity are both dialed in, tinkering with the timing of meals is a sensible next step. A healthy eating pattern might even fall into place automatically just by getting the food right.

Let’s put an end to eating out of metabolic duty. Shifting calories toward later in the day is not the scourge it was once thought to be. The most important meal of the day is the healthy one eaten out of genuine hunger.

Additional Reading

Comments on Meal Timing: Chrononutrition

Hi Tyler,

You may find this study on circadian roles interesting. Nice graphs. https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article/18/5/716/2530790

Seems like a fact, glucose creeps higher in the evening postprandially. In healthy individuals, t2d changes that (and changes the morning response, too). Then again, this obsession to glucose metabolism shunts the more interesting FFA ,VLDL aka triglycerides and hormonal changes.

So, if someone likes oral glucose test (75g ) in the evening, the results are 30-50mg higher peak AND softer insulin curve thus longer hyperglycemia. Maybe the ancient homo sapiens, who typically didn't have 75g of sugar/glucose available thru fruits, was anyways in the "storing mode" in the evening. The whole eating pattern is about storing for later use. Similarly, eating is a potential attack, a hazard, which the defence system has to get prepared to. And hormonal response. Don't snack !

Dr. Kealey and due to him, even I dislike Jakubowizc group, who always get remarkable results for dinner-skippers. They think a greater insulin reaction is good, even for t2d, everybody knows t2d's suffer from lack of insulin...

Maybe we can agree upon, that this is rather complicated. If healthy and t2d have different responses, then people with metabolic syndrome should hover in between.

JR

JR,

That's a great paper. It really goes to show that there are many factors that go into glucose regulation. It becomes even trickier to generalize recommendations when you factor in age, obesity, metabolic syndrome and T2D. The graphs are compelling. In healthy people, it does seem like you have a larger AUC for postprandial blood glucose in the evening. This would seem to suggest that eating carbs at night is a bad idea.

However, in this study of Israeli police officers, two groups ate similar calorie-restricted diets, but one of them ate most of their carbs at dinner. So, they were carbohydrate fasting during the day, whereas the other group had their carbs evenly spread throughout the day. The carb-fasters lost more weight, more fat and various hormone levels improved as well (improved insulin sensitivity and raised adiponectin). Markers of inflammation (CRP, IL-6, TNF) were also improved in the carb-fasting group. It would be interesting if there had been a third group eating most of their carbs at breakfast. Then we'd know if the improvements were driven by carb-fasting or circadian factors.

Another thing I find interesting is that melatonin can bind to receptors in the pancreatic islet. If you eat a meal late at night while melatonin levels are high, you might not produce enough insulin to keep blood sugar down. So, it's probably okay to eat in the evening, just not too late.

Meal Timing: Chrononutrition

2