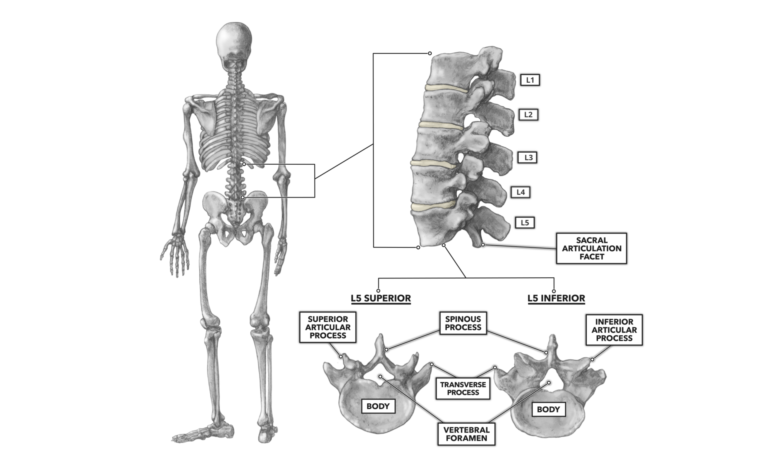

The lumbar vertebrae are the five largest vertebrae. The first lumbar vertebra (L1) is immediately inferior to T12 and the posterior portion of the 12th pair of ribs. The fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) is immediately superior to the sacrum at the center of the posterior pelvis (Figure 1).

These five vertebrae exhibit the same basic structure as the other vertebrae in the vertebral column, differing from the cervical (C1-7) and thoracic (T1-12) vertebrae primarily in terms of size. In general, as we go down the vertebral column from cervical to lumbar, the individual vertebrae bodies get thicker and larger. This makes sense functionally because the magnitude of persistent postural load increases as we proceed down the body from head to toe.

One notable feature of L5 is that its inferior articular facets do not articulate with a sequential and inferior vertebra; they join to the sacrum. We thus call these facets on L5 the sacral articulation facets (Figure 1).

Also of interest are the mobility of the individual lumbar vertebrae and their mobility as a unit. Individually, each vertebra can flex and extend with about a 15-degree range of motion. This is significantly larger than that of the thoracic vertebrae, which can only operate through approximately 2.5 degrees due to the anatomical constraints of the attached costals.

Through flexion and extension, the lumbar vertebrae facilitate about an 85-degree range of motion—60 degrees of flexion and about 25 degrees of extension. The total range of motion of lateral flexion (left + right) is about 50 degrees at the lumbar. While this is quite mobile, the lumbar vertebrae are less so than the cervical vertebrae, which are capable of about 110 degrees of range of motion in flexion and extension, and about 90 degrees in lateral flexion (left + right).

Note: There is a large amount of variation in range of motion and references of measure between individuals, so the above data are estimates for illustration, not absolutes.

Comments on The Lumbar Vertebrae

Hmm interesting

T1-T5??

The Lumbar Vertebrae

2