Prior to the discovery of insulin, carbohydrate restriction was a primary course of treatment for diabetes (1). Previous research, including research highlighted on CrossFit.com, has repeatedly indicated excess carbohydrate intake is a cause of obesity and diabetes, and a reduction in carbohydrate intake can improve glycemic control and in some cases resolve diabetes entirely (2). This small trial tested the impact of a low-carbohydrate diet in a general practice environment in Southport, U.K.

Nineteen diabetic patients were recruited in the course of general clinical practice. All patients were diabetic and chose to enter the trial when asked (i.e., were self-selected).

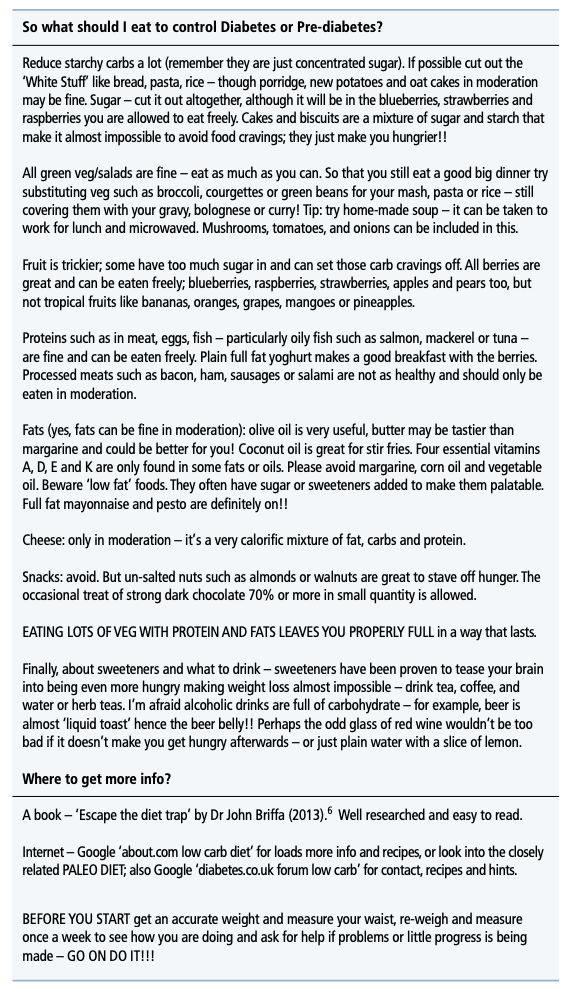

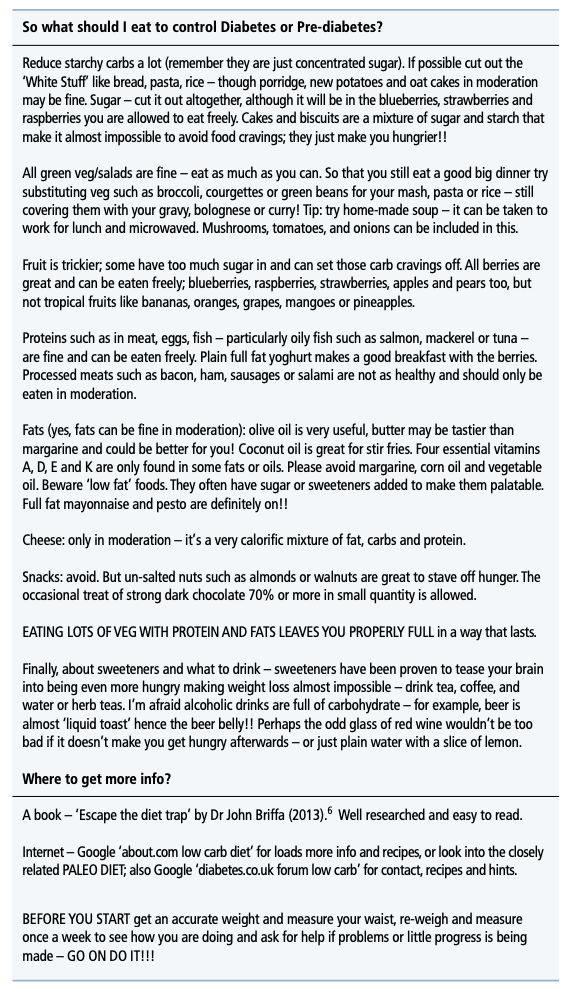

At enrollment, patients were given a diet sheet describing a low-carbohydrate diet that emphasized removing sugars and grains as much as possible while consuming vegetables, protein, and fats. Patients were told to eat as dictated by hunger and not to deliberately reduce calorie intake. An example diet sheet is posted below.

An example of the dietary advice sheet provided to patients

Of the 19 subjects, 18 completed the eight-month study period; the one dropout chose to discontinue the diet based on taste preferences. Among the 18 remaining subjects, mean weight loss was 8.6 kg, with all 18 losing weight. Mean HbA1c decreased from 51 mmol/mol to 40, and 16 of 18 patients were no longer diabetic at the study’s conclusion. Mean blood pressure decreased (systolic: 148 to 133 mmHg; diastolic: 91 to 83 mmHg), as did total cholesterol. As a result of these and other improvements, seven of 18 patients were free of all medications by the end of the study.

Qualitatively, subjects consistently reported improved well-being and energy levels while on the diet. Subjects similarly reported they were not hungry while following the diet, with multiple subjects surprised they had lost weight given the absence of hunger.

These results are consistent with those reported in a previous 44-month study, which found a similar 1.1% improvement in HbA1c among 16 diabetics following a low-carbohydrate diet for 44 months (3).

The authors of this study argue their results support mechanistic evidence indicating carbohydrate restriction reduces fat content in the liver and pancreas, which then supports the restoration of function within these organs and with it glycemic control (4).

This trial has significant limitations: It used self-selecting subjects, dietary compliance was not tracked, and there was not a control group. As such, it fails to meet the standards of a rigorous clinical trial and cannot provide insight into the specific impact of a low-carbohydrate diet on diabetes progression relative to other diets.

It instead provides real-world evidence that a low-carbohydrate diet, without deliberate calorie restriction, can lead to significant improvements in glycemic control in a majority of compliant subjects. In many cases, these improvements will be sufficiently large to reverse a diagnosis of diabetes. This provides additional support for the use of a low-carbohydrate diet in clinical practice, particularly given the inability of standard-of-care approaches to support a durable return to metabolic health. Additional research will continue to help us understand the generalizability, consistency, and potency of these effects across a variety of diets, treatment designs, and populations.