The wonder of Ancel Keys is how, in the absence of definitive proof and despite a mountain of disproof (2), he was able to “sell” unproven hypotheses, now known to be false, to the U.S. medical and scientific communities and then the rest of the world. These hypotheses have not only survived but been the dominant nutritional paradigm globally for the past 70 years. It begins with Keys’ Damascene moment.

Keys’ Road of Discovery, From Minneapolis-St. Paul to Oxford to Pioppi

Recall that some time after October 1949 (3), Keys experienced his Damascene moment, converting from a skeptic of the role of cholesterol/saturated fat in causing heart disease to the most ardent advocate of this heart disease model in the entire world.

According to Gary Taubes (4, p. 16) and Harvey Levenstein (5, p. 127), Keys’ conversion happened during a conference on malnutrition that he attended in Naples, Italy, in 1951. Levenstein describes the journey that led to Keys’ dramatic conversion:

Keys’s road to Damascus — where he experienced his scientific epiphany — was literally a road. In 1951 he was on sabbatical with his biochemist wife, Margaret, in Oxford, England, which was still plagued by post-war shortages of food and fuel. Winter there, he later recalled, was “dark and cold,” and he and his wife shivered in an un-insulated, drafty house. (5, p. 127)

But then an invitation to attend the conference arrived, “so in February 1952, Keys and his wife loaded some testing equipment into their little car and fled gloomy England, heading south to Naples,” Levenstein writes. On the road, they “barely survived” a “bitter thunderstorm” before “reaching the safety of the tunnel under the Alps connecting Switzerland to Italy.” “When they finally emerged into the brilliant sunshine of Italy,” Levenstein continues, “they stopped at an open-air café, took off their winter clothes, and had their first cappuccino. There, Ancel Keys later recalled, ‘The air was mild, flowers were gay, birds were singing … . We felt warm all over, not only from the strong sun but also from the sense of the warmth of the people’” (p. 127).

Keys had discovered his Shangri-la, his utopia (p. 127). Later he would buy a house in Pioppi, Italy, and devote the rest of his life to promoting what became known as the Mediterranean or Pioppi diet.

At the conference in Naples, a local physiologist made the improbable remark to Keys that the people of Naples did not suffer from heart disease. Intrigued, Keys decided to investigate. Together with his wife, whose special expertise was the ability to measure blood cholesterol concentrations, Keys investigated the eating patterns and cholesterol levels of a group of workers in Naples, comparing their results with those from wealthier members of the Naples Rotary Club who typically ate more meat.

When the data showed the Rotarians had higher blood cholesterol concentrations and, after Keys had been informed that the wealthy Neapolitans were more likely to develop CHD, his mind was made up. Clearly rich people developed more heart disease because they ate more fat and therefore had higher blood cholesterol concentrations. Since he knew cholesterol was found in atherosclerotic plaques in humans and high-cholesterol diets caused (a form of) atherosclerosis when fed to herbivorous rabbits (6, p. 5), he instantly thought he understood what was happening. An expensive diet high in animal fats caused blood cholesterol levels to rise in humans. Given enough time, high blood cholesterol concentrations would ultimately cause “clogging” of the coronary arteries, leading to fatal heart attacks. Problem solved.

The subsequent publication of the data showing mortality from heart disease fell in a number of Scandinavian countries during World War II coincident with a reduction in the consumption of fat- and cholesterol-rich foods from animal sources further convinced him of the direction his future research should follow (3).

The timing of his Damascene moment was also perfect for Keys; he was in the right place at absolutely the right time. His conversion happened shortly after President Harry Truman had signed into law the National Heart Act, which effectively “opened the floodgates for researchers studying the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of heart disease” (7, p. 220). In his search for a new research direction following the completion of his war-related research during World War II (8), Keys would have been idiotic not to grasp the opportunity.

But Keys knew that to stay ahead of the competition, he had to act fast — in fact, very fast. He did not have the luxury of time to undertake complex studies that would take decades to provide answers. And in any event, the answers might not be those he wanted.

His recently launched Minnesota Business and Professional Men Study (9) was certainly not the answer, for it had not been designed to test for any possible links between diet and heart disease. In any case, it would take years to produce publishable material; years Keys did not have if he wanted to become the dominant figure in the field. He had but a short time, at most a few years, to produce the evidence that would convince the world and, of course, to persuade his peers at the National Institutes of Health that here was a research direction which, when led by him, was well worth pursuing.

Based on his experience with the wealthy and the not-so-wealthy of Naples, he came up with two quite simple, easily understandable and readily testable hypotheses: the diet-heart and lipid hypotheses. Their very simplicity made them particularly attractive to the naïve funding organizations of the day. No need for any complex grasp of biology to understand what Keys was proposing. The simplicity would also make his ideas more easily understandable by the general public, especially when explained in his own terms:

The most important point about the diet … is that the fats we eat have a major effect on the amount of cholesterol in the blood, and it is the cholesterol which is deposited in the walls of the arteries. The more common fats in our American diet — meat and dairy fat, margarine and hydrogenated shortenings — tend to raise the blood cholesterol (concentration). On the other hand, most common foods (liquid fats) generally have no such effect or may work in opposition. (6, p. 14)

Then, when he discovered the WHO data on coronary heart disease (CHD) rates and national dietary fat intakes (3, Figure 5), he must have known he’d hit the scientific jackpot. There, he found gifted to him all the information he needed to make his diet-heart hypothesis appear credible. By carefully selecting the most graphically convincing pieces of that information (3, Figure 4), he would have known that he (and he alone) would be able to convince everyone of importance that these associational data were good enough to prove causation. All he needed was his well-demonstrated ability to attract publicity for his scientific ideas, as well as his developing skill at convincing and then managing others so that they all saw the scientific “evidence” exactly as he did. His ultimate goal would be to build and reward a team of like-minded individuals, in part by including them in the multi-country study, the Seven Countries Study (SCS), for which he had acquired substantial funding.

Early on, Keys must have realized that without training in medicine and without any clinical experience in treating patients with heart disease, few would take his ideas seriously. To advance his ideas into the mainstream, he ultimately needed the support of someone with real gravitas in medicine, but especially in cardiology. Who better to do that for him than the world’s preeminent cardiologist of the day, Dr. Paul Dudley White (10), the man who, quite conveniently, was one of the founders of the American Heart Association, had assisted President Truman with the establishment of the National Heart Institute in 1948, and would become one of the driving forces behind the SCS. As Nina Teicholz remarks, “White’s influence in the field was nearly boundless” (1, p. 32). Keys exploited that influence to its limits.

While Keys was completing his studies in Cape Town, Naples, and Madrid (3), he hit on the idea of convening a meeting of the world’s foremost international experts in Naples in 1954. The goal of the meeting was to come up with a coordinated plan for future epidemiological studies of heart disease in different countries.

Since he knew White was due to chair the 1954 International Society of Cardiology (ISC), it was logical for him to invite White also to the Naples meeting. Judging from White’s personality, I suspect he would have been flattered by the invitation and seen it as another opportunity to advance both his influence and his crusade to reverse the CHD “epidemic.” This is not to say that White was ego driven, just that he felt (like many of us) that he had an important message to convey to the world, and he would have seen this as an ideal opportunity to advance that message.

One result was that White turned the ISC meeting into a forum for research, with Keys’ theory serving as the main focus. Thus, as Levenstein writes, “In the inaugural session, White and Keys presented their argument to 1,200 doctors packed into a hall that sat 800” (5, p. 129). The event was widely reported in the media; The New York Times proclaiming as fact that “specialists from around the world “agreed that high-fat diets, which are characteristic of rich nations, may be the scourge of Western civilization. The diets were linked with hardening of the arteries and degeneration of the arteries” (5, p. 129).

In the following spring (1955), White again joined Keys, this time in Cagliari, Sardinia (11), where he observed people consuming “a diet very low in meat, loaded with fruit and green vegetables, bread and pasta, liberally sprinkled with olive oil” (p. 212). This diet, he was able to show, was associated with low blood cholesterol concentrations and low rates of heart disease, just as his hypothesis predicted.

Then, from Sept. 7-9, 1955, just two weeks before Eisenhower’s heart attack, White was one of a select group of scientists and doctors invited to attend the Minnesota Symposium on Atherosclerosis in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Naturally, Keys was the key member of the organizing committee (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Five participants in Ancel Keys’ Minnesota Symposium on Atherosclerosis, Sept. 7-9, 1955, admiring a newspaper article presumably reporting on their symposium. From left: H. Malmros (Lund, Sweden), P. D. White (Boston, Massachusetts), F. Rondeau, A. Keys (Minneapolis, Minnesota), J. Brock (Cape Town, South Africa). At the Symposium (12), Malmros reported on the “remarkable” changes in the frequency of atherosclerosis in Scandinavian countries during World War II (13); Brock, who was Professor of Medicine when I entered the University of Cape Town Medical Faculty in 1969, spoke about his collaborative Cape Town study with Keys (14). (As an aside, perhaps one of the reasons for the vitriolic attacks (15) to which I was subjected by that same university’s faculty after I began to question the diet-heart and lipid hypotheses (16) could have been the 62-year-long intellectual investment the faculty have made in Keys’ hypotheses. Reading Keys’ book (6) made me appreciate that most of the themes currently taught to medical and dietetics students in that faculty could still come directly from Keys’ book, written 57 years ago.)

Keys exploited the opportunity to use “quotation and repetition of the suggestive association” to advance his hypothesis:

I believe that a powerful effect of the diet on human atherogenesis can no longer be doubted. Though it is easy to point to many unanswered questions about the effect of the diet, it is more and more clear that there is a broad interrelationship between the dietary fats, the concentration of cholesterol, especially that in the beta lipoprotein fraction of the serum, and the development of atherosclerosis. In any case, in the effect of the mode of life must be our hope for the future. I think we can be confident that this hope is well founded. (12)

The result was that by the time White was summoned to Eisenhower’s bedside on Sept. 25, 1955 (17), despite what he had previously written in his 1946 textbook, the cardiologist seems to have been largely won over by Keys’ twin hypotheses (5, p. 129) — although, it seems, not completely.

In 1956, a year after Eisenhower’s heart attack, White participated in an American Heart Association (AHA) fundraiser that aired on all three major U.S. television networks and was designed to launch the AHA “Prudent Diet,” which advocated the replacement of butter, lard, beef, and eggs with corn oil, margarine, chicken, and cold cereal. There, as Mary Enig and Sally Fallon write:

White noted that heart disease in the form of myocardial infarction was non-existent in 1900 when egg consumption was three times what it was in 1956 and when corn oil was unavailable. When pressed to support the Prudent Diet, Dr. White replied: ‘See here, I began my practice as a cardiologist in 1921 and I never saw an MI patent until 1928. Back in the MI-free days before 1920, the fats were butter and lard, and I think that we would all benefit from the kind of diet that we had at a time when no one had ever heard the word corn oil. (18, p. 20)

Interestingly, White was the co-author of a paper published in 1950 (19) that investigated the hypothesis that “the prevalence and increasing incidence of coronary artery disease in the United States in the past decade” could be attributed “to the allegedly high ingestion of cholesterol in the diet” (p. 696). The authors were especially concerned that incomplete evidence was being touted “as evidence of an inescapable causal relationship between elevated serum cholesterol and atherosclerosis” (p. 696, my emphasis).

To test this hypothesis, they measured blood cholesterol concentrations in 229 subjects, 90 of whom had suffered a documented heart attack before the age of 40. The diets of all subjects were also studied.

The key finding was that despite a lower dietary cholesterol intake, the heart attack survivors had significantly higher blood cholesterol concentrations. Dietary fat intake was also lower in the heart attack survivors.

The authors noted there was “a startling independence of ingested cholesterol and serum cholesterol in the two groups studied” (p. 701) and concluded “serum cholesterol is independent of dietary cholesterol with normal limits of ingestion” (p. 702).

As a result, they wrote, “From the evidence submitted it is believed that not only is a low cholesterol diet of questionable value in the treatment of coronary artery disease, but there is complete independency of the level of serum cholesterol and the amount of cholesterol ingested within the normal dietary variations” (p. 703).

They added: “The question is raised as to the wisdom of removing cholesterol from the diet of individuals with coronary artery disease. From the evidence gathered from this study and other dietary studies in this laboratory, it is believed that there is no advantage to be gained from imposing a low cholesterol diet on patients with coronary artery disease” (p. 703).

However, White’s misgivings were never enough to again cause him seriously to doubt or challenge Keys’ hypotheses, or to question the value of the low-fat, low-cholesterol diet he would prescribe to President Eisenhower on the advice of Keys (17) — or, apparently, to entertain Dr. George Mann’s criticism of Keys’ arguments based on his and others’ associational studies: “The naivete of such an interpretation of associated attributes is now a classroom demonstration,” Mann wrote (20, p. 644).

White’s dedication to Keys’ hypotheses became apparent after President Eisenhower had returned to the White House in January 1956. Then, White wrote a nationally syndicated newspaper article for The New York Times, giving his “reflections” on the President’s heart attack. Echoing Keys’ sentiments, White declared the cause had little to do with stress. Instead, he claimed, it was likely due to the president eating too much fat: “‘The brilliant work of such leaders as Ancel Keys had shown this to be a major cause of coronary thrombosis’” (5, p. 129-130). This statement establishes White had also experienced a Damascene moment some time between 1950 and 1956, the cause of which is unknown.

I would suggest the probable explanation is that after 1952, Keys had worked unceasingly on White until he too became an active supporter and advocate of Keys’ still unproven hypotheses.

Teicholz makes the point that Keys was the only researcher White mentioned by name in the article, and “his is the only dietary theory that is quoted at length. If a middle-aged American man learned nothing else from the entire presidential episode, it was that the country’s top doctors believe the public should cut back on dietary fat” (1, p. 33).

It is clear that by 1956, Keys’ capture and conversion of the most influential cardiologist in the world was then complete. Keys’ ascent was unstoppable.

By that year, Keys was arguing the conventional explanations for the causes of CHD, including racial origin, body build, smoking habits, and stress and strain, were largely wrong. Instead, the only factors that mattered were lack of physical exercise and the percentage of fat in the diet (5, p. 130). According to Keys, the clinching piece of evidence was obvious. It was that Yemenite Jews suffered no heart disease in Yemen, but when they moved to Israel and began to eat the high-fat diet of the locals, their heart disease rates soared.

Interestingly, this establishes that by 1956, Keys had mysteriously forgotten that, in truth, it was the publications of J. W. Gofman and colleagues (21), and reports of falling CHD mortality rates in the Scandinavian countries during World War II (13) that had originally inspired him to formulate his diet-heart hypothesis (3). Perhaps by 1956, he had realized that if he continued to draw attention to that work, especially the work of real lipid scientists like Gofman and his colleagues (21), he would lose the right to claim priority for the development of “his” diet-heart and lipid hypotheses (3).

But not for the first time in his life, Keys came to the wrong conclusion based on his simplistic interpretation of a single observation.

Two studies, published in 1961 and 1963, found that increased sugar intake, not fat, was the more likely explanation for the phenomenon seen in the Yemenites. The authors of the first wrote, “It is suggested that the greater use of sugar may be connected with the increase in incidence of ischaemic heart disease and diabetes mellitus among long-settled Yemenites compared with recent immigrants” (22, p. 1399). And the authors of the second: “If a nutrient is an etiological factor underlying the increased incidence of atherosclerosis and diabetes in Yemenites who have lived in Israel for many years, it seems that suspicion must fall on the ingestion of sucrose. The increased consumption of sucrose might, therefore, also be responsible for the increased prevalence of these diseases in the general population” (23, p. 293).

What Keys failed to grasp was that when living in the desert, the Yemenites lived on fats that “were mainly or solely of animal origin: ‘Samme’ (dehydrated butter), milk, mutton, beef, and very few eggs; vegetable oil was rarely used” (23, p. 292). But in Israel, the settlers consumed the same amount of animal fat “together with margarine (40 to 50 Gm. daily) and, in addition, about 30 Gm. of vegetable oil (soya, sesame, and olive).”

The nature of the carbohydrates eaten were also different. In the desert, the Yemenites’ intake “consisted solely or mainly of starches; almost no sugar was used. In Israel, sucrose accounted for 25 to 30 per cent of the total carbohydrate” (p. 292).

Keys also failed to mention that the Bedouins in Israel who also ate animal fat when they lived in the desert likewise began to develop CHD when they replaced the animal fats with vegetable fats (and sugar) after moving into the Israeli towns (22, p. 41).

But saturated fat, not sugar or vegetable fats, was the villain Keys was pursuing (3).

The effect of the Time magazine article was to present Keys’ hypotheses to the world as if they were proven facts: “The piece read as if Keys and White had already won the argument” (5, p. 130).

Yet there would still be some internal resistance from the AHA that Keys would need to neutralize.

In August 1957, five AHA physicians felt it necessary to write an article to assist physicians who were increasingly under pressure “to do something about the reported increased death rate from heart attacks in relatively young people” (25, p. 164).

In a comment clearly directed at Keys’ activism, they noted, “On the one hand, some scientists have taken uncompromising stands based on evidence that does not stand up under critical examination” (25, p. 164). They continued: “In the opinion of the authors of this review, there is not enough evidence available to permit a rigid stand on what the relationship is between nutrition, particularly the fat content of the diet, and atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease” (p. 164).

They concluded: “Perhaps the best that can be said is that there is an association that has statistical value, but that is not an obligatory association either in small groups or, as much less so, in an individual” (p. 174). As a result, they claimed, “The evidence at present does not convey any specific implications for drastic dietary changes, specifically in the quantity of fat in the diet of the general population, on the premise that such changes will definitely lessen the incidence of coronary or cerebral disease” (p. 175). Instead, there was a need for more research, they argued.

Keys clearly faced some challenges that he could not solve immediately by providing additional scientific evidence, so he chose a more pragmatic approach; one in which he was uniquely skilled.

The result was that in 1961, without any additional and novel scientific evidence, the AHA changed its tune. Suddenly, a different Central Committee for Medical and Community Program of the American Heart Association, which included Keys and his buddy Dr. Jeremiah Stamler from the MRFIT study, recommended:

The reduction or control of fat consumption under medical supervision, with reasonable substitution of poly-unsaturated for saturated fats, is recommended as a possible means of preventing atherosclerosis and decreasing the risk of heart attacks and strokes. This recommendation is based on the best scientific information available at the present time. (26, p. 390)

And what was the quality of that information? Well, the authors were clear on that point:

A reduction in blood cholesterol by dietary means, which also emphasizes weight control, may lessen the development or extension of atherosclerosis and hence the risk of heart attacks or strokes. It must be emphasized that there is as yet no final proof that heart disease or strokes will be prevented by such measures. (p. 390)

This statement carefully matched the disclaimer included in the preface to Keys’ book:

It is still not proved by rigorously controlled large-scale experiments on statistically impeccable samples of the American population that the kind of dietary adjustment suggested in this book will actually prevent or lessen the risk of heart attacks. The extraordinary difficulties of such experiments may mean the ultimate, irrefutable proof can never be provided. (6, p. vi)

This statement is as true today (1, 27) as it was in 1961. The problem was that Keys never accepted the disclaimer. As Levenstein writes, “He himself was convinced that saturated fat in the diet caused heart disease” (5, p. 135). And that is what he told The New York Times on Dec. 12, 1961 (5, p. 199).

The truth is that the sole reason the AHA changed its opinion of Keys’ hypotheses was simply that Keys personally ensured that the 1961 Central Committee for Medical and Community Program was dominated by those members whose opinions agreed with his. Certainly, there was no new evidence to support that change. Mann commented, “Two of the authors of the 1961 recommendation were Keys and Stamler, who were both, for whatever reasons, committed to the diet-heart hypothesis. Keys holds a PhD in physiology and Stamler is a medical doctor with some training in pathology. Neither is trained in cardiology, epidemiology, or nutritional science” (28, p. 5).

It was, however, a decisive victory for Keys. In fact, it was the tipping point in the acceptance of his unproven hypotheses as established facts. As a result, for the next five decades, Keys’ hypotheses remained beyond challenge, beyond reproach — at least, until the publication of two seminal books, written not by medical scientists but investigative journalists (1, 4), whose powerful messages could not be censored or controlled by either the AHA or the NHLBI.

As Teicholz (1) has written, “The 1961 AHA report was the first official statement by a national group anywhere in the world recommending that a diet low in saturated fat be employed to prevent heart disease. It was Keys’ hypothesis in a nutshell” (p. 50).

Two weeks after the release of the AHA Central Committee report, Keys was featured on the cover of Time magazine. The article (29), which referred to Keys as “Mr. Cholesterol,” detailed the diet-heart hypothesis and highlighted Keys’ advice to cut dietary fat: “The only sure way to control blood cholesterol effectively, says Keys, is to reduce fat calories in the average U.S. diet by more than one-third (from 40% to 15% of total calories), and take an even sterner cut (from 17% to 4% of total calories) in saturated fats” (29, p. 7).

“His diet recommendations are fairly simple,” Time reported. “‘Eat less fat meat, fewer eggs and dairy products. Spend more time on fish, chicken, calves’ liver, Canadian bacon, Chinese food, supplemented by fresh fruits, vegetables and casseroles’” (p. 7).

Keys’ stern warning was very clear: “People should know the facts. Then, if they want to eat themselves to death, let them” (p. 7).

Keys had won the battle for the minds and hearts of those in his profession and the general public.

To further promote his message to the general public, at the same time he released his popular book, Eat Well and Stay Well (6), which would become a national bestseller.

Keys releases a bestselling book to bring his message of lipophobia to the rest of the world

In 1959, Keys released the first edition of his book, which provided a popular account of his hypotheses (6), supplemented with more than 120 pages of recipes and a foreword by White. The foreword is remarkably guarded and fails to make any great endorsement of Keys’ ideas (in my opinion).

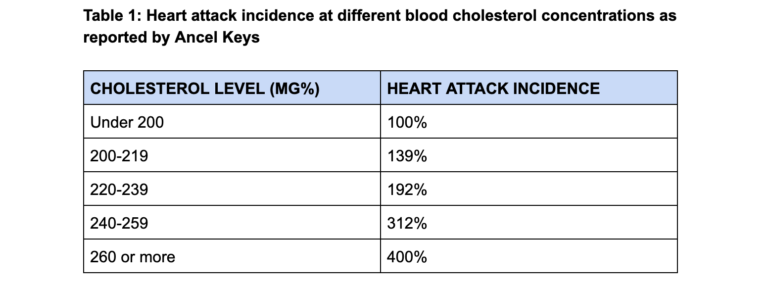

In the second edition of the book, published in 1963, I found the following table (p. 18):

Keys claims the data comes from three different studies — Albany, New York; Framingham, Massachusetts; and Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota — but he gives no reference to the actual studies or the original data from which he made these deductions.

Keys interprets the data as proof that “men with cholesterol values over 260 have four times as much risk as those with values under 200” (p. 18).

His calculations refer to an increase in relative risk. But if the absolute risk for developing CHD is low, then even a four-fold increase in relative risk does not increase absolute risk substantially. The increase is a mere 0.6% to 2.4% according to the example from the Framingham data (30), as discussed in a previous column (2).

Certainly, a 2.4% risk sounds substantially less frightening than a 400% risk!

But the real truth of this relationship is that which is presented earlier in Figures 1, 3, and 4 in a previous column (2). Those figures show that any contribution a rising blood cholesterol concentration makes to increasing CHD risk is, at the very most, essentially trivial.

But Keys’ book, with its foreword from President Eisenhower’s cardiologist, predicted a 400% increase in risk of CHD with rising blood cholesterol concentrations. In the minds of all who read it, this statement would have established Keys’ hypothetical ideas as established facts. The public would not stop to ask whether anyone would dare to make such a dire prediction without being absolutely certain of the facts. The assumption was that Keys had to be the expert. He had to know what he was talking about.

So Keys’ book unleashed a global mania of lipophobia, a fear of dietary fat (5, p. 125-138), as well as an international eating disorder (5, p. 139-159).

The book identified Keys not as a scientist searching after a complex and difficult truth but as an activist driven by a specific (non-scientific) agenda. He had become an activist. His book, he admitted, had been written to “wage war on cholesterol” (5, p. 132).

The preface to Keys’ book carried the disclaimer that science had yet to prove the diet he was recommending actually does “prevent or lessen the risk of heart attacks” (6, p. vi).

But in the absence of such definitive proof, Keys experienced no personal misgivings that he was promoting an untested and unproven dietary intervention that might have adverse consequences to global health.

In the end, Keys believed his own hubris. When the 1961 Central Committee for Medical and Community Program for the AHA released its report (26), Keys complained that the following sentence was inserted against his will: “It must be emphasized that there is as yet no final proof that heart disease or strokes will be prevented by such measures” (26, p. 389). He himself was fully convinced that saturated fat caused heart disease (5, p. 135).

Keys ignores the failed dietary experiment of President Eisenhower

Keys’ history proves he was always very keen to draw sweeping conclusions from simple, untested observations, provided those observations supported his hypotheses.

The evidence that CHD mortality dropped in certain countries during World War II (13, 31-33) convinced Keys (34) that war rations, which reduced fat and increased dietary carbohydrate intake, produced a reversal of atherosclerosis as a result of falling blood cholesterol concentrations. But this conclusion is only one of many possible explanations.

As I wrote earlier (3), A. Strom and R. A. Jensen specifically warned that associational data do not prove causation — a qualification that would go missing once Keys took charge of “his” hypothesis: “We must, however, beware of regarding the evidence as decisive. Similar correlations could undoubtedly be demonstrated between mortality and trends in other commodities, such as sugar, coffee, tobacco, textiles, and footwear; yet the last two of these can hardly have exerted any influence on mortality” (31, p. 128, my emphasis).

Indeed, the reduction in severe atherosclerosis observed at post-mortem in Finland (35) was much less than the decline in mortality, which indicates war likely “protects” against mortality (in the civilian population) either by protecting against fatal heart rhythm disturbances (arrhythmias) or reducing the likelihood of atherosclerotic plaque ruptures leading to coronary artery thrombosis (36). Neither of these effects necessarily requires any diet-induced reduction in blood cholesterol concentrations, a point ignored by Keys.

The second example of Keys’ rapid adoption of new evidence that would support his evolving hypotheses occurred during his dinner with the wealthy members of the Naples Rotary Club in 1951 (3). This provided evidence from an opposite, “natural” experiment. Keys interpreted that evidence as proof that coronary atherosclerosis developed as a result of the action on the coronary arteries of high blood cholesterol concentrations in those eating a rich person’s diet full of animal fats.

Then in 1961, Keys gave the editors of Time magazine (29) another observation he believed provided definitive proof for his hypothesis: the evidence that Yemenite Jews developed CHD when they moved to Israel and began to eat a diet full of animal fats (actually full of sugar!).

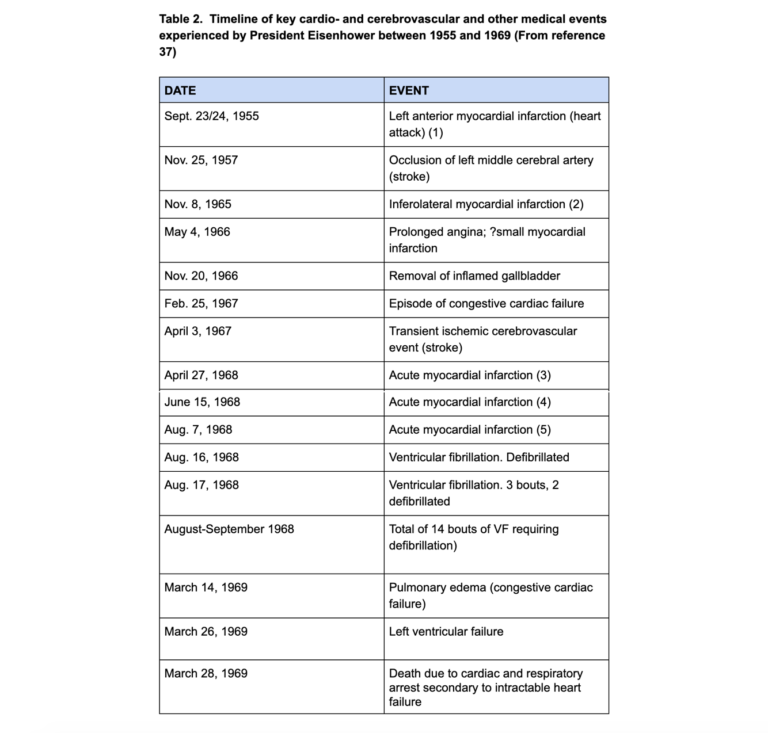

This raises the crucial question: Why did Keys not draw any immediate conclusions from the clearly detrimental effects his experimental, untested, low-fat, low-cholesterol, high-carbohydrate diet was having on the future health of President Eisenhower after that diet had been prescribed to the president in September 1955 (17, 37)?

Here is the timeline of how the president fared on the diet Keys promoted as the only one that can prevent the progression of CHD.

Recall (17) that at autopsy, Eisenhower’s heart showed “atherosclerotic occlusive disease, multifocal, severe, with multiple recanalized thrombi” (37, p. 321). Of the three major coronary arteries, only the right coronary artery was patent; the left anterior descending coronary artery had 10% narrowing in various sections; the circumflex artery was totally obstructed in several sections.

During the time that his most famous experimental subject was experiencing this progression of his cardiac disease, Keys twice appeared in prominent media campaigns in the U.S. (1956 and 1961), berating U.S. citizens for not eating his low-fat, low-cholesterol diet; he published his book (1958 and 1963), which introduced the world to lipophobia and the fear of cholesterol; he ensured that the AHA changed its guidelines (1957-1961) to give the definitive stamp of approval to his hypotheses; and he sought funding for and initiated his two key experiments, the SCS in 1956 (38) and the MCE in 1968.

At no time during this period did Eisenhower’s worsening health ever cause Keys to question the validity of what he was doing. Or, if it did, it never caused him to alter course or question the validity of his dietary activism.

Keys’ failure to respond to the worsening of the president’s health without questioning the probable role of the low-fat, low-cholesterol diet he had prescribed is a textbook example of “negative evidence,” to which I referred in an earlier column (39).

Recall from Sherlock Holmes’ story, The Adventures of Silver Blaze:

The fact that the dog did not bark when you would expect it to do so while a horse was stolen led Holmes to the conclusion that the evildoer was not a stranger to the dog, but someone the dog recognized and thus not cause him to bark. Holmes drew a conclusion from a fact (barking) that did not occur, which can be referred to as a ‘negative fact,’ or for the purposes of this discussion, an expected fact absent from the record. (40)

Keys’ failure to act on the clear evidence that Eisenhower’s health deteriorated progressively while eating a diet that had been prescribed by White on the recommendation of Keys specifically to prevent any deterioration in the president’s coronary artery disease is clearly “an expected fact absent from the record.”

Given that he was wrong, how did Keys’ ideas take the world by storm?

A number of writers have pondered this question: How did Keys’ wrong ideas come to dominate the medical world? The evidence is clear: Once Keys had convinced White to change his opinions about the relationship between diet, cholesterol, and coronary heart disease (18,19), and had engineered the support of the AHA in 1961 (26) to promote his diet, there was no turning back. The horse had indeed bolted.

1. Nina Teicholz (1) writes:

The nucleus of control steering these groups (American Heart Association (AHA) and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI)) was a tiny group of experts with overlapping responsibilities. The number of those in this nutritional elite was small enough for them all to be on a first name basis with each other and they came to control pretty much every large clinical trial on diet and disease. They were the nutrition ‘aristocrats,’ to use a term coined by Thomas J. Moore, a journalist who wrote an explosive critique of the cholesterol hypothesis in 1989 (41). They came from the academic faculties of medical schools, teaching hospitals, and research establishments, mainly along the Eastern Seaboard but also in Chicago … . The group of nearly all men worked closely with the AHA and the NHLBI. Members of this academic haut monde were appointed to official committees and expert panels; they co-authored influential articles, sat on the editorial boards of major scientific journals, and peer-reviewed each other’s papers. They attended and dominated the major professional conferences …

The AHA and NHLBI together also administered the vast majority of grants for all cardiovascular research. By the mid-1990s, the NHLBI’s annual budget had reached $1.5 billion, with most of those funds going to heart disease research; the AHA, meanwhile, was devoting about $100 million a year toward original research. These two pots of money dominated the field …

Ultimately, for every million more dollars spent by the AHA and NIH trying to prove the diet-heart hypothesis, the harder it became for those groups to reverse course or entertain other ideas. Although studies on the diet-heart hypothesis had a surprisingly high failure rate, these results had to be rationalized, minimized, and distorted, since the hypothesis itself had become a matter of institutional credibility …

The dissenting voices were fading … In the pages of sympathetic scientific journals, [Edward] Ahrens and Mann, plus their handful of like-minded colleagues, continually set up futile cries against the relentless march of the diet-heart hypothesis, but they were powerless in the face of the elite. (pp. 69-71)

2. Mann (43) writes:

Keys and his crowd need a long visit to the confessional. Since the erroneous Diet-Heart myth is supported and propagated by the National Institutes of Health, which supplies over half the biomedical research money, supporting Diet-Heart dogma has become a way to get research money. The so-called Study Section system of reviewing research applications is a stacked deck. Believers are supported, non-believers are not. (p. 215)

Mann speaks from experience. Like Professor John Yudkin (44), once Mann identified himself as a “non-believer,” he lost all his research funding: “The critical strategy of my career has been my opposition to what has come to be called the ‘Diet-Heart’ theory. By opposing this I have been denied research funding by the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and other important foundations” (42, p. 210).

Mann continues:

For 25 years the treatment dogma for coronary heart disease (CHD) has been a low-cholesterol, low-fat, polyunsaturated diet. This treatment grew out of a reasonable hypothesis by Gofman and others, but soon a clot of aggressive industrialists, self-interested foundations, and selfish scientists turned this hypothesis into nutritional dogma which was widely impressed upon physicians and the general public. A nadir was reached when zealous doctors and salesmen arranged such “prudent” meals for national meetings of cardiologists, rather like Tupperware teas. There grew up in the interface between science and the government funding agencies a club of devoted supporters of the dogma which controlled the funding of research, a group known by the cynics among us as the “heart Mafia.” Critics or disbelievers of the diet/heart dogma were seen as pariahs and they went unfunded, which such extravagancies as the Diet/Heart trial, the MRFIT trial, and a dozen or more lavish Lipid Research Centers divided up the booty. For a generation, research on heart disease has been more political than scientific. All this resulted from the abuse of scientific method. A valid hypothesis was raised, tested, and found untenable. But for selfish reasons, it has not been abandoned. T. C. Chamberlin, the American geologist, and philosopher, described the situation succinctly in 1897 (45, p. 755):

The moment one has offered an original explanation for a phenomenon which seems satisfactory, that moment affection for his intellectual child springs into existence; and as the explanation grows into a definite theory, his parental affections cluster about his intellectual offspring and it grows more and more dear to him … . There springs up, also, an unconscious pressing of the theory to fit the facts and pressing of the facts to make them fit the theory. When these biasing tendencies set in, the mind rapidly degenerates into the partiality of paternalism.

3. R. L. Smith and E. R. Pinckney (46) write:

The diet-CHD issue was elevated to national prominence in 1976 and 1977 when a U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs convened. Chaired by Senator George McGovern, the primary testimony at the hearings was that of Dr. Robert Levy, Director of NHLBI. Although he readily admitted that no scientific evidence existed which showed that CHD can be reduced by diet or by lowering blood cholesterol by any means, he nevertheless urged Congress to recommend the Prudent Diet for everyone. McGovern’s Committee agreed …

Nothing would now stop NHLBI and AHA from convincing all Americans. When the American Medical Association reversed its 1972 position and published a statement in 1977 opposing the Prudent Diet, it was promptly rejected (47). When the American Society for Clinical Nutrition concluded in 1978 that the evidence linking diet with CHD was “unconvincing,” that conclusion was promptly rejected (48). And when the National Academy of Sciences reversed its 1972 opinion after reviewing the research literature in 1980, it was promptly rejected (49). (p. 20)

4. Terence Kealey (50) writes:

Once armed with power over government-funded research grants, access to peer-reviewed journals and appointments to university positions, Keys and his fellow elite researchers could enforce their paradigm on the whole field. Which was why the successful paradigm-shifter emerged not as a mainstream scientist but as a journalist – Taubes – who was spared the pressure to conform. And this public-choice aspect of science was aggravated by the Senate Select Committee’s endorsement of the fat paradigm, which fuelled it, literally, with public money. (p. 27)

5. Todd Olszewski (7) writes, “Despite the static and often vitriolic debate over approximately thirty years, it ironically became irrelevant as policymakers hurried to endorse a hypothesis that had already become clinical and public health orthodoxy” (p. 249). Of course, this would have been helped immeasurably by the publication of Keys’ book in 1958 (6).

6. Adele Hite (53) provides a historical perspective on why the 1977 Dietary Guidelines (54), the ultimate product of Keys’ activism, could have happened:

The creation of the Dietary Goals signalled a turning point in the kind of dietary guidance that the U.S. federal government would endorse and promote. The shift from advice to acquire adequate essential nutrition, to advice that was meant to prevent chronic disease emerged from a backdrop of sweeping historical changes, including the growth of nutritional epidemiology of chronic disease, the expansion of commodity crop-based agribusiness, and the rise of healthism and the related politics of neoliberalism. The shift incorporated strategic logics descended from earlier patterns of thinking in nutrition science that characterized the human body as a machine and suggested that undetectable factors in food (or the lack thereof) could lead to vaguely defined illness. Both patterns of thinking reflected ideas about the body as knowable and controllable and about nutrition as a strategy for solving social problems. The kind of dietary advice that was presented in the Dietary Goals was also a response to a number of specific historical events, including the spectre of potential world food shortages; the discovery of links between smoking and lung cancer; the public health focus on prevention through alterations in lifestyle; and the need for McGovern’s committee to justify its existence. Against the backdrop of other broad historical changes and the logics inherited from earlier nutrition science, these events served as more proximal exigencies for the development of dietary guidance for prevention of chronic disease. (p. 97)

In sum, Keys, it seems, was at the right place at the right time if he wanted to become “the Greatest Man” (1, p. 46) in the history of the nutritional sciences. And he executed his plan perfectly.

But perhaps history is finally catching up with him.

ADDITIONAL READING

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 1

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 2

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 3

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 4

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 5

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 6

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 7

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 8

- It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 9

Professor T.D. Noakes (OMS, MBChB, MD, D.Sc., Ph.D.[hc], FACSM, [hon] FFSEM UK, [hon] FFSEM Ire) studied at the University of Cape Town (UCT), obtaining a MBChB degree and an MD and DSc (Med) in Exercise Science. He is now an Emeritus Professor at UCT, following his retirement from the Research Unit of Exercise Science and Sports Medicine. In 1995, he was a co-founder of the now-prestigious Sports Science Institute of South Africa (SSISA). He has been rated an A1 scientist by the National Research Foundation of SA (NRF) for a second five-year term. In 2008, he received the Order of Mapungubwe, Silver, from the President of South Africa for his “excellent contribution in the field of sports and the science of physical exercise.”

Noakes has published more than 750 scientific books and articles. He has been cited more than 16,000 times in scientific literature and has an H-index of 71. He has won numerous awards over the years and made himself available on many editorial boards. He has authored many books, including Lore of Running (4th Edition), considered to be the “bible” for runners; his autobiography, Challenging Beliefs: Memoirs of a Career; Waterlogged: The Serious Problem of Overhydration in Endurance Sports (in 2012); and The Real Meal Revolution (in 2013).

Following the publication of the best-selling The Real Meal Revolution, he founded The Noakes Foundation, the focus of which is to support high quality research of the low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet, especially for those with insulin resistance.

He is highly acclaimed in his field and, at age 67, still is physically active, taking part in races up to 21 km as well as regular CrossFit training.

References

- Teicholz N. The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong in a Heathy Diet. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2014.

- Noakes TD. It’s the insulin resistance, stupid: Part 8. CrossFit.com. 24 Nov. 2019. Available here.

- Noakes TD. It’s the insulin resistance, stupid: Part 6. CrossFit.com. 31 Oct. 2019. Available here.

- Taubes G. Good Calories, Bad Calories: Fats, Carbs, and the Controversial Science of Diet and Health. New York: NY: Anchor Books, 2008.

- Levenstein H. Fear of Food. A History of Why We Worry About What We Eat. London, U.K.: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Keys A, Keys M. Eat Well and Stay Well. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1963.

- Olszewski TM. The causal conundrum: The diet-heart debates and the management of uncertainty in American Medicine. J Hist Med Allied Sci 70(2014): 218-249.

- Keys A, Brozek J, Henschel A, et al. The Biology of Human Starvation. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1950.

- Keys A, Taylor HL, Blackburn H, et al. Coronary heart disease among Minnesota business and professional men followed fifteen years. Circulation 28(1962): 381-394.

- White PD. Heart Disease, Third Edition. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1946.

- Paul O. Take Heart: The Life and Prescription for Living of Paul Dudley White, the World’s Premier Cardiologist. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986.

- University of Minnesota. Heart Attack Prevention: A History of Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology. The Minnesota Symposium on Arteriosclerosis, September 7-9, 1955. Available here.

- Malmros H. The relation of nutrition to health. A statistical study of the effect of the war time on arteriosclerosis, cardiosclerosis, tuberculosis and diabetes. Acta Med Scand 246(1950): 137-153.

- Bronte-Stewart B, Keys A, Brock JF, et al. Serum-cholesterol, diet, and coronary heart-disease. An inter-racial survey in the Cape Peninsula. Lancet 269(1955): 1103-1107.

- Noakes TD, Sboros M. Real Food on Trial. How the Diet Dictators Tried to Destroy a Top Scientist. U.K.: Columbus Publishing Ltd., 2019.

- Noakes TD. The 2012 University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences centenary debate. Cholesterol is not an important risk factor for heart disease and the current dietary recommendations do more harm than good. S Afr J Clin Nutr 28(2015): 19-33.

- Noakes TD. It’s the insulin resistance, stupid: Part 5. CrossFit.com. 23 Oct. 2019. Available here.

- Enig MG, Fallon S. The Oiling of America. Part 1. Nexus 6.1(Dec. 1998-Jan. 1999): 19-23; 80-82. Available here.

- Gertler MM, Garn SM, White PD. Diet, serum cholesterol and coronary artery disease. Circulation 11(1950): 697-704.

- Mann GV. Diet-heart: End of an era. N Engl J Med 297(1977): 644-650.

- Gofman JW, Jones HB, Lindgren FT, et al. Blood lipids and human atherosclerosis. JAMA 11(1950): 161-178; Jones HB, Gofman JW, Lindgren FT, et al. Lipoproteins in atherosclerosis. Am J Med 11(1951): 358-380; Gofman JW. Diet and lipotrophic agents in atherosclerosis. Bull NY Acad Med 28(1952): 279-293; Gofman JW, Glazier F, Tamplin A, et al. Lipoproteins, coronary heart disease and atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev 34(1954): 598-607; Gofman JW, Tamplin A, Strisower B. Relation of fat intake to atherosclerosis. J Am Diet Assoc 30(1954): 317-326; Lyon TP, Yankley A, Gofman GW, et al. Lipoproteins and diet in coronary heart disease. A five-year study. Cal Med 84(1956): 325-328.

- Cohen AM, Bavly S, Poznanski R. Change of diet of Yemenite Jews in relation to diabetes and ischaemic heart disease. Lancet 2(1961): 1399-1401.

- Cohen AM. Fat and carbohydrates as factors in atherosclerosis and diabetes in Yemenite Jews. Am Heart J 65(1963): 191-293.

- Enig MG. Diet, serum cholesterol, and coronary heart disease. In: Coronary Heart Disease: The Dietary Sense and Nonsense. An Evaluation by Scientists. Mann GV, Ed. London, England: Janus Publishing Company, 1993. pp.36-60.

- Page IH, Stare FJ, Corcoran AC, et al. Atherosclerosis and the fat content of the diet. Circulation 16(1957): 163-178.

- Ernstene A, Page IH, Allen EV, et al. Dietary fat and its relation to heart attacks and strokes. JAMA 175(1961): 389-391.

- Harcombe Z. An Examination of the Randomized Controlled Trials and Epidemiological Evidence for the Introduction of Dietary Fat Recommendations in 1977 and 1984: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. University of West Scotland, March 2016.

- Mann GV. A short history of the diet/heart hypothesis. In: Coronary Heart Disease: The Dietary Sense and Nonsense. An Evaluation by Scientists. Mann GV, Ed. London, England: Janus Publishing Company, 1993; pp. 1-17.

- Anonymous. Medicine: The Fat of the Land. Time 13 Jan. 1961. Available here.

- Kannel WB, Dawber T, Kagan A, et al. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease – Six-year follow-up experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med 55(1961): 33-50.

- Strom A, Jensen RA. Mortality from circulatory diseases in Norway 1940-1945. Lancet 257(1951): 126-129.

- Pihl A. Cholesterol studies II. Dietary cholesterol and atherosclerosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 4(1952): 122-133.

- Henschen F. Geographical and historical pathology of arteriosclerosis. J Gerontol 8(1953): 1-5.

- Keys A, Anderson JT. The relationship of the diet to the development of atherosclerosis in man. In: Symposium on atherosclerosis. National Academy of Sciences – National Research Council. Washington, DC. Publication 388: 181-196. Available here.

- Vartainen I, Kanerva K. Arteriosclerosis and war-time. Ann Med Intern Fenn 36(1947): 748-758.

- Malinow MR. Regression of atherosclerosis in humans: Fact or Myth. Circulation 64(1981): 1-3.

- Lasby CG. Eisenhower’s Heart Attack: How Ike Beat Heart Disease and Held on to the Presidency. Lawrence, KA: University Press of Kansas, 1997.

- Keys A. Seven Countries: A Multivariate Analysis of Death and Coronary Heart Disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

- Noakes TD. It’s the insulin resistance, stupid: Part 7. CrossFit.com. 12 Nov. 2019. Available here.

- Skotnicki M. “The Dog That Didn’t Bark:” What we can learn from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle about using the absence of expected facts. Briefly writing, July 25, 2012. Available here.

- Moore TJ. The cholesterol myth. The Atlantic. 264(September 1989): 37; Moore TJ. Heart Failure: A Critical Inquiry Into American Medicine and the Revolution in Heart Care. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1989.

- Mann GV. Coronary heart disease – the doctor’s dilemma. Am Heart J 96(1978): 169-171.

- Mann GV. The Way It Seems. Los Angeles, CA: Vantage Press, 1988.

- Leslie I. The sugar conspiracy. The Guardian 7 April 2016. Available here.

- Chamberlin TC. The method of multiple working hypotheses. Science 148(1965): 754-759.

- Smith RL, Pinckney ER. The Cholesterol Conspiracy. St. Louis, MO: Warren H. Green Inc., 1991.

- Anonymous. Dietary goals for the United States: Statement of the American Medical Association to the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, United States Senate. Rhode Isl Med J 60(1977): 576-181.

- Ahrens EH. Dietary fats and coronary heart disease: Unfinished business. Lancet 314(1979): 1345-1348.

- National Research Council. Toward Healthful Diets. Food and Nutrition Board; National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, 1980. Available here.

- Kealey T. Why does the federal government issue damaging dietary guidelines? Lessons from Thomas Jefferson to today. Policy Analysis 10 July 2018. Available here.

- Noakes TD, Proudfoot J, Grier D, Creed SA. The Real Meal Revolution. Cape Town, South Africa: Quivertree Publications, 2013.

- Bateman C. Inconvenient truth or public health threat. S Afr Med J 103(2013): 69-71.

- Hite AH. A Material-Discursive Exploration of “Healthy Food” and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University, 2019. Available here.

- U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs. Dietary Goals for the United States, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1977. More available here.

Comments on It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 10

Thank you for this series, Prof. Noakes. It really closes the circle for me. Coincidently, there is one thing in common for the two of us; the nutritional change started with the book “new Atkins, new you”. I started (unlike you) with zero background, but the book changed everything (including new lite version of me permanently -10kg). After Taubes and Teicholz and many hundreds of other things, this series connects the remaining dots for me.

This phrase is endorsed to several people, but let’s give it to war time German propaganda minister Göring: “if you repeat a lie often enough, the people start believing in it; finally, you believe in it yourself”. Let’s re-dedicate this to Mr. Keys.

The harm his “lies” is still causing to us, is tremendous.

The one mighty commercial force mentioned by Teicholz, P&G and Crisco support to the AHA, bear its fruit the same year Keys started with AHA 1961. Pandoras box for “healthy” poly-un-stable fats was opened, and the devil is still at large. With official recommendation everywhere ever since. Best ever snake-oil marketing…by PUFAgiant P&G.

The unsung hero -close to it -is Reaven; luckily, others have built upon his work, when he kind of gave up halfways. My personal health focus shall be on triglycerides and HDL (and hypertension and belt length) before something trustworthy appears, thanks to this series. If I ever take OGTT again, it must include insulin response, why else bother to drink 75g of glucose?

Seeing the insulin response, a ’la dr. Kraft, reveals the hidden insulin resistance / over-excretion status, long before blood glucose fails.

Thank you once more,

JR

Thanks JR. Hope you enjoy the continuation of this series. Best wishes Tim

It’s the Insulin Resistance, Stupid: Part 10

3