This 2017 narrative review compares the basis and implications of the traditional, calorie-centric understanding of obesity to an alternative concept that positions obesity as a hormonally regulated condition.

The authors refers to “Concept 1” as the model that views obesity as a disease of energy imbalance whereby individuals become fat by eating more calories than they burn. Dietary guidelines are broadly based on this concept and generally recommend obese individuals consume 500 to 750 fewer calories than they expend each day (1). Significantly, an excess of only 175 calories per day would be sufficient to drive 3 kg of annual weight gain (2).

Practically, this guideline is all but impossible to implement. First, we are unable to accurately and precisely assess how many calories an individual actually burns each day — the 175-calorie-per-day excess noted above is within the error bounds of even gold-standard methodologies to assess daily energy expenditure (3). Our ability to assess the number of additional calories burned through exercise and other forms of activity is just as bad, with estimated error of ~100 calories per day (4). And yet, even if we could assess energy expenditure accurately, it is impossible to accurately estimate calorie intake in real-world environments, as neither individuals nor digital tools can accurately estimate portion sizes (5), and data from food labels and restaurant nutrition listings is frequently inaccurate (6).

The failure of the calorie-centric model is primarily apparent, however, in the continued existence of the obesity epidemic despite widespread private and public investment in increasing the number of calories overweight and obese individuals burn while reducing the number they eat. The authors of this review argue the probability of successfully resolving the obesity epidemic using these same methodologies is virtually zero and that this failure indicates these interventions have failed to target the root cause of the epidemic (7).

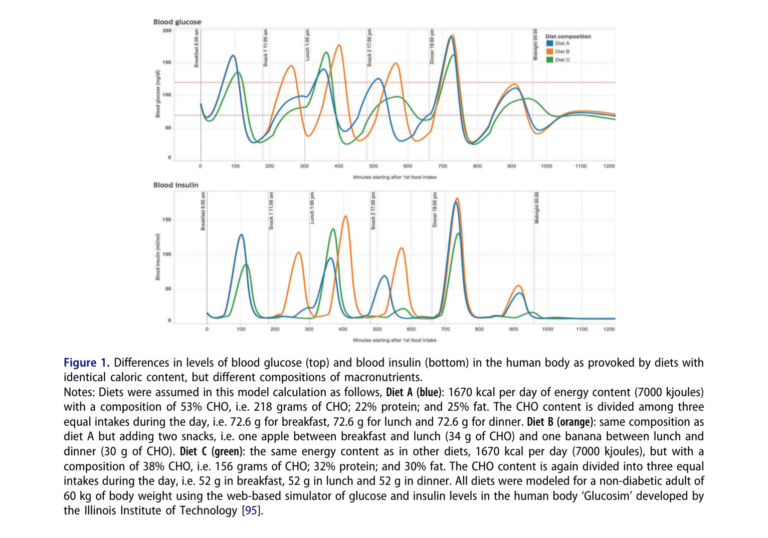

An alternative framework — termed “Concept 2” by the authors — views obesity as a condition related to fat regulation. Fat tissue is primarily regulated by insulin. When insulin levels are high, carbohydrates and fats are shuttled toward storage and accumulation; when insulin levels are low, fatty acids stored in fat tissue are broken down and burned as energy. If insulin remains chronically elevated, the natural cycle of fat storage and release breaks down and fat continually accumulates. Ubiquitous access to and consumption of high-glycemic carbohydrates, which cause high and sustained elevation of insulin levels, would cause just such a breakdown. Figure 1, consistent with Concept 2, illustrates how diets containing an identical number of calories but varying slightly in composition can lead to substantially different serum insulin and glucose profiles over the course of the day.

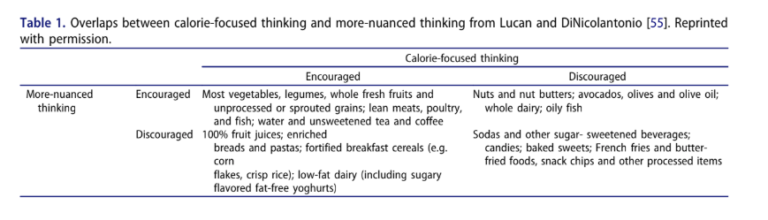

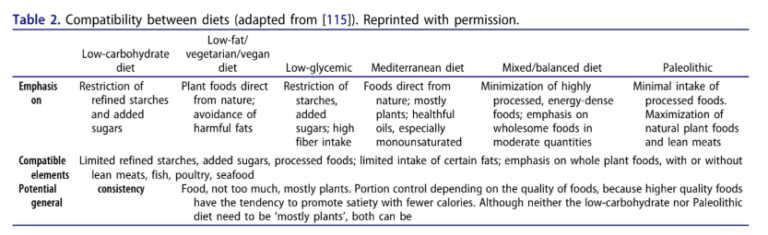

As Tables 1 and 2 show below, Concept 1 and Concept 2 encourage and discourage many of the same foods. Whole fruits, vegetables and lean meats are universally supported while processed sugars and fat- and carbohydrate-laden “junk” foods are universally discouraged. These recommendations are shared by many modern, mainstream dietary recommendations. The Concept 2 framework, however — as well as that of diets aligned with this concept, such as low-carbohydrate, low-glycemic, and to some extent paleolithic diets — specifically suggests refined, non-sugary foods such as breads, cereals, pastas, and low-fat dairy are obesogenic while unrefined fatty foods such as nuts, oils, and whole dairy are not.

The authors note Concept 2 also moves the locus of discussion beyond the simplistic individual understanding (eat less, move more) inherent in Concept 1 to include the public and private entities that have shifted the food environment toward highly accessible, high-glycemic foods. Under the authors’ second framework, these entities bear a greater share of the responsibility, as they have contributed to misinformation and the creation of a food environment that makes it easier to eat an obesogenic diet and more difficult to eat a healthy diet.

Given the apparent failure of Concept 1 to restrain the growth of the obesity epidemic, further exploration of Concept 2 is warranted.

Note these and similar arguments, as well as the differences between these concepts (the latter of which has been referred to as the “alternative hypothesis”) are explored at length in the works of Gary Taubes (8).

Notes

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight; Pathways to Obesity; Widespread misconceptions about obesity

- Energy balance and its components: Implications for body weight regulation; Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on body weight

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Energy balance measurement: When something is not better than nothing; Validity of the remote food photography method for estimating energy and nutrient intake in near real-time; A new method for measuring meal intake in humans via automated wrist motion tracking; Energy intake estimation from counts of chews and swallows

- Differences in the nutritional content of baby and toddler foods with front-of-package nutrition claims issued by manufacturers v governments / health organizations; Measured energy value of pistachios in the human diet; The accuracy of stated energy contents of reduced-energy, commercially prepared foods; The biasing health halos of fast-food restaurant health claims: Lower calorie estimates and higher side-dish consumption intentions

- Trends in adult body mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014; Statistical review of US macronutrient consumption data, 1965 – 2011: Americas have been following dietary guidelines, coincident with the rise in obesity; Why we get fat and what to do about it

- Good Calories, Bad Calories; Why We Get Fat

Is the Calorie Concept a Real Solution to the Obesity Epidemic?