This 2018 review summarizes the clinical evidence supporting the use of a ketogenic diet for Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and provides guidance as to its safe, effective clinical application.

In the late 1800s, before the pathophysiology of diabetes was understood, fasting and/or carbohydrate-restricted diets were known to reverse the symptoms of diabetes. An 1877 textbook noted, “There are few diseases which present to the practitioner so clear an indication of what is to be done … a Diabetic should exclude all saccharine [sugary] and farinaceous [starchy] materials from his diet.”

Drs. Frederick Allen and Elliot Joslin also employed fasting and/or low-carbohydrate diets to treat diabetes in the early 1900s, with the latter allowing unlimited consumption of non-carbohydrate-containing foods.

When insulin was discovered in 1921, recommendations on carbohydrate restriction began to loosen; by 1971, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), without citing any evidence, argued specifically that carbohydrate restriction was no longer necessary (as of 2008, a low-carb diet is one of the dietary patterns recommended by the ADA).

Carbohydrate restriction remains, however, a direct treatment for the pathophysiology of diabetes. Insulin treatment may be harmful to some diabetics, exacerbating an existing state of hyperinsulinemia; carbohydrate restriction, conversely, reduces glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance simultaneously.

The review authors survey a variety of research — ranging from tightly controlled clinical trials to free-living research and clinical anecdotes — that demonstrates ketogenic and carbohydrate-restricted diets can reduce the severity of, or even reverse, diabetes. For example:

- In a small inpatient trial, blood glucose levels dropped substantially enough to significantly reduce HbA1c levels over a mere 14 days.

- In a 16-week trial at the Durham VA Medical Center, seven out of 28 subjects were able to discontinue diabetes medication, and mean HbA1c decreased from 7.4% to 6.3%.

- In a large cohort study, 94% of patients who were on insulin and began a ketogenic diet were able to reduce or eliminate their use of insulin.

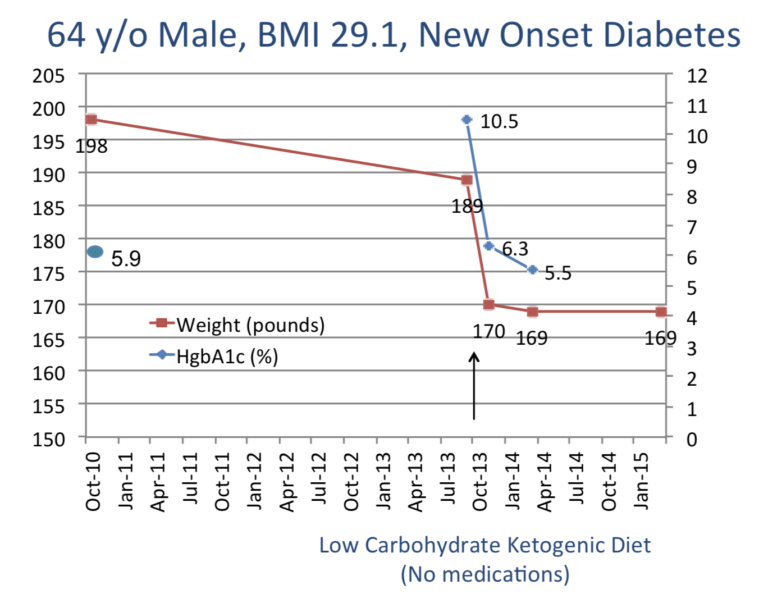

Two of the review authors (Westman and Yancy) treat diabetic patients with a ketogenic diet at a university-based medical clinic. Highlighting the effectiveness of the treatment, they describe a 60-year-old male patient who reduced his HbA1c from 10.5% at baseline to 6.2% within one month and 5.5% within five months. This fits the criteria for complete remission of diabetes and would be considered a cure if maintained through five years (this same subject maintained remission for at least 24 months).

The authors note the primary concern in diabetics following a ketogenic diet is prevention of hypoglycemia, not hyperglycemia. Diabetics beginning a severely carb-restricted diet must regularly check their blood sugar levels and reduce or discontinue insulin and glucose-lowering medications to prevent glucose levels from dropping too low.

Standard-of-care (pharmacological treatment paired with general weight loss instruction) reverses diabetes in fewer than one in 14,000 patients annually; according to the authors of this review, most patients who enter their clinic have been told they have a chronic, progressive condition.

Conversely, a carbohydrate-restricted diet has been demonstrated to mitigate both the acute consequences of diabetes (hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia) and the chronic condition. On a patient level, this supports adherence, as low-carb diets provide patients with the opportunity to reduce their medication dosage over time. On a broader level, this indicates carbohydrate restriction has a significant role to play in reversing the growing social and economic burden of diabetes and the many metabolic conditions tied to it.

Implementing a Low-Carbohydrate, Ketogenic Diet to Manage Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus