The musculature around the hip includes some of the largest and most powerful muscles in the human body. The extension of the hip can move thousands of pounds, propel the body up and over obstacles equal to or greater in height than the body in motion, and move the body at speeds greater than 25 miles per hour. But running, jumping, and lifting are just a few of the hip’s unique abilities. Its structure allows for stability in our standing posture at a low metabolic cost, its radical range of motion allows for mobility in virtually any anatomical plane or axis, and its composite muscles are also capable of providing for ambulation across long distances and for long durations. It is likely the most important target area for trainees and fitness trainers to develop, as the hips play an integral role in daily life, exercise, and physical performance.

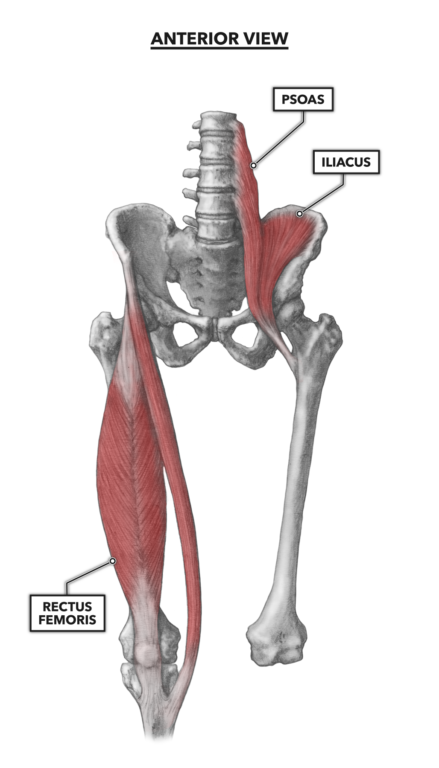

On the anterior of the hip (Figures 1 and 2), one will find muscles primarily involved in flexion.

Superficial Muscles

Rectus femoris – The rectus femoris is located along the anterior surface of the thigh. It has a central line of connective tissue along its length, and its muscle fibers radiate from it in a bipennate manner. The muscle attaches proximally at the anterior iliac spine and near the anterior lip of the acetabulum. For the purpose of hip movement, the attachment to the ilium is important. The muscle crosses the hip joint and knee and attaches distally at the superior border of the patella.

The rectus femoris is the only muscle in the quadriceps muscle group involved in hip flexion, as the other three muscles have proximal attachments on the femur below the hip. The rectus femoris works simultaneously with the iliacus, psoas, and tensor fasciae latae in hip flexion, but one needs to remember the role of gravity in movement as well. When you squat, these muscles do not actively contract to pull the body down; gravity does that. Rather, the rectus femoris and other flexors act eccentrically to control and stabilize the movement.

Sartorius – The sartorius muscle is the longest muscle in the human body, obliquely spanning the distance from its proximal attachment on the anterior superior iliac spine, wrapping around the posterior surface of the medial condyle of the femur, and continuing down to its distal attachment on the anterior medial surface of the tibial head. In the final few inches of the tendon, where it curves to anterior, it merges with the tendons of the gracilis and semitendinosus to form a connective tissue structure referred to as the pes anserinus. The sartorius assists in four different movements: flexion, abduction, and lateral rotation at the hip, then also flexion of the knee. If you pick up your foot, bend your knee, and move the sole of the foot to a position where you can see it, the sartorius will be carrying out all four of its functions.

Deep Muscles

Iliacus – The iliacus is a flat and roughly triangular-shaped muscle. It lies in the concavity of the inner surface of the ilium (the iliac fossa), proximally within the interior of the pelvis, broadly across the ilium, and forward to the anterior inferior iliac spine. It attaches distally on the femur at the lesser trochanter.

The muscle is generally considered an anterior flexor of the hip, particularly when the foot is less stable. However, the iliacus functions as a postural muscle when the feet are planted and the body erect. It completes this function by pulling the top of the pelvis around the axis of the hip. If you are lying with your legs straight and you sit up, the iliacus assists in this motion. If you bend your knees while lying down, you have pre-shortened the iliacus, and it can no longer contribute to sitting up. The iliacus can also contribute to rotation of the femur.

Psoas – The psoas is another deep muscle in close proximity to the iliacus. Together, these muscles are frequently referred to as the iliopsoas, though they are indeed separate muscles. In fact, in about half the population, there is a psoas major and a psoas minor. The psoas attaches proximally along the transverse processes and bodies of the lumbar vertebrae. It attaches distally, along with the iliacus, to the lesser trochanter of the femur.

The muscle can be used as a postural muscle to maintain the lordotic arch if the pelvis or feet are stabilized. If the feet are not stable, the psoas becomes an anterior hip flexor. Again, as with the iliacus, if you are lying with your legs straight and you sit up, the psoas assists in the movement. If you bend your knees while lying down, you have pre-shortened the psoas, and it can no longer contribute to sitting up.

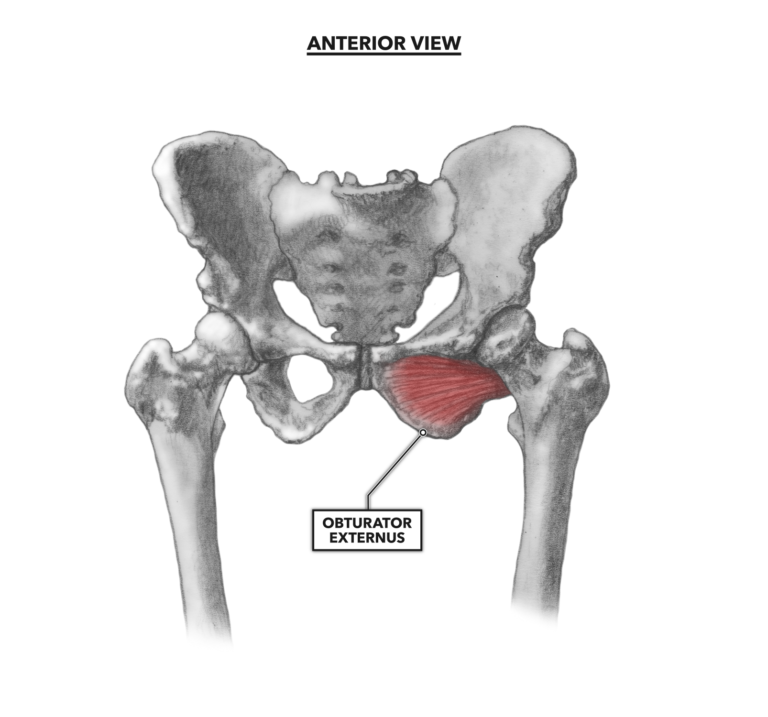

Obturator externus (Figure 2) – This is a small, deep muscle that attaches proximally to the anterior pubis and ischium. It then runs slightly to the posterior and around the rear of the femur, where it attaches distally to the femoral neck in a fossa separating the femoral head and the greater and lesser trochanters. The external obturator is a lateral rotator (involved in external rotation) of the femur, but it functions primarily in keeping the head of the femur firmly seated in the acetabulum. During hip flexion, the muscle also stabilizes the joint as a postural muscle, maintaining an internal-external angle throughout the range of motion.

To learn more about human movement and the CrossFit methodology, visit CrossFit Training.