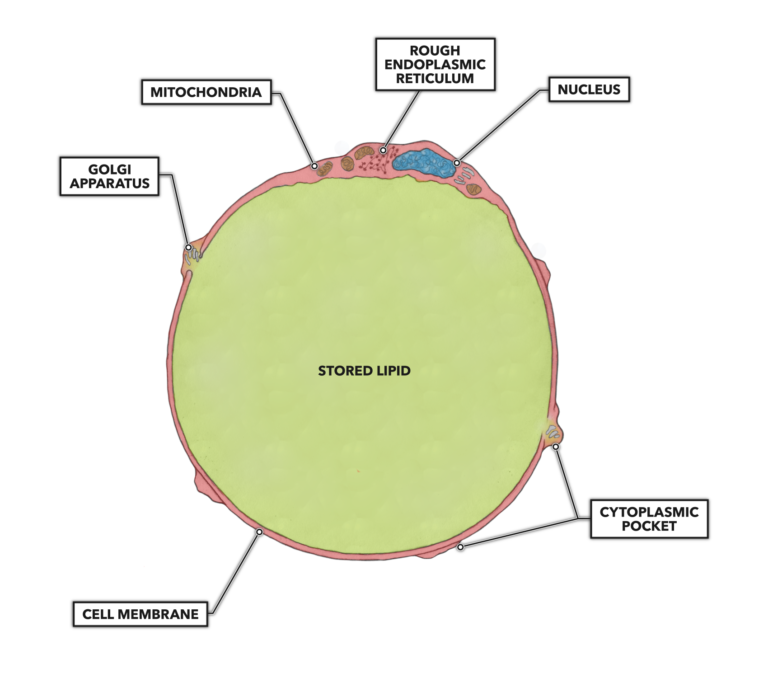

Fat cells, also known as monovacuolar cells or adipocytes, are essentially large lipid droplets surrounded by a thin cell layer. The cells are mononucleate, with the nucleus found on the periphery of the cell, bundled with other organelles in the largest accumulation of cytoplasm. The remainder of the cytoplasm is spread thinly around the adipocyte cell boundary. This provides an appearance of a cell membrane stretched around the lipid with pockets of cytoplasm appearing randomly on the surface. The lipids stored inside those cells are primarily triglycerides (three fatty acids bound to a glycerol backbone).

Figure 1: Adipocyte structure

Humans have a large range of cell sizes. Although the average size is frequently reported to be 0.1 millimeters (100 μm), data indicates a much more varied norm, with individuals exhibiting an average cell size of 70 μm and a peak cell size of 110 μm (1). But these dimensions can be much smaller or tremendously larger depending on the nutritional state of the individual. Obese individuals will tend to have larger, hypertrophied fat cells compared to slimmer people.

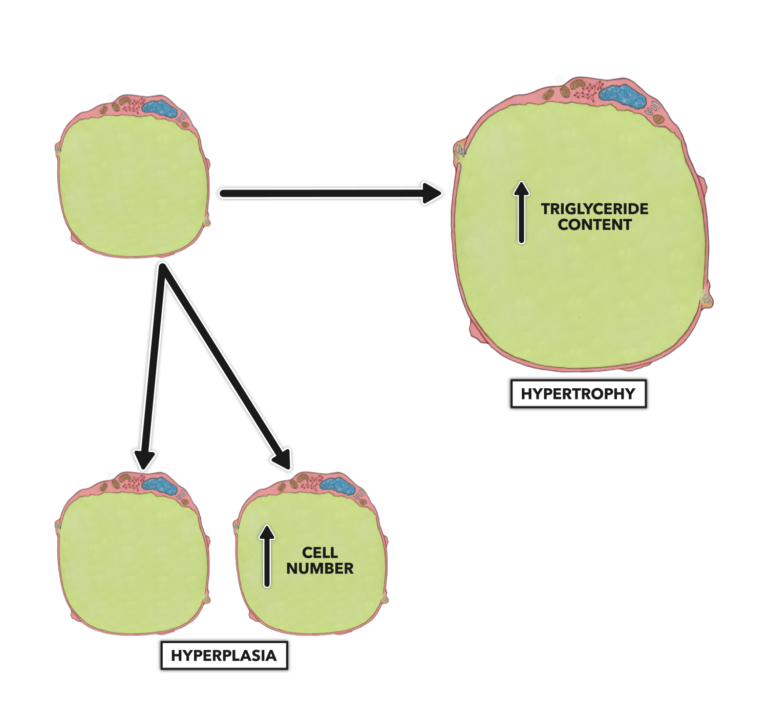

Fat cells and fat tissue are adaptive entities that can be affected by nutritional habits and exercise. The cells can adapt to store more energy by simply adding more fat to their contents (hypertrophy of fat cells), but there is a critical volume when additional mass cannot be added to individual cells. When about four or more times the normal content of fat is present, it is thought that a size limit is reached and the adipocyte will become mitotically active and begin cell division (hyperplasia of fat cells) to open up new lipid storage space.

Figure 2: Hyperplasia of fat cells

This latter process, fat cell hyperplasia, occurs in extreme obesity, and most of us are not in danger of adding new fat cells. What we are in danger of is adding new triglycerides to the interior of our existing adipocytes simply by eating a caloric excess, consuming an inappropriate nutritional composition, or by underexerting ourselves and burning too few calories.

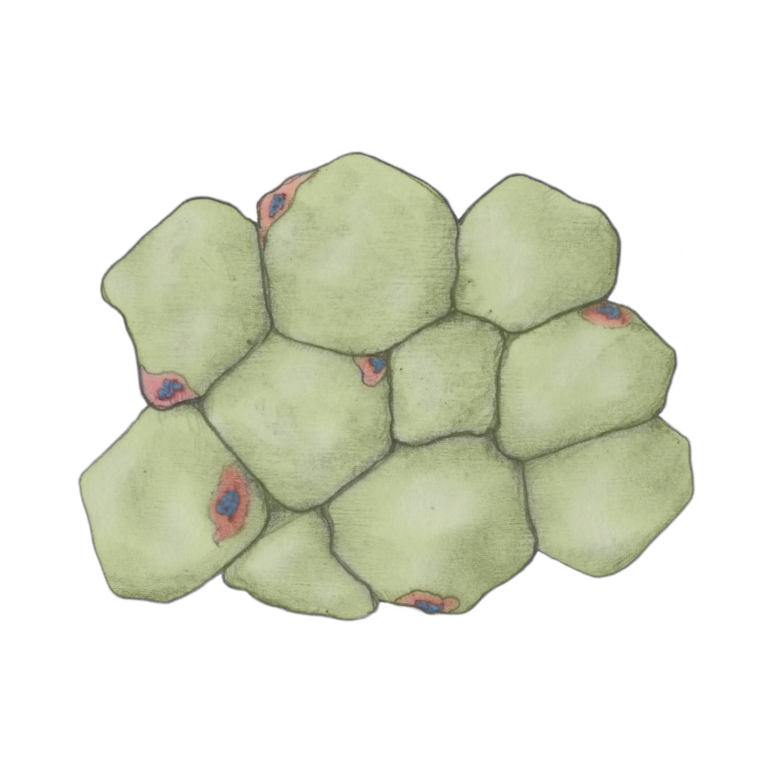

In isolation, an adipocyte assumes a spheroid shape, but when collated into fatty tissue, the cells are shaped by pressures from adjacent cells and tissues. If you look at fat cells under a microscope, you will note they look reminiscent of the arrangement of styrofoam beads in the wall of a cooler or like an assembled mass of polyhedral dice.

Figure 3: Collated fat cells in fat tissue

In infants and to a much lesser extent in adults, there is a second type of fat tissue called brown fat. Composed of a subtype of adipocytes that are more metabolically active than white fat, brown fat produces heat that helps keep infants warm. These cells are multinucleate and have more cytoplasm, more bioenergetic organelles, and less fat content than white fat cells. In adults, brown fat is largely absent, found in exceedingly small amounts in the neck and shoulders in some humans.

Although adipocytes comprise the major mass of cells present in adipose tissue, fibroblasts, macrophages (leukocyte found in tissue not blood), and endothelial cells are also present as part of the structural unit. As one would expect, there are quite a few blood vessels perfusing fat tissue. This facilitates lipid deposition (adding fat contents to an adipocyte) and lipid mobilization (removing fat from an adipocyte).

Additional Reading

References

- McLaughlin T, et al. Subcutaneous adipose cell size and distribution: Relationship to insulin resistance and body fat. Obesity, 22.3(2014): 673–680. 2014.

To learn more about human movement and the CrossFit methodology, visit CrossFit Training.