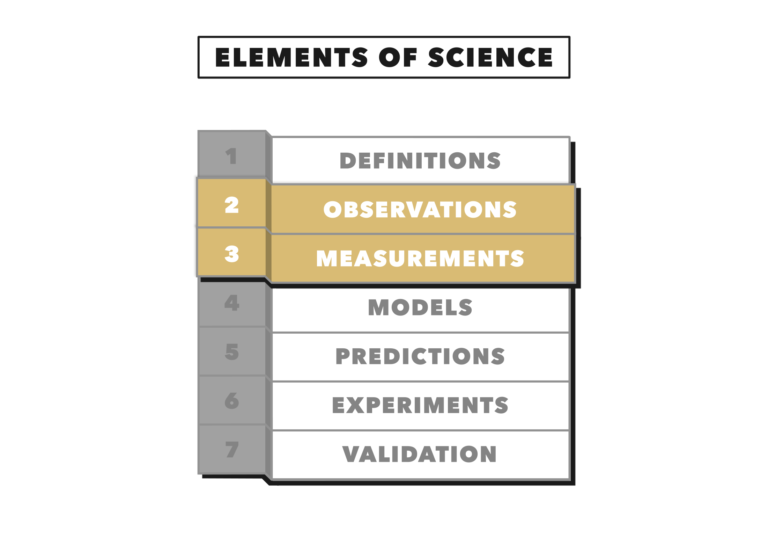

As we move through a linear consideration of the elements of science, we arrive next at observations and measurements.

We can recall that observations, as defined in our science glossary, are registrations of the real world on a sense or sensing instrument. Measurements are captures of these real-world observations on a standard scale. From these definitions, we can arrive at facts: observations measured against a standard.

We also recall that a goal of science is to move from the subjective to the objective. It is with that goal in mind that we consider the relationship between observations, measurements, and facts.

Consistency and Objectivity

Science deals with observations of the real world — obtained via the use of our senses — which we can define, record, measure, and quantify or order. Record means to capture data in a physical medium that is amenable to measurements and does not simply refer to the notes of an observer.

In order to be useful, each model of a real-world phenomenon must be consistent for all observers. From the imperative demand for consistency, then, comes the requirement for measurements. Measurements compare observations with standards, creating what science calls facts. In this context, the terms “measurements” and “facts” become interchangeable. They are what scientists and philosophers call a posteriori, meaning “after the fact” or “from experience.” Making measurements, showing consistency, and sharing results are all scientific processes that assure objectivity. Science thus becomes the objective branch of human knowledge.

Put another way, the act of measuring, the grading of observations according to standards, and the use of precision in language are processes necessary to achieving objectivity: the separation of observations from perception processes.

Accuracy and Repeatability

Scientists must grapple with the fact that all measurements are eventually sensed and perceived by a human. We use our eyes to read a ruler. Science is based on a comparison with the ruler, subject to our errors in reading it. (Measurement training helps us develop a perspective of how brief and limited human observations are, and how an accuracy limitation underlies each measurement.)

The scientific community thus automatically subjects any novel facts to tests for repeatability. Science measures repeatability statistically in terms of variability or accuracy. The process of reducing an observation to a measurement is not complete until an assessment of its accuracy is available.

In conclusion: Observations are too general and include subjective perceptions. The first step in objectivity is to compare the observations to standards. In the most general sense, this is the process of making measurements, or creating facts. Science looks for repeatable things called patterns in the measurements. The descriptions of the patterns are models, as we will consider in our next entry in this series.

Additional Reading

Comments on Elements of Science: Observations & Measurements

An observation is a registration of the real world on a sense or sensing equipment. The capture of observations on a standard scale is measurement, and in the singular instance creates a fact. Mapping a fact to a future fact is a forecast of a measurement constituting a prediction – an unmaterialized effect.

A representation of a real world cause and effect relationship expressed in natural language, logic, or mathematics is a model. There are four grades, or qualities, of model – conjectures, hypothesis, theories, and laws.

A conjecture is a consistent cause and effect relationship, such as a ranking or heritage, direct or by analogy to another domain. A hypothesis is a conjecture based on all existing data in its domain making a non-trivial prediction. A theory is a hypothesis making a significant, i.e., non-trivial, validated prediction. A law is a theory for which all explicit and implicit predictions have been validated.

Science discovers facts and not models. Models are the containers of science. The power in science is valid prediction. A theory finds validation from the empirical evidence and statistics for it having better-than-chance predictive value.

Yes! Looking forward to reading the rest in this series! Thank you

Elements of Science: Observations & Measurements

2