In this 2015 review, a team comprising Richard Feinman, Eugene Fine, Eric Westman, and others summarizes the evidence supporting carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in the treatment and management of Type 2 diabetes.

The authors provide the following definitions for different calorically restricted diets:

- Very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet (VLCKD): 20-50 g/d of carbohydrate

- Low-carbohydrate diet: <130 g/d or <26% of calories from carbs

- Moderate-carbohydrate diet: 26%-45% of calories from carbs

- High-carbohydrate diet: >45% of calories from carbs

For context, the authors note that the average American diet is estimated to be 49% carbohydrate, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend a 45-65% carbohydrate diet, and the American Diabetes Association recommends, by the authors’ definition, a high-carbohydrate diet for diabetics.

They summarize the evidence in 12 points as follows:

- Hyperglycemia is the most salient feature of diabetes. Dietary carbohydrate restriction has the greatest effect on decreasing blood glucose levels.

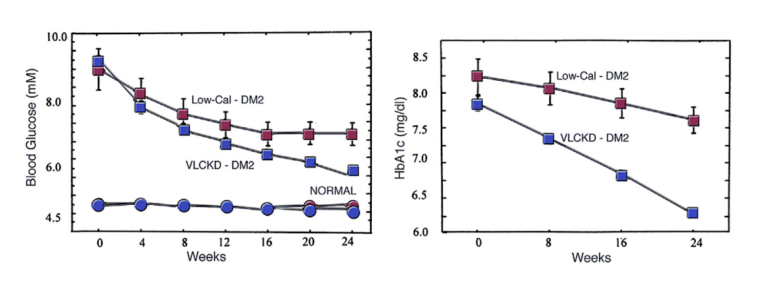

The most characteristic feature of diabetes (both Type 1 and Type 2) is an excessive glucose response to food; other effects, such as impacts on insulin, are downstream of this primary defect. It is uncontroversial that dietary carbohydrate intake is the main determinant of blood glucose levels. A 2012 trial showed that a very low-calorie ketogenic diet led to greater suppression of fasting glucose and HbA1c than caloric restriction over 24 weeks. (Figure 1)

- During the obesity and Type 2 diabetes epidemics, caloric increases have been due almost entirely to increased carbohydrate intake.

Between 1971 and 2000, the observed increase in the average American’s caloric intake (6.8% in men, 21.7% in women) was almost entirely accounted for by an increase in carbohydrate consumption, which increased 23.4% in men and 38.4% in women. Mechanistically, the sustained hyperinsulinemia consequent to chronic carbohydrate overconsumption increases liver fat and hepatic insulin resistance, which then leads to increased fasting glucose, increased fat storage in other tissues, and impaired pancreatic beta-cell function. - Benefits of carbohydrate restriction do not require weight loss.

A 2010 trial showed that a diet that moderately reduced carbohydrate intake to 30% improved glycemic control even in the absence of weight loss. Thus, while carbohydrate restriction can be an important tool to induce weight loss, a low-carb diet does not need to result in weight loss to improve blood glucose control. - Although weight loss is not required for benefit, no dietary intervention is better than carbohydrate restriction for weight loss.

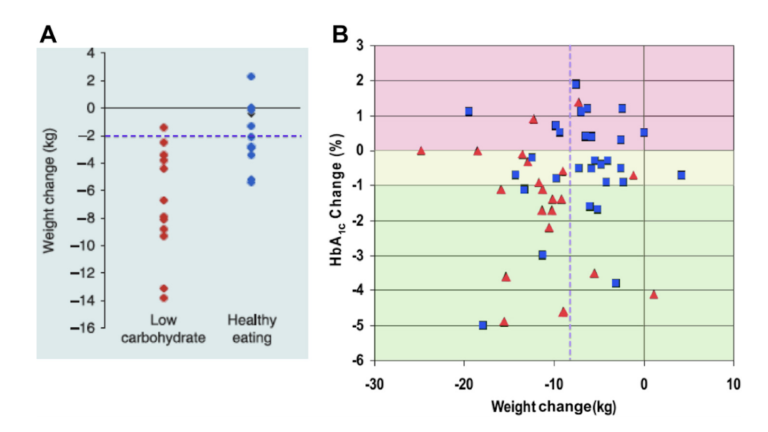

Two recent trials (Figure 4) randomized diabetic subjects to a low-carbohydrate or low-fat diet. In both cases, carbohydrate restriction led to more consistent weight loss. This is particularly important given the ineffectiveness of low-fat diets in inducing weight loss, as is shown in the Women’s Health Initiative and elsewhere. Additionally, most popular low-carb diets are delivered ad libitum, and induce weight loss without any deliberate caloric restriction.

Figure 4: Effect of diet on weight loss in people with type 2 diabetes. (A) Data from Dyson et al. [23] comparing a low-carbohydrate diet with the “healthy-eating diet” of the Diabetes UK agency. (B) Comparison of weight loss and changes in glycated hemoglobin. Very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet (red triangles) is compared with a low-glycemic index diet (blue squares). Data from [6].

- Adherence to low-carbohydrate diets in people with Type 2 diabetes is at least as good as adherence to any other dietary interventions and is frequently significantly better.

In 19 clinical trials, similar adherence rates were shown for low-carb and low-fat diets. Widespread anecdotal evidence, collected in the Active Low-Carber Forum, suggests low-carbohydrate diets induce more consistent satiety and reduce hunger, improving ease of compliance. - Replacement of carbohydrate with protein is generally beneficial.

Most low-carb diets replace carbohydrate with fat. However, those studies that analyze the impact of high-protein, low-carb diets have been associated with greater weight loss and greater preservation of fat-free mass than higher-carb diets. - Dietary total and saturated fat do not correlate with risk for cardiovascular disease.

A large volume of literature has documented the failure of the diet-heart hypothesis, which links saturated fat consumption to heart disease risk. Recent meta-analyses have reinforced this observation, demonstrating that if there are any cardiovascular benefits associated with a reduction in saturated fat (and there may not be), they are very small. - Plasma saturated fatty acids are controlled by dietary carbohydrate more than by dietary lipids.

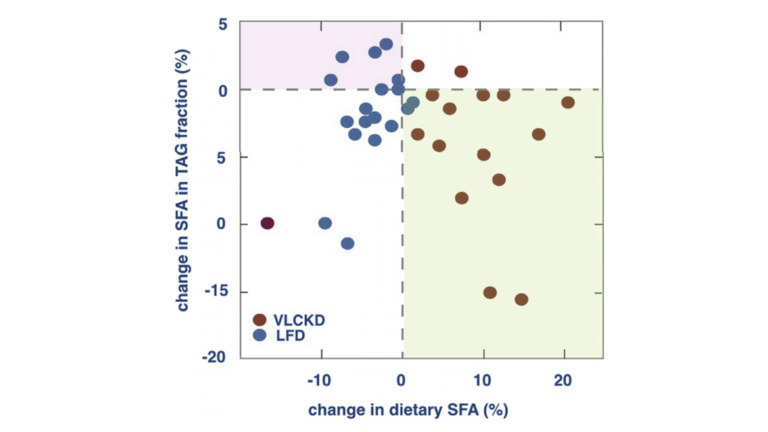

While dietary saturated fats are not correlated with heart disease, plasma saturated fats are. Increased plasma saturated fats, however, are associated with increased net triglyceride production, which is itself associated with increased carbohydrate, not saturated fat, consumption. (Figure 7)

Figure 7: Lack of association between dietary and plasma TG SFAs. In the green area, an increase in dietary SFA is associated with a reduction in SFA in the TG fraction in plasma. In the pink area, SFA increases even though dietary SFA is reduced. Data from [61]. LFD, low-fat diet; SFA, saturated fatty acid; TG, triglyceride; VLCKD, very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet.

- The best predictor of microvascular and, to a lesser extent, macrovascular complications in patients with Type 2 diabetes is glycemic control (HbA1c).

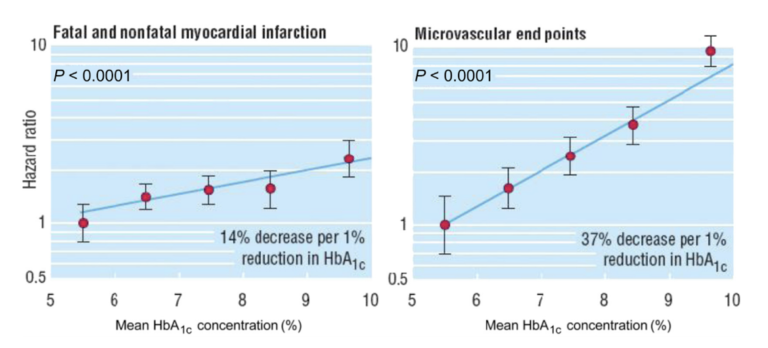

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) found there was a 14% decrease in myocardial infarction and a 37% decrease in microvascular endpoints for every 1% reduction in HbA1c. These findings suggest HbA1c is in itself a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes in diabetics. (Figure 8)

Figure 8: Dependence of risk for myocardial infarction and microvascular end points on hemoglobin A1c. Data adjusted for age at diagnosis of diabetes, sex, ethnic group, smoking, presence of albuminuria, systolic blood pressure, high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides. Modified from [65], [66], [67]. Used with permission. Hemoglobin (Hb).

- Dietary carbohydrate restriction is the most effective method (other than starvation) of reducing serum TGs and increasing high-density lipoprotein.

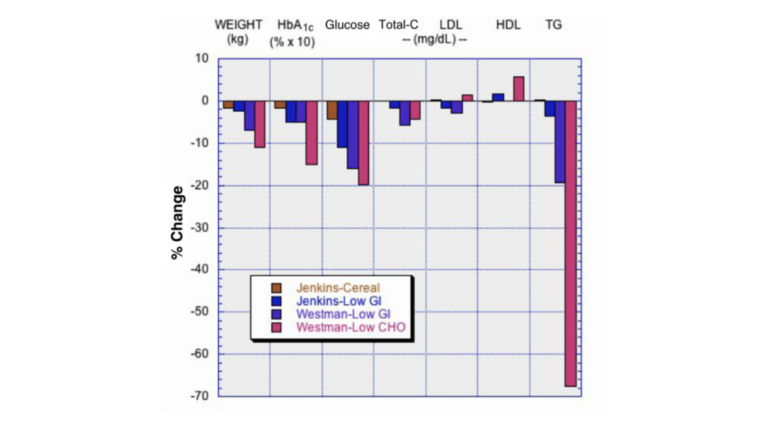

In two simultaneous studies, high-carbohydrate, low-glycemic-index, and low-carbohydrate diets were tested in diabetics. The low-carbohydrate diet led to the greatest decrease in weight, HbA1c, and glucose, as well as the greatest increase in HDL and greatest decrease in triglycerides. While this group saw an increase in LDL cholesterol, newer markers, such as apoB, the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL, and the ratio of triglycerides to HDL, have been shown to better predict heart disease risk; these newer markers are more reliably improved by carbohydrate restriction. (Figure 9)

Figure 9: Comparison of low-glycemic index diet with high-cereal diet, and of low-glycemic index diet with low-carbohydrate diet. Data from [6], [70]. Redrawn from [75]. CHO, carbohydrate; GI, glycemic index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglyceride; Total-C, total cholesterol.

- Patients with Type 2 diabetes on carbohydrate-restricted diets reduce and frequently eliminate medication. People with Type 1 usually require lower insulin.

Multiple recent studies have shown that Type 2 diabetic patients frequently are able to reduce or eliminate medication in the context of a very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet. - Intensive glucose lowering by dietary carbohydrate restriction has no side effects comparable to the effects of intensive pharmacologic treatment.

Several medications used to pharmacologically lower blood glucose in diabetics have side effects, such as potentially increasing the risk of heart disease associated with rosiglitazone. Glucose lowering through diet is less likely to have these or other side effects.

Existing efforts have failed to halt the obesity epidemic, and the benefits of carbohydrate restriction have become well-documented. In light of these facts, the authors argue that the use of carbohydrate restriction for the treatment of diabetes should be debated more seriously.