This 2016 review summarizes various pathways by which IGF and insulin suppression may slow or inhibit tumor growth.

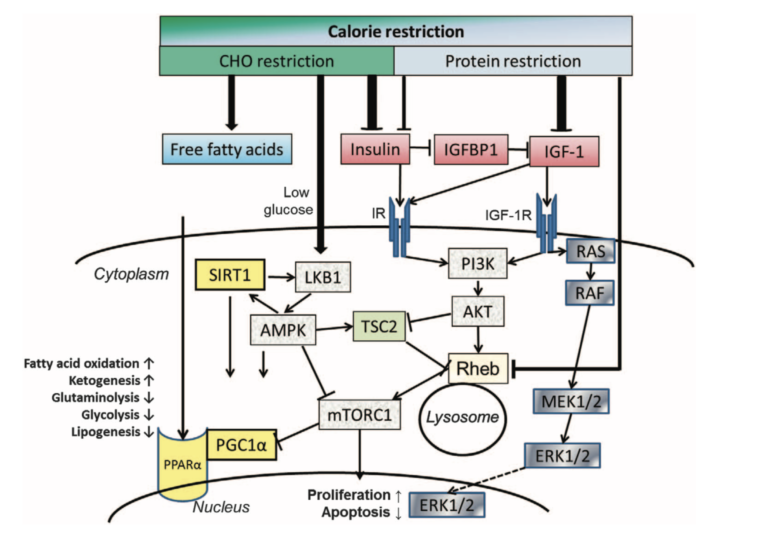

Multiple pathways related to insulin and IGF may play roles in tumor suppression. Both insulin and IGF-1 are growth-stimulating and anabolic hormones, and insulin and IGF receptor activation upregulates pathways central to carcinogenesis (see Figure 2). Many of these effects are tied to the PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 pathway, the upregulation of which is linked to tumor growth and progression. High glucose levels may independently promote tumor growth due to the dependence of tumor cells on high glucose uptake, though some rat studies have suggested elevated IGF-1 levels reverse the growth-inhibiting effects of lowered glucose levels. These effects are most pronounced within insulin-sensitive tumors, which include breast and colon cancers.

Insulin/IGF receptor binding. As tyrosine kinase receptors, the IR and the IGF receptors, consist of an extracellular ligand-binding domain and a cytosolic tyrosine kinase domain that autophosphorylates upon ligand binding and transphosphorylates several substrates that initiate downstream signaling. The IR shares ~50 and 80% homology with the ligand-binding and tyrosine kinase domain, respectively, of the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R). It exists in two isoforms, IR-A and IR-B, which promote either mainly mitogenic or metabolic effects, depending on the ligand and the cellular context, allowing cells flexibility in responding to mainly one or the other stimulus. In general, IR-A is preferentially associated with mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signaling, whereas IR-B is associated with cell differentiation and metabolic effects. A predominant expression of IR-A has correspondingly been found in fetal tissue and tumors with autocrine production of IGF-2, which binds this receptor with 30–40% affinity compared with insulin. In this way, these tumors promote cell proliferation in an autocrine manner. IGF-2 also binds to the IGF-1R, whereas IGF-1 binds to its own IGF-1R and to hybrid receptors of IGF-1R and IR-A as well as IGF-1R and IR-B. Physiological concentrations of insulin show no measurable binding to the IGF-1R both in vitro and in vivo. Nevertheless, in mammals, insulin may be the major controller of insulin/IGF-1 action due to its effect on the bioavailability of IGF-1.

While carbohydrate restriction (including through a ketogenic diet) has been shown to lower both insulin and glucose levels, both rodent and human studies have shown that fasting has a greater effect on IGF-1 suppression — and in humans, specifically when fasting includes protein restriction. Rodent studies have consistently shown that various forms of caloric restriction inhibit tumor growth and/or prevent tumor development or metastasis, and a handful of preclinical studies show direct benefits from carbohydrate-restricted (but not calorie-restricted) diets. Human evidence, however, remains preliminary and is primarily limited to small pilot studies and case reports.

Notably, the effects seen in rodents may not extrapolate directly to humans. Insulin and glucose kinetics in rodents and humans differ significantly, and rodents are able to tolerate a degree of fasting-related weight loss (up to 50% of baseline body weight) that would be harmful to humans. Future research will need to better understand the dose-response relationship between various forms of dietary restriction and insulin and/or IGF-1 suppression in humans to develop dietary restriction regimens that suppress cancer growth without harmful side effects. The authors note the use of specific glucose- and/or insulin-suppressing drugs, independently or alongside dietary restriction, may help to safely moderate hormonal responses.

Overall, the authors find compelling mechanistic evidence that insulin and IGF-1 suppression may have anti-cancer effects. They also find substantial evidence that diets that reduce insulin and IGF-1 levels reduce tumor progression in rats; human evidence, however, is preliminary and must be gathered cautiously given the known harms of weight loss and cachexia in humans.