The brain is exceptionally sensitive to metabolic disruption (1). Diabetes, insulin resistance, and other forms of metabolic impairment have been linked to cognitive deficits and dysfunction in the U.S., U.K., and Israel (2). As insulin resistance develops, it impairs blood flow throughout the brain via multiple mechanisms, including increased inflammation and decreased nitric oxide (3). The brain is also rich in insulin receptors, and impairments in glucose metabolism and/or insulin signaling may play a direct role in the development of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia; impaired glucose intake is seen in the brains of individuals who will develop dementia before other symptoms are present (4).

The brain maintains its ability to metabolize ketones even when glucose metabolism is impaired. This has led to increasing interest in the use of ketone bodies (and similar tools like a ketogenic diet) to prevent or reverse cognitive decline (5).

This paper outlines two trials and one case study that aim to assess the impact of elevated blood ketones, specifically on measures of cognitive function.

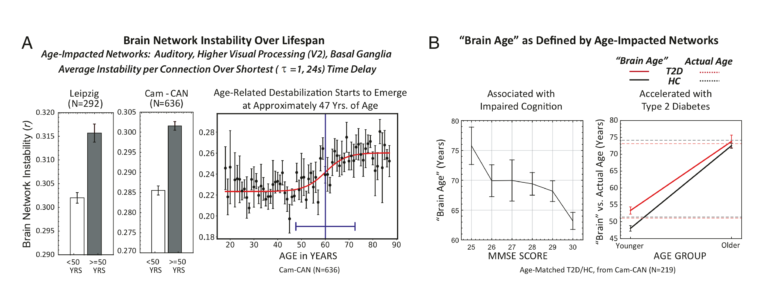

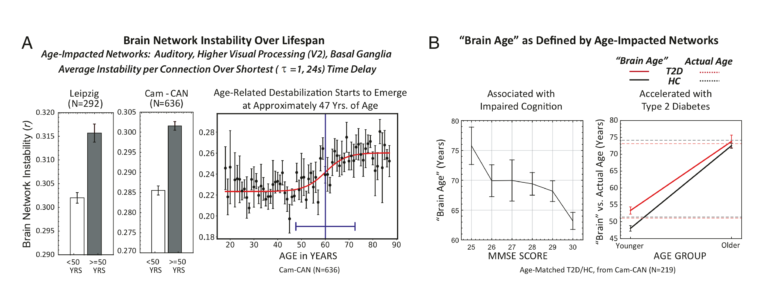

First, the researchers attempted to map the normal time course of aging. Drawing from preexisting MRI data, researchers calculated the average brain network stability, defined as the brain’s ability to sustain coordinated cross-region communication while in the resting state, of individuals at different ages. The results are summarized in Figure 1 below. Brain network stability begins to decline around age 47, after which it follows a sigmoidal function with the rate of decline greatest around age 60. Impaired brain network stability — which, per this methodology, indicates an older “brain age” — was associated with impaired cognition.

Figure 1: Brain network stability followed a sigmoidal function, declining between the mid-40s and mid-70s. Impaired brain network stability was associated with impaired cognitive function. Diabetes accelerated brain aging.

Notably, diabetes increased brain age in younger individuals, with young diabetics showing levels of brain network stability equivalent to that of healthy individuals five years their senior. In older individuals, this effect disappeared.

The researchers then tested the effect of elevated blood ketone levels on network stability. The three tests are outlined below. All three tests used a within-subjects design; that is, each subject was tested in each scenario, with their performance compared across experimental conditions. All subjects were healthy and young (mean age = 28-29).

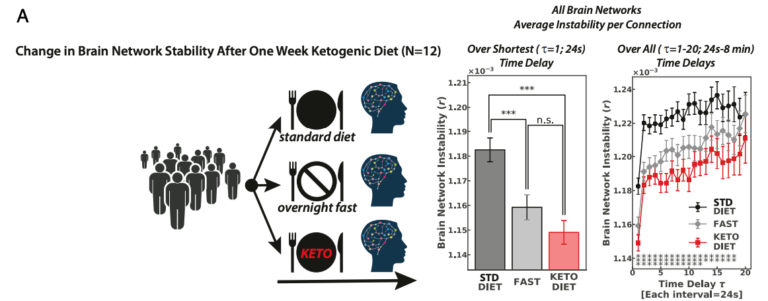

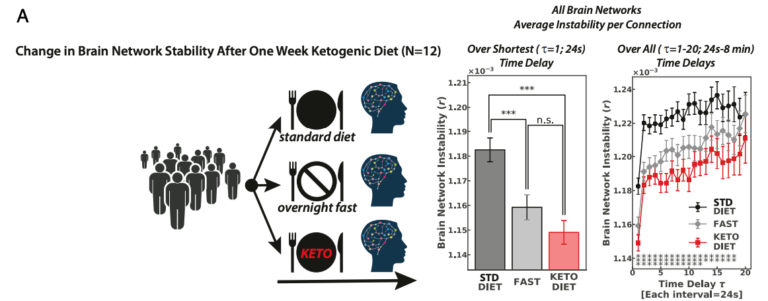

In the first test, subjects were told to maintain a “standard” (habitual) moderate or high-carb diet, or switch to a ketogenic diet. Standard-diet subjects were assessed either without fasting or after an overnight fast. In this test, both overnight fasting and the ketogenic diet led to significant improvements in brain network stability compared to a standard diet without fasting; the differences between an overnight fast and ketogenic diet were not significant.

Experiment 1: Subjects maintained a standard diet, with or without an overnight fast, or a ketogenic diet before being assessed for brain network stability.

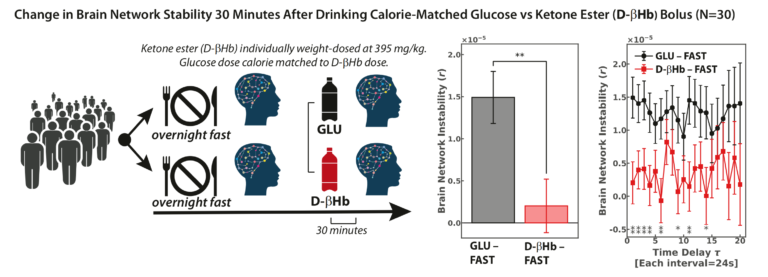

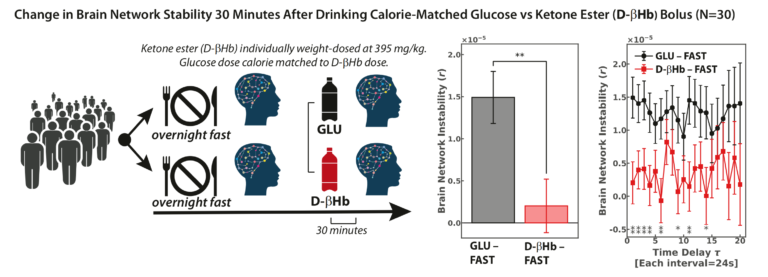

In the second test, all subjects followed a standard diet and fasted overnight. Thirty minutes before brain network stability was assessed, they were given a dose of either glucose or exogenous ketones. In this case, the ketones significantly improved brain network stability. Notably, the glucose beverage led to poorer brain network stability, and the ketone drink led to greater brain network stability.

Experiment 2: Subjects maintained a standard diet, with brain network stability assessed 30 minutes after ingesting either a glucose-rich or ketone-rich beverage.

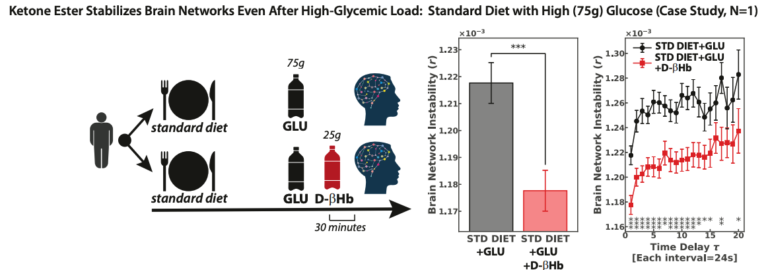

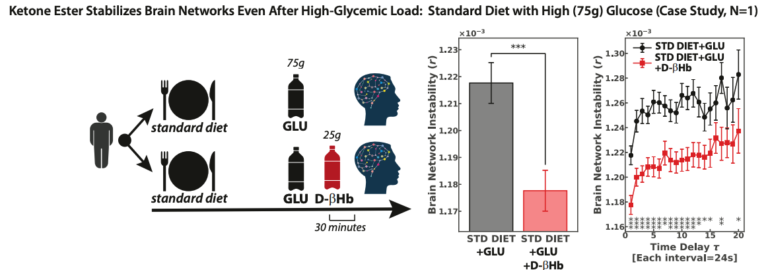

Finally, in the third test, a single subject was maintained on a standard diet without an overnight fast and given either a dose of glucose alone or a dose of both glucose and ketone bodies 30 minutes before brain network stability was assessed. Here again, ingestion of ketone bodies led to significantly improved brain network stability.

Experiment 3: A single subject was given either glucose alone or glucose alongside exogenous ketones to test the effect of ketone elevation even in the context of a high glycemic load.

Taken together, these experiments indicate elevated blood ketone levels — as present after an overnight fast, on a ketogenic diet, or after drinking exogenous ketones — improve brain network stability, even when blood glucose levels are elevated through glucose coingestion. The researchers argued this suggests elevated ketone levels lead to improvements in network stability. It is notable, however, that glucose ingestion acutely impaired network stability even more than a standard, moderate- or high-carb diet, which suggests elevated glucose levels may also impair network stability.

The researchers note the brain primarily relies on glycogen stored in the glia (a smaller glycogen store) as a source of glucose rather than the liver or muscle; as a result, a 12-hour overnight fast may be sufficient in insulin-sensitive individuals to transition the brain to using ketones as a primary fuel. Notably, this may not be the case in insulin-resistant and/or hyperinsulinemic individuals in whom chronically elevated insulin levels suppress ketone production. This suggests insulin resistance may impair cognitive function by diminishing the effect of circadian fasting (6).

Overall, this study illustrates two important points. First, it illustrates the normal time course of brain aging while also indicating diabetes accelerates brain aging in younger individuals. Second, it indicates that even in healthy, young subjects, elevated blood ketone levels improve brain network stability and so would be expected to improve cognitive function. These effects are independent of any impact chronically high or low levels of blood glucose may have on cognitive deterioration over time. These results further support a close link between mental and metabolic health and the importance of continued exploration of metabolic therapies to improve mental health and prevent mental decline.