In the generally accepted model for diabetes, excess calorie consumption leads to obesity, which then causes insulin resistance. This, in turn, causes Type 2 diabetes. The simple causal model is as follows:

Excess energy consumption → obesity → insulin resistance → raised insulin levels → IGT early (pre-diabetes) → IFG (pre-diabetes) → Type 2 diabetes

However, although it is true that Type 2 diabetes is far more common in obese individuals, this does not mean that obesity is a cause of Type 2 diabetes. Correlation does not mean causation.

For example, as discussed in a previous article, individuals with congenital generalized lipodystrophy (GCL) all develop Type 2 diabetes. This occurs despite a complete lack of adipose tissue. Equally, many obese people do not demonstrate any insulin resistance.

In most populations, insulin resistance ± raised insulin levels can be measured many years before any weight gain or a measurable increase in blood glucose level becomes manifest.

All of this means raised insulin levels are most likely an important cause of obesity/Type 2 diabetes rather than the other way around. The obesity that results in susceptible individuals worsens the underlying insulin resistance, thereby leading to frank Type 2 diabetes.

This alternative model in turn suggests the hormone insulin is itself obesogenic, which means that if we can reduce insulin levels, this will, in turn, aid weight loss and may reverse Type 2 diabetes.

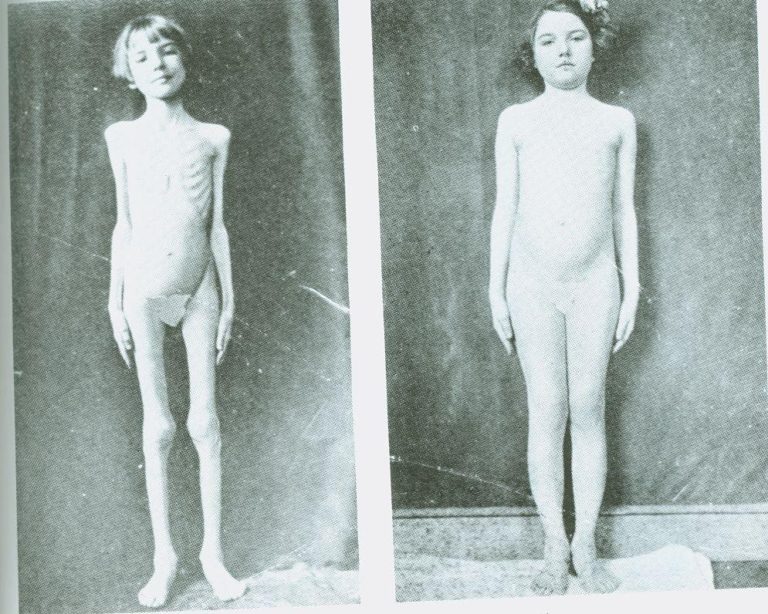

A striking example of the obesogenic nature of insulin can be seen in the era before insulin was isolated and became available as a treatment for Type 1 diabetes. Below are two pictures of a single child, separated in time by a few months.

On the left is how this girl appeared while suffering from Type 1 diabetes with no insulin yet available. On the right is the same child, a few months later, having been given insulin to “treat” her Type 1 diabetes.

The reason for her pre-treatment cachexia is that, without insulin, all energy stores — glucose/glycogen, fatty acids, and protein/amino acids — are released into the bloodstream. This results in rapid and extreme weight loss. With this girl, once insulin was reintroduced, it became possible for the body to store energy again, primarily as adipose tissue, although muscle mass also would have increased.

For various reasons, the energy storage actions of insulin have tended to be relegated to a specific corner in mainstream thinking. The primary focus on insulin, since its isolation and manufacture, has been on its role in lowering blood glucose levels. Due to its life-saving impact in Type 1 diabetes, insulin has been viewed as an almost entirely benign substance.

However, it is clear that insulin is primarily an energy storage hormone, and thus, it promotes weight gain:

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) showed that the average person with Type 2 diabetes gained about nine pounds in their first three years of insulin use. (1)

A high first-phase insulin response to intravenous glucose is a risk factor for long-term weight gain, and this effect is particularly manifested in insulin-sensitive individuals. (2)

The evidence also suggests insulin may have damaging effects:

Although several old studies provided conflicting results, the majority of large observational studies show strong dose-dependent associations for injected insulin with increased CV risk and worsened mortality. Insulin clearly causes weight gain, recurrent hypoglycemia, and other potential adverse effects, including iatrogenic hyperinsulinemia. This over-insulinization with use of injected insulin predisposes to inflammation, atherosclerosis, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure (HF), and arrhythmias. (3, my emphasis)

This is possibly why the ACCORD study, which looked at intensive blood glucose control (referred to as “intensive glycemic strategy” in the study) found, “The intensive glycemic strategy led to an unanticipated excess of total mortality and CVD deaths” (4, my emphasis).

While it is clear that insulin is an essential hormone, excess insulin can also cause both increased weight gain and other significant health problems. Therefore, if we are trying to lower blood glucose levels, it is important to try and avoid raising insulin levels at the same time.

However, most drugs used to lower the blood sugar raise insulin at the same time. Metformin is an agent that can lower insulin resistance, blood glucose levels, and insulin levels simultaneously. It acts in a number of different ways:

Experimental studies show that metformin-mediated improvements in insulin sensitivity may be associated with several mechanisms, including increased insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity, enhanced glycogen synthesis, and an increase in the recruitment and activity of GLUT4 glucose transporters. In adipose tissue, metformin promotes the re-esterification of free fatty acids and inhibits lipolysis, which may indirectly improve insulin sensitivity through reduced lipotoxicity. (5)

Thus, if metformin is given to overweight individuals with insulin resistance, this results in weight loss. A study examining the effectiveness of metformin for obese, nondiabetic individuals found:

The mean weight loss in the metformin treated group was 5.8±7.0 kg (5.6±6.5%). Untreated controls gained 0.8±3.5 kg (0.8±3.7%) on average. Patients with severe insulin resistance lost significantly more weight as compared to insulin sensitive patients. The percentage of weight loss was independent of age, sex or BMI. (6)

However, rather than relying on medications, it is better to look at alternative ways to reduce insulin levels. Perhaps the most effective is exercise, which has been found to consistently reduce insulin resistance/insulin levels in many studies (7).

Reducing or controlling psychological stress is also important, as the stress hormones cortisol, glucagon, growth hormone, and epinephrine (adrenaline) are all directly antagonistic to insulin, as is an activated sympathetic nervous system (8).

With regard to diet, a lower carbohydrate intake will reduce the requirement for insulin. This will also reduce de novo lipogenesis and other metabolic activities that are driven by high insulin levels.

A lower carbohydrate diet can also clearly lower glucose levels, as is seen in a number of different studies. For instance, J. Tay et al. found:

The LC (low-carbohydrate) diet achieved greater improvements in the lipid profile, blood glucose stability, and reductions in diabetes medication requirements, suggesting an effective strategy for the optimization of T2D management. (9)

A U.K. study showed even greater benefits in Type 2 diabetes from using a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet (10). The following mean reductions were found over a period of eight months:

-

- HbA1c level reduced from 51±14 to 40±4 mmol/mol

- Weight reduction was 9kg from 100.2±16.4 to 91.0±17.1 kg

- Waist circumference decreased from 120.2±9.6 to 105.6±11.5 cm

- Systolic blood pressure fell from 148±17 to 133±15 mmHg

- Serum gamma-glutamyl transferase decreased from 75.2±54.7 to 40.6±29.2 U/L

- Total serum cholesterol decreased from 5.5±1.0 to 4.7±1.2 mmol/L

Summary

If we bring the various facts together, it is clear that obesity is not the underlying cause of Type 2 diabetes. Instead, obesity is caused by a combination of insulin resistance and raised insulin levels. Raised insulin is a key driver of energy storage, leading to obesity.

It therefore can be proposed that the likely model of obesity and diabetes is:

Raised insulin levels ± insulin resistance + excess energy → obesity + ↑insulin resistance → pre-diabetes → Type 2 diabetes

Using this model, it can be seen that consuming carbohydrates will be an important underlying cause of both obesity and Type 2 diabetes. While fats have little direct effect on insulin levels, carbohydrates (which are all converted to simple sugars before absorption) have a significant and prolonged impact on insulin levels.

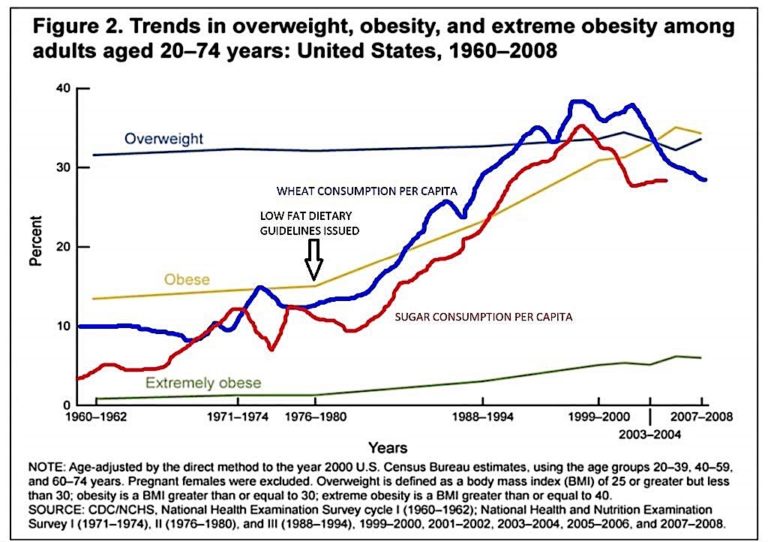

This may be why the dietary guidelines introduced in the late 1970s in the U.S. were followed by a rapid increase in both obesity and Type 2 diabetes (Figure 2 below).

One possible way to control, slow, or even reverse this trend would be to alter dietary advice to recommend lower carbohydrate intake. The benefits have been seen in a number of studies, and it would be prudent to recommend that those with Type 2 diabetes reduce carbohydrate intake rather than use agents that will raise insulin levels — including insulin itself. While these agents reduce glucose levels, they also worsen the underlying metabolic problems and may increase CV and total mortality.

Additional Reading

Malcolm Kendrick is a family practitioner working near Manchester in England. He has a special interest in cardiovascular disease, what causes it, and what may prevent it. He has written three books: The Great Cholesterol Con, Doctoring Data, and A Statin Nation. He has authored several papers in this area and lectures on the subject around the world. He also has a blog, drmalcolmkendrick.org, which stimulates lively debate on a number of different areas of medicine, mainly heart disease.

Malcolm Kendrick is a family practitioner working near Manchester in England. He has a special interest in cardiovascular disease, what causes it, and what may prevent it. He has written three books: The Great Cholesterol Con, Doctoring Data, and A Statin Nation. He has authored several papers in this area and lectures on the subject around the world. He also has a blog, drmalcolmkendrick.org, which stimulates lively debate on a number of different areas of medicine, mainly heart disease.

He is a member of THINCS (The International Network of Cholesterol Sceptics), which is a network of doctors and scientists who believe that cholesterol is not the main underlying cause of heart disease. He remains a proud Scotsman, whisky drinker, and failed fitness fanatic who loves a good scientific debate — in the bar.

Notes

- Insulin & weight gain: Does tighter control make you loosen your belt?

- Acute postchallenge hyperinsulinemia predicts weight gain: A prospective study

- Insulin therapy increases cardiovascular risk in Type 2 diabetes

- Clinical implications of the ACCORD Trial

- Reducing insulin resistance with metformin: The evidence today

- Effectiveness of metformin on weight loss in non-diabetic individuals with obesity

- Update on the effects of physical activity on insulin sensitivity in humans

- Acute psychological stress results in the rapid development of insulin resistance

- Comparison of low- and high-carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: A randomized trial

- Low carbohydrate diet to achieve weight loss and improve HbA1c in type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes: Experience from one general practice