As American waistlines have expanded over the past several decades, so has the amount of time we spend eating. In this article, we’ll examine the impact of meal frequency on our health and performance. Long gone are the days of three square meals. According to an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, people are now eating between 4.2 and 10.5 (bottom and top deciles) times per day.

The same study also identified a shift in food consumption toward snacking. In the 1970s, women aged 20-70 years consumed 82% of their calories at meal time. By 2009, this dropped to 77%. Snacking made up the difference, and similar patterns were found among men.

Appetite Drives Eating Patterns

Most people today are eating far more frequently than ever before and not as a result of careful planning. Poor food choices seem to be driving the changes in eating patterns.

In 1999, Dr. David Ludwig conducted a study Zone Diet author Dr. Barry Sears called “one of the best-designed trials I have ever seen in the last 20 years of diet research.” Twelve obese adolescents were fed two meals with either low, medium, or high glycemic index (GI) foods for breakfast and lunch. All meals contained the same number of calories (392), but the kids who ate the high and medium GI meals consumed 81% and 53% more calories, respectively, over the next five hours when placed in a simulated living room stocked with snacks and sweets. This means the high GI meals stimulated their appetites. The low GI meal was designed with Zone proportions and consisted of an egg white omelet and fruit. This more satiating meal curbed hunger.

Eating junk food leads to eating more junk food. The old Lays potato chip ad said it best: “I bet you can’t eat just one.” The type of high frequency eating you see in the top decile in the NHANES study (10.5 meals a day) is not motivated by a desire to spread calories out like an IV drip. Eating this frequently is a consequence of poor food choices that increase appetite. Eating the right food is essential to taking control of your hunger and therefore your eating pattern.

The Fundamentals of Chrononutrition

We’ll discuss three variables related to meal timing: the number of meals, the eating/fasting window, and the time of day. Meal frequency dominated the discussion until relatively recently. Some experts suggest eating many small meals spread throughout the day provides consistent energy and improves a variety of health biomarkers. Others advise eating as few as one meal a day for the same reasons. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), published by the USDA and now in its eighth edition, is the primary source of dietary information passed from the government to doctors and schools. The DGA has not yet weighed in on meal frequency. For its 2020-2025 edition, frequency of eating is a “topic under review.”

Controlling blood glucose is an important goal of any eating pattern. Hyperglycemia is associated with a variety of health conditions, including heart disease and Type 2 diabetes. Frequent small meals result in lower spikes in blood glucose. The downside is that blood glucose remains moderately elevated throughout the day, as each meal raises blood glucose above fasting levels. Less frequent, larger meals could allow blood glucose to drop to lower levels between meals but also cause higher peaks.

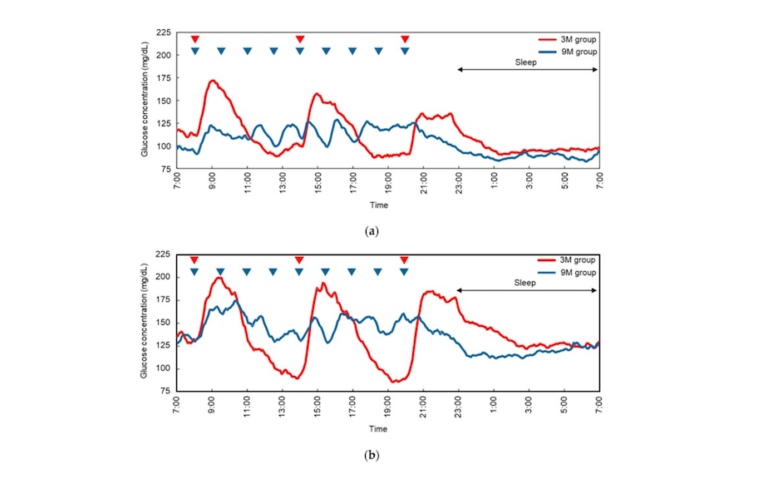

One important data point to extract from this blood glucose data is the area under the curve (AUC), or total amount of blood glucose in a day. Can this settle the argument over high or low frequency meals? A recent study tested the blood glucose response of people with normal glucose tolerance or impaired glucose tolerance. On separate days, each person would consume the same amount of food divided into either three or nine meals. Like the previous study, this study found the AUC to be insignificantly different between three or nine meals, despite the obvious differences in the blood glucose patterns.

Figure 1: Blood glucose concentrations monitored over 24 hours by continuous glucose monitors. The red lines show the 3 meal/day pattern and the blue lines show the 9 meal/day pattern. (a) Subjects with normal glucose tolerance. (b) Subjects with impaired glucose tolerance.

Another study compared three and 14 meals per day in 12 healthy men. Subjects experienced both eating patterns in a random order. They reported a lower AUC in the low frequency trial, but the difference was non-significant. The study was conducted in a respiration chamber, allowing the researchers to determine energy substrate utilization. They found no difference in carbohydrate burning. Increased fat oxidation was anticipated in the low frequency group, but this was not observed. Surprisingly, they measured a significant difference in protein oxidation (+18%) during the low frequency condition, implying the protein was used for energy rather than muscle protein synthesis. This appears to support the idea that protein should be spread throughout the day for optimal muscle growth or retention. However, the authors note, “changes in protein metabolism on whole-body level do not necessarily represent changes on muscle level.”

Meal Frequency and Weight Loss

In one study of 16 obese adults, two groups were fed the same amount of food, but each group’s food was spread out over a different number of meals; participants ate either three meals a day or three meals plus three snacks. No significant differences in weight loss, fat loss, or body mass index were observed.

Several teams have performed meta-analyses on studies of meal frequency and found inconsistent results. One study showed a slight inverse relationship between body weight and eating frequency. Confusingly, some studies showed better results with fewer meals, and others found better results with more meals. The studies were highly sensitive to confounding factors and included weak epidemiological evidence. A 2015 meta-analysis found a positive association between meal frequency and reductions in fat mass, but upon closer inspection, the reviewers noticed the outsized effect of a single study skewed the results toward this positive association.

Meal Frequency and Health

A 1989 study compared a standard three-meals-a-day pattern to a pattern involving 17 snacks per day. In a randomized crossover design, each participant experienced both protocols for two weeks each, and the meals were “metabolically identical.” Measurements were taken on day 13. During the high frequency meal phase, serum insulin levels were 27.9% lower. Reductions were seen in total cholesterol (8.5% +/- 2.5%), LDL (13.5 +/- 3.4%), and apolipoprotein B (15.1 +/- 5.7). However, it was a small, short-duration study of only seven men, so it is by no means conclusive. Furthermore, it is impractical in real life to eat 17 times a day, even if there are potential health benefits.

Another study compared eating three meals a day to eating only one. Over the course of the six-month study, participants maintained their body weight within 2 kg, so any health effects were derived from the eating pattern and not weight loss. The study design was a randomized crossover, with the 40 healthy male and female study participants experiencing both eating patterns for eight weeks each, along with an 11-week washout period in between. Every subject attended dinner at the research facility. Breakfast and lunch were also provided during the three-meal phase. The macronutrient levels of each meal were 49% carbohydrate, 36% fat, and 15% protein.

When eating one meal a day, participants experienced greater hunger and found it difficult to eat the prescribed amount of food all at once. On average, 1.4 kg of weight loss and 2.1 kg of fat loss occurred during the one-meal phase. Weight loss would likely have been greater if the participants stopped eating when they were no longer hungry. They also saw significant increases in both LDL and HDL cholesterol. When eating three meals a day, blood pressure was reduced by 6%.

A Case for Consistency

One assumption made in all these previously mentioned studies is that people in the real world eat a certain number of meals every day at the same time. This assumption likely does not match reality. Observational studies (1) have suggested irregular eating patterns could lead to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome.

A randomized controlled trial investigated meal irregularity in 2016. In the study, 11 healthy women experienced two eating patterns for two weeks each in a randomized crossover design. One eating pattern included three meals and three snacks per day, providing 70% and 30% of total calories, respectively. The other eating pattern varied the number of meals between three and nine per day. The meals provided by the researchers were 50% carbohydrate, 35% fat, and 15% protein.

The key finding of the study was a higher glucose response following some identical test meals during the irregular eating period, indicating impaired glucose control. Hunger was also reduced during the regular eating period according to surveys of the participants. Interestingly, the continuous glucose monitoring did not show a significant difference in maximum, minimum, mean, or AUC between the two eating patterns.

Prior studies by the same researchers (2) were less strictly controlled but drew similar conclusions. The participants’ meals were not provided by the researchers. Nonetheless, the researchers concluded irregular eating patterns hampered insulin sensitivity.

Where to Start

The May 2004 issue of the CrossFit Journal was dedicated to meal plans. It recommended the protocol created by Sears in the Zone Diet — three meals a day, plus two snacks. Sears describes this approach as “spread out more evenly through the day like the intravenous delivery of a cancer drug.” This is an excellent starting point, especially when combined with the Zone recommendation of 40% low glycemic carbs, 30% protein, and 30% fat at every meal.

From a baseline of five meals a day, it’s simple to add or take away meals according to your lifestyle and personal experience. The block system, also explained in the journal, offers a useful level of precision for portioning meals both in quantity and macronutrient composition.

The Zone prescription provides the tools to design a meal plan and experiment to see what works best for you.

The scientific studies on meal frequency do not offer a singular, conclusive recommendation. Over time, the American diet has shifted toward a high frequency grazing pattern. This is most likely the result of continuous hunger stimulated by poor food choices. Several controlled studies show consuming frequent, small meals delivers health benefits. However, the one-meal-a-day plan has also been shown to be effective for weight loss and metabolic health. This seeming paradox hints at a second more powerful factor, which will be discussed in the next installment.

Notes

- Eating meals irregularly: A novel environmental risk factor for the metabolic syndrome; Irregular consumption of energy intake in meals is associated with a higher cardiometabolic risk in adults of a British birth cohort

- Beneficial metabolic effects of regular meal frequency on dietary thermogenesis, insulin sensitivity, and fasting lipid profiles in healthy obese women; Decreased thermic effect of food after an irregular compared with a regular meal pattern in healthy lean women; Regular meal frequency creates more appropriate insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles compared with irregular meal frequency in healthy lean women