Observational research and small RCTs have suggested a low-carbohydrate, high-fat (LCHF) diet improves glycemic control and glycemic variability in patients with Type 1 diabetes (T1D). The existing literature, however, has been exclusively gathered in patients with long-term (≥12 years) diabetes. This case review surveys three male patients who began a LCHF diet soon after receiving a T1D diagnosis. As outlined below, all patients saw remission of T1D, defined as glycemic control without the need for exogenous (injected) insulin.

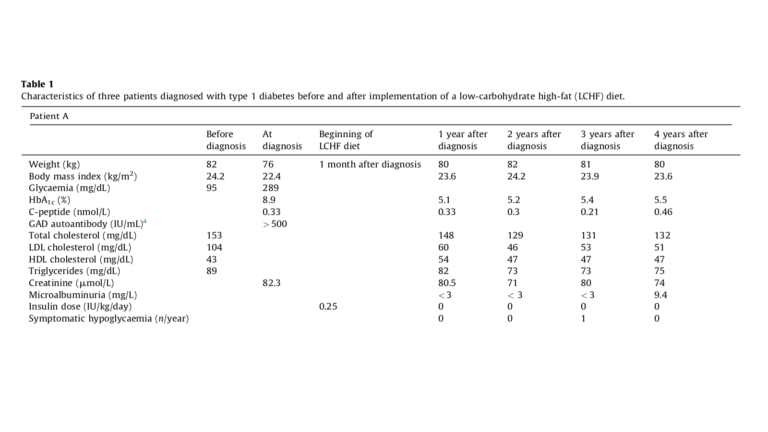

The first patient, 36 years old, presented with a plasma glucose of 289 mg/dL. He voluntarily began an LCHF diet one month after diagnosis, limiting carbohydrate intake to 50 grams per day. Fifteen days later, he was able to discontinue insulin completely — four years later, this remission was maintained with no diabetes-related complications.

The second patient, 40 years old, presented with a plasma glucose of 305 mg/dL. Like the first patient, he voluntarily initiated an LCHF diet with no more than 50 grams of carbohydrate per day two months after diagnosis. He stopped insulin therapy when he began the diet and had no further need for injected insulin except for a single infectious episode. His remission was maintained without complications for at least one year.

The third patient, 38 years old, presented with a plasma glucose of 340 mg/dL. He, like the two other patients, initially required multiple daily insulin injections to maintain glycemic control. He was instructed to initiate an LCHF diet nine months after diagnosis, restricting carbohydrate intake to 20 to 30 grams per day. He was able to discontinue insulin therapy two weeks after starting the diet but had to resume insulin therapy 18 months later.

Note that all three patients exercised one to three times per week for one to two hours each session.

These represent the first reported cases of clinical remission of T1D using an LCHF diet. The authors argue an LCHF diet rapidly leads to improved glycemic control (as evidenced by rapid reductions in HbA1c levels in all three patients); this improved glycemic control helps to preserve plasma B cell function. The patients, as evidenced by detectable C-peptide levels, retained some insulin production capacity at baseline and maintained similar levels at subsequent tests — in other words, an LCHF diet helps maintain any remaining insulin production capacity. The authors note these results may not replicate in younger or female patients, who tend to present with lower levels of insulin production at the time of Type 1 diabetes diagnosis.

This small, relatively short-term case review is insufficient to clearly show an LCHF diet provides durable resolution to T1D. Nor is it possible to generalize the effects seen in the study or any potential side effects. However, given the lack of alternative methods to prevent or even control T1D and the established safety of a properly designed LCHF diet, newly diagnosed Type 1 diabetics ought to consider carbohydrate restriction as a therapeutic option for reducing reliance on injected insulin.